Change to solid gold background

| Change to beige | Change to black | Change to white(N.B.: The black background obliterates the article at bottom of page.

This option is for IE 4+ users only; Netscape users, call a lawyer.)

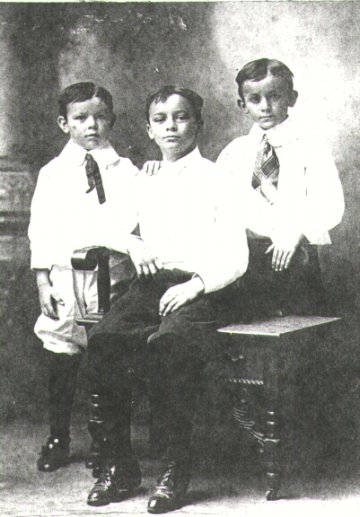

Joseph Wilbur Cash, (1900-1941), (as he was named at birth, before switching the order of his names to avoid confusion with his father, John William, in adopting initials for his eventual nom de plume), circa 1912, with younger brothers Allan, left, (1904-1994) and Henry, right, (1902-1998). Allan eventually became a successful orthodontist and settled in Charlotte where he died at 90; Henry owned and successfully managed a small dry cleaning plant in Charlotte from the early Fifties and also died there at the age of 95.

...And baby sister Bertie, ca. 1912, at about age two, (1910-1987). Bertie spent 25 years of her life as a school teacher, primarily in Lumberton and Winston-Salem, N.C. (Cash had two other sisters, each of whom died at around age two, Ruth, d. 1899, six months prior to Wilbur's birth, and Elizabeth, d. 1909, when Wilbur was nine) All of Cash's siblings shared a spirit of stubborn independence, but were less iconoclastic than Wilbur and had far more respect for organized religion than did the older brother. All shared a keen interest in political issues and would fiercely argue their positions. Bertie's political beliefs were similar to Wilbur's to whom she looked for protection and advice as a child and adolescent; Henry was more moderate and Allan tended toward conservatism, heretically changing his party affiliation after the Forties to Republican.

Father, J.W. Cash, (1872-1964), ca. 1948

Mother, Nannie Hamrick Cash, (1874-1959), ca. 1948

The Cashes were married just short of 63 years at Nannie's death. Born less than a decade after Lincoln's assassination, married just after the election of William McKinley to his first term, both lived to see John F. Kennedy's campaign for the presidency. Nannie, the church organist in her younger years, was reserved and contemplative, warm and generous in her caring for people, but could show a fierce German-Scotch-Irish mixture of stubborn determination to a cause when crossed; John, a merchant most of his life, was diligent in work from the time of his youth, could tell captivating stories of the past with a glowing grin until midnight, but would stomp his feet as Highland thunderclaps and shake from his finger Dublin lightning bolts when his wit was riled by double-talk and chicanery, be it common or political. Both were decidedly Democratic in party loyalty, but then so were most of North and South Carolina prior to the Fifties. John Cash would argue politics; Nannie would knit and occasionally take to task those she regarded as divisive. When Vice-President Richard Nixon would appear on television during the Fifties, she was heard regularly to snip: "That old lantern-jawed crook; turn him off." At Allan's considerable urging, John dropped his first Republican ballot for Ike in 1956, but returned to the fold in 1960, voting for J.F.K. Quietly religious, both were regularly church-going Baptists but of a more progressive variety of Baptist than perhaps typified the rural Carolinas in that they believed in equality of people--no better, no worse--and readily recognized that fanaticism in religion, as in anything, leads only to destruction. They were never heard to proselytize or wear their religion on their coatsleeves. By today's standards, they would not be considered Fundamentalists; just good Baptists. The year before his marriage, in 1895, John Cash had fiercely and eloquently defended the right of universal women's suffrage--not a readily accepted premise in those times--in his academy graduation debating exercises, the record of which was maintained in a ribbon-bundled sheaf of handwritten papers which he kept until his death and which still survive. Demonstrating that Wilbur Cash did not arise from an anomalous vacuum, the debate papers suggest some of the original source of Wilbur's natural ability to construct sentences with didactic fire and dialectic intensity.

