Trip, Mexico City, and "Noche Triste"

Go

to Quick Navigation Bars at Bottom of Page for Other

Sections of Site |

| BOARDING a train in Charlotte on

Thursday, May 29, 1941, the Cashes began what was

ultimately their long delayed honeymoon. Jack and Mary spent two

nights at the St Charles Hotel in the city Cash had wanted to visit for ten years, New Orleans, then

traveled on to Dallas and Austin for the commencement

address on Monday evening, June 2. The university student newspaper,The Summer Texan, reported the next day, "The moon shone brightly and the tower burned orange Monday night as 1,339 students sat in front of the Main Building to receive their degrees and to be told that as Southerners they must mix clear headed common sense with their traditional courage and pride." It also added, however, that Cash's "speaking ability does not equal his writing talent".(Hear and read "The South

in a Changing World" at the audio link on the menu

bar above or at bottom of this page.)

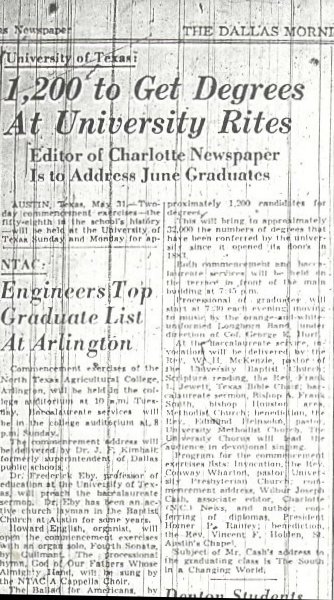

After Tuesday and Wednesday in San Antonio came the long 800 mile trek through the winding wilderness mountains to Mexico City arriving June 6th or 7th. First, a couple of "miserable" days at a widow's pensión, where they had no stove and no refrigerator and both stayed in bed from altitude acclimation. Then, a more accommodating apartment close to Chapultepec Palace off Paseo de la Reforma. They bought their own meats and vegetables with which to make "everlasting soups", as Mary called them, from a nearby open air market where Mary said the locals openly pointed and laughed at the chivalrous Cash for carrying his wife's groceries. They saw the city, the outlying Teotuhuacan pyramids, nearby Taxco, the Castle at Chapultepec, the museums, and generally enjoyed themselves for three weeks, albeit diminished part of the time by mutual attacks of the plague of all newcomers to Mexico, "Montezuma's Revenge". |

The grounds of Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City, just a short walk from the apartment rented by Wibur and Mary in mid-June. The expansive park, once home to Maximilian and Carlotta, served as a place of afternoon comfort during the last two weeks of Cash's life. (Photograph from National Geographic, August, 1940) |

On June 10, Cash wrote to his parents: Dear Mama and Dad, ...We are in a good neighborhood, a new development some two miles from the heart of the city. Chapultepec Heights and Chapultepec Castle are about three blocks away. Montezuma had his summer palace there, so did Cortez, and the palace we see is the one in which the Emperor Maximillian and the Empress Carlotta lived. General Taylor lived there for awhile too after the conquest of Mexico. [Cash refers to Zachary Taylor, said to be a distant cousin of Cash's forebears.] By the time we reached Austin I was tired and worn out, but I managed to get through the speech all right. They were very nice to us in Austin. We stopped in San Antonio for a day but we were so tired that we didn't see much of it except for the Alamo. The train jouney into Mexico was very tiring. It was supposed to last 40 hours but it actually lasted about 45. We arrived almost ready to fall over. The great altitude is very tiring at first... The first day I spent in bed because of the dizziness caused by the altitude. Up here at first all you want to do is to sleep. It is brillaintly sunny in the morning, but about three o'clock it begins to rain, not hard but steadily. Everybody knocks off about three and sleeps until five or six, then everything opens up again until nine or ten. In the mornings it is almost hot, the nights are cool and sometimes even cold. We sleep under at least one blanket all the time. The climate still bothers us somewhat, makes us awfully tired by midday, but we are beginning to adjust to it now. And both of us like Mexico (they never call it anything but that here) a great deal. The city is immensely beautiful and colorful. And the Indians in particular are interesting. We have a little servant in the apartment house (not our private servant but that of the whole house), who works for nearly nothing and who is charming in her eagerness to please. The Indians are the Negroes of Mexico, but they have it even harder than our Negroes, and they are more prepossessing... We have seen so much that I shan't even try to describe it now. But we want you to know that we are all right and comfortable. And don't worry. Mexico is a civilized if a somewhat backward country, and we have encountered nothing but the kindest treatment. Wilbur and Mary This is the last letter known to have been written by Cash. (Except for the second, third and last paragraphs, this fragment appeared in Southern Prophet, pp. 126-127.) The parenthetical clarification that the young Indian girl was not the personal servant of Mary and Wilbur underscores the notion that the elder Cashes never hired house help, probably believing it to be atavistic. For the full online text of this letter and photo-views of the original, see The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library. |