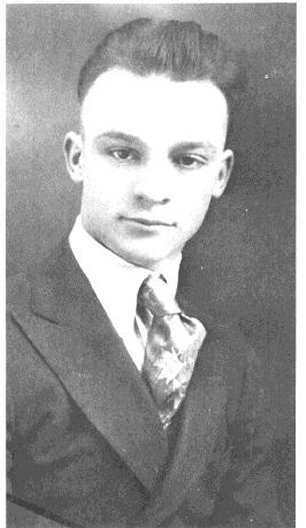

Cash, as senior in high school at Boiling Springs High, 1918. A somewhat erratic student always, Cash was the consummate daydreamer whose interest was kindled by ancient history and classical literature; not atomies and algebra.

Title page of the 1919 Bohemian, the yearbook of Wofford College in Cash's freshman year. Cash did not take to the conservative Baptist-affiliated school in South Carolina just thirty miles from his homeplace, and therefore transferred to Valparaiso in Indiana for the beginning of his sophomore year; shivering from the chilly climes near Lake Michigan, however, he returned home to begin 1920 at Wake Forest, also Baptist-affiliated, (and, at first, to Cash, "just another preacher's school") in the Raleigh, N.C. suburb of the same name. He later complained to Alfred Knopf that his father "insisted" that he first go to Wofford and then to Wake Forest, as opposed to the strictly secular U.N.C., to which Cash claimed preference. Whether this was a stretch, no one really knows. Father Cash had no objections when Henry, a mere two years younger, and Allan, four years behind, packed off to Chapel Hill (though both transferred elsewhere, but not to "preacher's schools", for graduation). Henry, in fact, went to Tulane in New Orleans, hardly a place one thinks of as a bastion of high piety. Indeed, even Bertie, the youngest, attended the secular Carolina for awhile without so much as foot-stomp from J.W. and eventually married a Carolina man with no warning from J.W. as to the perils of purgatory. Perhaps, the truth therefore is somewhere in the middle; John Cash suggesting a religious-affiliated college for the first person in his family to attend and Wilbur not truly terribly resistant to the notion, especially given his intense shyness and the far greater numbers of people attending in Chapel Hill. (To understand fully Cash's apparent adverse reaction to crowded places, read of his obvious annoyance to the traffic and people "scurrying about" in Mexico City in his "Report from Mexico", his last known formal writing, a few days before his death.)

Cash's freshman class picture at Wofford, 1919, (3rd from left on second row from bottom)

Enlarged freshman photo; Cash is second from bottom, middle

Cash's membership in "Carlisle Literary Society" at Wofford memorialized; barely discernible, Cash is 3rd row from bottom, 2nd from left.

Macabre, as only collegians can be, this crude concluding page of the 1919 Bohemian by "Splinters" is bitterly ironic, given the manner of Cash's death 22 years later. Death was on their minds, as the "Farewell" on the opposing page points out, the upper classes having been decimated by World War I; the Armistice was declared November 11, 1918. (Fudging his age, Wilbur had sought to volunteer for the Navy in 1917, but was turned down due to poor eyesight. He wound up in the Students' Army Training Corp, doing odd jobs at various Army facilities on the east coast, primarily at home in the Spartanburg cantonment, Camp Wadsworth. Perhaps, this desire to join the Navy explains in part his being taken with Delilah, by Marcus Goodrich, in 1941 as Goodrich had run away from home at 16 to join the merchant marine and eventually wound up in the Navy, fighting in both world wars. The novel begins a few months before April, 1917 and concludes with the declaration of war by the United States.)