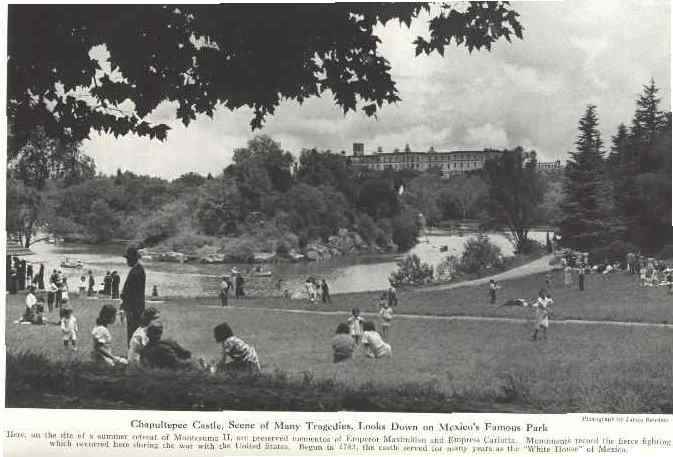

The Palace of the Fine Arts, also near the Cashes' apartment, stands then as now at the center of Mexico's busy central plaza on the edge of Chapultepec Park; the stubby building to the right, La Nacional, was then the tallest "skyscraper" in Mexico. The then-new Hotel La Reforma, razed in the early 1980's, was nearby, probably visible in the upper portion of this photograph. (Photograph, National Geographic, August, 1940) And as Palacio de Bellas Artes appears today... |