Cash as junior at Wake Forest, from 1921 Howler yearbook; (in left frame, fourth from left--with hat in hand--amid fellow Euzelian Literary Society members; center, as "Anniversary Marshal"; right frame, main class photo, at center rear (here resembling a little the young Thomas Wolfe attending 30 miles north by northwest at Pulpit Hill). Cash had in this year given up an ever so brief "promising" career as a football player for the Demon Deacons to pursue what had fast become his first love--writing. Upon this obvious choice of Hobson, the Wake Forest student newspaper (which Cash would a year later edit) reported on October 1, 1920 that: "The gentleman states he is a poet by birth, a dreamer by nature, and a loafer by force of habit. He feared that the rough and tumble game and the violent contact with other members of his race would darken his bright, cheerful view of life. In this case, the poet claims that he would no longer be able to write, with beautiful simplicity, his touching verses on love, maidens and pastures green. Thus a good man was lost to the cause." (As quoted in W.J. Cash: A Life, Bruce Clayton, p. 29) The following spring Cash submitted his first writing to The Wake Forest Student, (perhaps intending to confirm the inditement quoted above), it being a junior's somewhat sophomoric sounding bit of soporific love-verse, simply titled, "Spring". (For all of Cash's early poetry, some of which is not in the least sophomoric, see The Poetry of W.J. Cash, accessible also from the homepage or the pop-up menu in subsequent galleries.)

(These three photos courtesy of Tim C. of the Forsyth County (N.C.) Public Library)

Upon these campestral esplanades of old Wake Forest on a given day, Cash could regularly be seen beneath a shade tree with fellow students debating the species and the world it inhabits. Given the compactness of the campus, professors would often stop by to join the discourse. Does the theory of evolution dispute or confirm the existence of God? Would it be suicidal to attempt to fly the Atlantic? Is another World War inevitable? Will Versailles hold Germany in check? Is a return to barbarism the inevitable result of civilization? What of this land from which the college campus derives, are the ghosts of the tobacco plantation which once it hosted still about in the gentle breeze? Such questions no doubt populated the discussion.

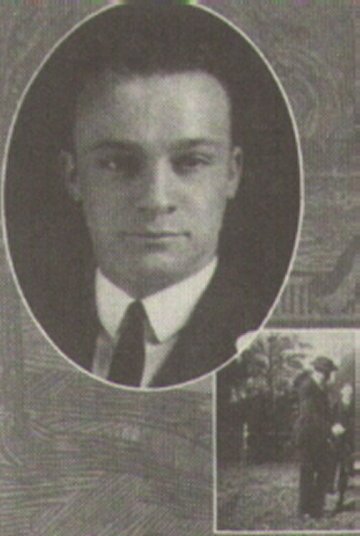

Cash as senior, 1922. (The picture on the right is of unknown significance; presumably, (though enlargement yields no conclusive proof), Cash is the stately looking gent in the fedora.) Though possessed of a wry and dry wit, only two surviving photographs, one taken by Alfred Knopf in 1939 and another for the Charlotte News in 1936, capture Cash grinning before a camera.

The inscription reads: "Age 22; Height 5'10"; Weight 158 'Go where he will, the wise man is at home.' Just because he is called 'Sleepy' does not mean that this gentleman is always in a somnolent mood, for he is usually very wide awake. 'Sleepy' served two Alma Maters before he came to Wake Forest, but having arrived, he soon distinguished himself in the literary fields of the college. As managing editor of Old Gold and Black [the Wake Forest student newspaper] and as a frequent contributor to the Student [the student literary magazine], both of prose and poetry, his work has been of high order. In the class room also 'Sleepy' has been a fair and consistent student throughout his course, ranking high in the fields of literature and history. While not the friendliest fellow in college, 'Sleepy' is important in the social life of his chums here. He will probably return next year for the study of law [as Cash did for one year before quitting, complaining that law required too much mendacity and 'was surely the most boring of professions']. Associate Editor Old Gold and Black, '20-'21; Anniversary Marshal, '21; President, Cleveland County Club, '20-'21, Member, Political Science Club, '20-'21-'22; Contributor to College Wits Number 'Judge', '21; Manager of Tennis, '21-'22; Member of 'W' Club, '21-'22; Quill Club, '21-'22; Managing Editor, Old Gold and Black, '21-'22."

![]()

May 5, 1922

An Editorial

POSSIBILITIES

By W. J. Cash

![]()

The prime target of the North Carolina fundamentalists was Wake Forest's president, Dr. William Louis Poteat, who as a biologist did not ignore Darwin's teachings and yet remained the popular and devout head of a Baptist college. Editor Cash was ever vigorous in his defense of Poteat, and in this editorial he brought heavy irony to bear against two fundamentalist "successors" to his beloved "Dr. Billy."