During June, Wilbur set down the outline for a never-published article which appears below. He had intended to offer it for syndication but was dead before he ever could properly place on it the finishing touches. It extends, still somewhat disjointedly, his more formalized initial impressions of Mexico, its people and its political climate. It is the last formal writing Cash ever did. Was this a man likely to be suffering paranoid delusions of Nazi agents following him a week later? Suit yourself. (This article appears in The Reader section of W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet, by Joseph L. Morrison, Knopf, 1967.) As perhaps an interesting historical footnote to this article, Popocatepetl had its most severe stirring from its long sleepy slumber in 1,200 years on December 18, 2000, the same day it might be noted for posterity, that the election for President of the United States for 2000, was decided, at least as the quaint convention of the electoral college would have it, though the popular will of the people of the United States was quite a bit different. And one of Popo's notable eruptions also occurred in the year Cortez invaded Mexico, 1519, seeming to Montezuma as a descendent of the god of light, Quetzalcoatl, but rather turning out in the following year to resemble more the god of darkness, Tezcatlipoca, eating the hearts out of Montezuma and his followers. And as to the policemen's whistles of which Cash makes mention, as did Mary in her 1967 account, see for higher learning, "Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee [of Congress] to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Alabama, Volume III," Government Printing Office, Washington, 1872. (Full testimony begins at page 1405 of linked text, to which the reader will have to navigate backwards from the above-linked page 1487.) By W. J. Cash Mexico, D.F., it strikes me as a newcomer, is probably the earth's noisiest city per square inch. All night it roars with the most ominous roar I have ever heard—a roar that still is a long menacing growl away out on the Calle Rio de la Plata where I live, and which is somehow like those somber clouds which hang over Chapultepec, visible from my window. The growl is punctuated and made complete in its effect by the almost constant shrilling of the lonely policemen's whistles, whose eerie sound must certainly date from the Aztec period. It is overfanciful to say that, awakening suddenly, one can imagine uneasily that old Popocatepetl has stirred at last from his long slumber and is pouring fire and doom down upon the town, or that Huitzilopochtli, the ancient war god, is again on his throne in the great oppressive pile on the Zocalo, with the priests tearing out the smoking hearts of 70,ooo captives in his honor. But, to the North American mind, Mexico is an overfanciful city. By day downtown, one is driven often to seek comparative sanctuary in the Alameda with its muffling screen of old trees. The explanation seems simple. The Mexican obviously delights in noise with childlike joy. With excuse or without he sounds his horn at least once every thirty seconds. And if he hasn't a horn, he makes up for the lack by the use of his powerful, if most usually tubercular, lungs. Nearly everything on wheels, indeed, does have a horn—busses and streetcars as well as automobiles. And no piddling, half-hearted horns but mighty deep-throated ones, fit to serve battle fleets in the fog. Contrary to the popular opinion in the United States—to my own, until I came here—the city swarms with automobiles, nearly all of United States make and nearly all relatively new. I have seen fewer jalopies here than anywhere I have been in the last five years. Moreover, the cars run generally to the more expensive makes. The taximen stick largely to the cheaper three, but with private owners Buick seems most popular, with the larger Packards and Cadillacs visible in great numbers. The Mexican, I hear, still holds to the notion that a long black automobile is the best symbol of rank and power, and promptly buys one the moment he can. Downtown there are a few traffic lights, but for the rest the cars dash about on their own at breakneck speeds. The drivers are the most skillful I have seen—else the whole automobile population would at once be dead. For the pedestrian, crossing a street is an enterprise to be undertaken only after extreme unction. But the little Indians glide nonchalantly among the speeding machines with cat-foot agility, remaining miraculously unhurt. More wonderful than the noise and the traffic is the building activity. I have never seen anything like it. Even in Florida in the 1920'S the effect was less spectacular, since it was spread over a greater territory. One gets the impression that every other street is being torn up to be rebuilt. And downtown the city gives exactly the effect which I imagine is made by a city which has been heavily bombed and is in process of reconstruction. The unfinished gridiron building at Juarez and Reforma, with its front knifed away and its walls cracked and seamed (apparently no effort has yet been made to restore it) by the earthquake of last April, adds verisimilitude to the effect. And for block after block the scene is unbrokenly one of old town houses coming down and huge new skyscrapers going up—no flimsy, goods-box skyscrapers like those of much of the American hinterland, but massive and impressive structures, most usually in the pyramid style so often seen in New York, though the influence here seems to be that of Mexico's past. Nor is it only the downtown district. From my window I can see a dozen apartment houses rising, all in the modern functional manner of which Mexico has become the chief exponent. I can walk fifty feet around the corner and see a dozen more. And throughout the whole so-called "river area" of the city (stretching along the west side of the Paseo de la Reforma from, roughly, the neighborhood opposite the American Embassy to the Heights of Chapultepec), much the same thing is going forward, as also in the Colonia de Valle, the fashionable Heights of Chapultepec, etc. Perhaps the government employment programs have something to do with all this building activity. But the main occasion for it, I am told, is that the former owners of the haciendas have finally about given up hope of getting their government-confiscated lands restored and are pouring into the city to invest their liquid funds in real estate holdings, at once to insure their incomes and in the hope of avoiding further confiscation. About politics I am much too new here to risk any opinion. I can report, however, that in a single day I have had two diametrically opposed assurances. One came from a man in the employ of the United States, who for many years has regularly traveled over all Mexico. There is no doubt at all, he told me, that Mexico is solidly lined up in support of the United States foreign policy, and that not only the government but the great majority of the people will back Washington to the hilt if war comes. The Indians out in the country, he admitted, are concerned only with their own affairs and don't much care about the war one way or the other, when they know about it—which isn't often. And the towns swarm with Nazi and Communist agents. But these, he said, have now been decisively defeated and are reduced to gnawing their nails in rage, while the great body of the people who are concerned with political matters are lined up behind the government. The other assurance came from a studious young woman from the western United States who has been down here for two years and who is an intimate of a number of Mexican journalists of decided anti-Nazi sympathies. According to her report, the Good Neighbor policy has been successful only in superficial ways. Even in the government, she alleged, only the foreign minister and the education minister are really wholehearted in their commitments to Washington. Furthermore, she said, the government is far from really enjoying the support of a majority of the people, won the last election only by fraud and force, and the nation is actually divided about fifty-fifty between pro-Americans and pro-Nazis. After all, they say ( according to her ), it is the Gringo and the British who have done everything evil to us in the past. Sure, probably the only reason the German didn't do it was that he had no chance. Even so . . . I offer these opinions entirely without prejudice, having, as I say, formed none of my own. Viewpoint:

A friend of ours, another U.S. employee, just missed

trouble the other evening. Invited out to make a night of

it by two young Mexican officers, he had regretfully to

decline because of a previous engagement. The two

officers went on anyway, and in the course of their

celebration got into a fight with the police, were

finally jailed after a long battle when the cops'

whistles brought reinforcements to their aid. Next day,

when the judge began to lecture the officers, still

somewhat in their cups, on their duty toward the civil

authority, they attacked him also. Now, of course, they

are in trouble up to their necks. A captain in the army

shook his head sadly when he talked to our friend about

it. It was, he avowed with choler, a disgrace to the army.

Yes, a burning disgrace. Any army officer should know

that the way to deal with cops was to sock them quick and

hard and then get away fast before they had time to bring

up aid. For a photo of the original manuscript of this article see The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library |

Advertisement for Hotel Reforma in Mexico City from National Geographic, August, 1941: "Mexican hospitality at its best. On the beautiful Paseo de la Reforma. Distinguished atmosphere. Superb appointments. Singles from $3." Three dollars was considered a high price to pay in those days for a single hotel room, especially in Mexico; this was the same cost, for instance, as a single room in the Gramercy Park or the Vanderbilt in New York City. The fact that on the last evening of his life Cash suddenly and secretly fled the Geneve within an hour after checking in and then obtained a room at La Reforma thus does not fit at all Cash's lifelong parsimony--resulting for instance in an angry reaction from Cash when Mary bought an extra copy of the New Orleans Picayune for a dime during the trip to Mexico. Subsequent history shows that the Reforma was a favorite hostel for Nazi agents in Mexico City, notably Hermann Goering protege and one of the the Nazi's top experts on Latin American economic penetration, Joachim Hertslet of the Reich Foreign Economics Ministry, and his associate and Texas-Louisiana millionaire and Nazi oil supplier, William Rhodes Davis, Abwehr agent number C-80. The two had repeated meetings with Germany's ambassador to Mexico, Baron Rudt, in the Reforma's presidential suite throughout 1939 and into early 1940. Davis used the hotel whenever he went to Mexico. Davis went to Mexico City in mid-June, 1941 to meet with Mexican government officials in an effort to establish a bank in Mexico which would have, if implemented, ultimately enabled re-funding of the financially depleted Nazi espionage activities.(See, e.g., Mystery Man, by Dale Harrington, Brassey's, 1999, pp. 63, 80-81, 126, 184; Hitler's Undercover War, by William Breuer, St. Martin's Press, 1989) Cash had editorialized on Davis as late as January 7 and 10, 1941, calling him first a "prize sucker", then a traitor for his trades--in mercury. (See "Bad Defense" and "A Buyer", Charlotte News) Alchemy may not turn mercury to gold, but may yet yield truth from untruth, reality from unreality. |

| SO came the perplexing night of June 30,

"noche triste" in Mexican lore, the anniversary

of the massacre by Cortez's men of Montezuma and his

followers in the year 1520. Cash

appeared to Mary to have a mental break, claiming to her

that he was being followed by Nazi agents who wanted to

murder him. He waved a butcher knife around saying he was

ready for them.

After calming, he asked Mary to read from Ecclesiastes. Next morning, he agreed to Mary's request that he see a physician; but made her stipulate that they would then find a new place to live where they could not be traced by the Nazis. He received a vitamin B1 shot from a doctor in the early afternoon and then cryptically stated to Mary, "I've been poisoned." He locked their papers and passports in a safe deposit box and they set off in a cab looking for a suitable hotel. After stopping at four, he settled on the Geneve. (It turns out that this was the hotel which was home at least through the summer of 1940 to the chief Nazi sabotage expert on the North American continent, one Karl Rekowski. [The Game of Foxes, by Ladislas Farago, McKay, 1971, pp. 306-308])

Hotel Geneve, Mexico, D.F. Arriving in the hotel room, Cash was still upset, claiming the Nazis were close; Mary decided to summon an Associated Press reporter, with whom they had struck up an acquaintance, in the hope of calming her husband. According to Mary, Cash would not let her use the phone in the room as it might be tapped; for some reason, rather than using the lobby phone, Mary left the hotel for about an hour. When she returned Cash was gone. She eventually summoned the police and after calling several hotels, they found him at around 10:00 p.m., registered at the Reforma. Mary and the police went to the hotel, obtained the keys to the room, opened the door and saw Wilbur hanging by his own necktie from a hook on an open bathroom door. There was no note and no prop beneath or near him. He had been dead for several hours. Mary looked at the scene only for an instant and turned away. Against the wishes of Cash's parents, she had Cash's remains cremated for the stated reason that she could not bear the long train ride back to North Carolina to carry his body. (See telegram and letter from Josephus Daniels to Cash's parents on July 2-3, 1941 indicating the choice to cremate, and a telegram from Mary to Cash's parents, dated July 2, 1941 at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library. Note that there is no time manifest on the July 2 telegram from Daniels to the Cashes and that Daniels bothered to quote the telegram in the obviously slower letter sent the next day. Compare it to the other telegram of condolence from Daniels to the Cashes, marked as sent 1:10 p.m., July 2. In 1966, Mary confessed to Joseph Morrison that she had received the telegram from the Cashes protesting cremation before the cremation, viz: After three tumultuous days during which Mary was aided by Josephus Daniels and his wife in trying to gain her passage out of the country, including, according to Mary, a phone call by Daniels to F.D.R. on July 4 to expedite matters, she boarded a TWA flight on July 5 with an urn full of ashes and made the lonely trip back to Charlotte. (Letter from Mary to Morrison, August, 20, 1964, p. 2, Morrison Papers, for comment on call to F.D.R.) The Guggenheim Foundation paid for Mary's return flight. No one ever had the heart to ask Mary why the Guggenheim Foundation would not have also paid the plane fare for Wilbur's full remains. Undoubtedly, and very likely for good reason, she was gently pressured by Josephus Daniels to cooperate. |