--Note by Joseph L. Morrison from W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet

(For three short stories and seven poems by Cash, his only published creative writing, written while a student at Wake Forest, see Poetry and Fiction, accessible from the homepage.)

SINCE some of the brethren seem so determined to transfer Dr. William Louis Poteat to the "higher field of activity and larger salary" which Editor Coffin 1 of the Raleigh Times quite sensibly suggests will be his if he is hounded away from Wake Forest because of his views on evolution, we have decided to get on the band-wagon along with the crowd, and in order to prove to the Old Guard that we have repented of the wickedness of our ways and have abandoned our heresy, we have been industriously searching the field of possibilities for a "safe and sound" successor to Dr. Poteat.

First and foremost, we wish to recommend Willie J. Bryan. Few men are so well qualified for the position. Willie belongs to the old reading and 'ritin and 'rithmetic school, and his mind is a wonderful example of what the good old days and the good old ways could produce. His brain is untainted by any of the newfangled kinds of education. He has steadfastly refused to find out anything about the theory of evolution lest he place his immortal soul in jeopardy, and as late as 1896 he had never read a book on that dreadful subject, economics, which everybody knows was invented to keep the "dere peepul" from getting Free Silver and securing all the money they wanted by the very simple device of printing it on nice white paper. Undoubtedly, he would be a great success as president of this institution. Unfortunately, however, there are about three things which make him unavailable. In the first place, Willie is reported to have designs on a seat in the world's greatest assemblage of bigots, which is sometimes called the United States Senate. Then, if he were brought here as president, the student body would undoubtedly become afflicted with the wanderlust and migrate elsewhere. Lastly, Willie hasn't yet convinced himself that the earth is flat and that the sun "do move," hence, he would not be acceptable to a number of the most pious brethren.

Wilbur Glenn Voliva 2 seems to be the next most likely prospect. Without a doubt, his views would meet with widespread approval. The delightful regulations which he imposes on the celestial-minded citizens of Zion City would exactly suit the temperaments of the Baptist young men at Wake Forest. In particular would they joy in the jailing of all culprits found smoking or loitering at soda fountains. We trust that we will not be accused of trying to amalgamate the two schools into a co-ed institution if we suggest that Comrade Voliva also be granted the presidency of Meredith.3 Surely the styles which he prescribes in Zion City would afford the modest maidens grateful relief from the shameless dress of modern society. And both youth and the maiden would rise up and call him blessed when he released their minds from the bonds of the heathenish doctrine of evolution with his wonderful theory that the earth is flat and that the sun—which is only thirty-five miles in diameter and placed at a distance of only three thousand miles—spins around the earth. But, sad to relate, Voliva probably wouldn't accept the job because he is very well satisfied with running Zion City.

And now, to

save our lives, we can't think of another possibility. What a

pity that good old Cotton Mather is dead! And, come to think of

it, we guess that most of the eligible brethren died off about

five centuries ago, unless perchance some member of the Old Guard

aspires to the position.

1 Oscar J. Coffin left the Raleigh Times in 1926 and served for the next three decades in Chapel Hill as head of the department of journalism at the University of North Carolina.

2 Unlike Bryan, Voliva was unyielding in his insistence that the earth was flat. Voliva presided over his little puritanical theocracy in Zion City, Illinois.

3 Meredith College, a Baptist college for women, in Raleigh, North Carolina.

(Notes by

Joseph L. Morrison)

![[click to go to Writing Years]](WritingYearsThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to 1941--Publication and Review]](ProphetThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to 1941--Mexico and Thereafter]](HistMarkerThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to "3-D" Panoramic Gallery Entrance]](PanScriptThumb.jpg)

![[click to go Home or Search]](Image2DistRev.jpg)

![[click to go to American Mercury Articles]](MercCoverThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to Charlotte News Articles]](CharlotteNewsHeaderThumb.jpg)

![[Go to Mind of the South Reader's Guide]](MindCoverThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to June 2, 1941 Commencement Address]](RecordLabelTumb.jpg)

![[click to go to Mary Cash article ]](Red_Clay_CoverThumb.jpg)

![[click to go to Article Re Death]](DeathProphetEmb.jpg)