| THE Cashes never blamed Mary for her

judgment but obviously it deprived them of any hope of a

proper autopsy and an objective determination of the

cause of death. In times where nearly half the population of Mexico had pro-Nazi leanings as evidenced by the 40% vote the previous summer for the fascist-backed presidential candidate, for anyone today or then to believe that the Mexico City Police Department would have provided a thorough, unbiased investigation into the death of an American journalist who could easily be passed off as a deranged suicide is to engage in fantasy beyond belief. Indeed, after a deal made with the Texas-Louisiana oil man, William Rhodes Davis, the Mexican government had shipped massive quantities of expropriated American and British oil to the Nazis from 1938 until the invasion of Poland in 1939 and would have continued to do so but for a British blockade preventing shipments into Germany. In return, Mexico received industrial goods from Germany. The Mexican government was trying to walk a tight rope between not overly offending the United States, its geographical ally, and also not offending Germany, its historical economic ally. Meanwhile, the United States was trying not to do anything which would inexorably bring it into the War. The Cashes realized that just a week earlier the Nazi war machine had invaded Russia and was moving steadily toward Stalingrad. There was heavy debate in Congress that very week over whether the United States should now enter the War. Any slight fuse ignited then and there could create problems--far beyond Shelby. If Mexico was crawling with Nazi agents who could kill American journalists at will, what next? Mr. Daniels was a North Carolina legend and a friend and Mr. Roosevelt still called Daniels, his old Navy Department boss, "Chief". The Cashes would have to abide in faith for the sake of more important matters. Cash was buried in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby on Monday, July 7. Nothing remains of his

intended novel, to have been about a wealthy South

Carolina cotton family, centering on the newest

generation represented by Andrew Bates, born 1900.

|

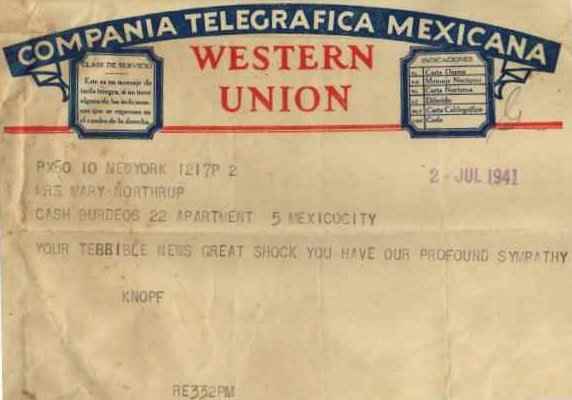

Telegram from Knopf sent at 12:17 p.m. July 2, 1941 expressing sympathy to Mary. Indicative of how fast word had spread of Cash's death, this telegram was sent from New York just twelve hours after the discovery of Cash's body.

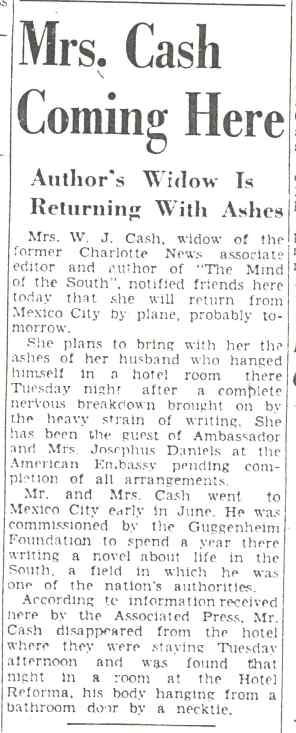

Below, the front page of The Charlotte News announced the tragedy without any question of the official report from Mexico. (For some contrast in the way it was reported across town at The Charlotte Observer, see Observer story image from within the Panoramic Gallery, 1941--Afterword (link to Pan Gallery at bottom of this page). Also read Observer a transcription of the original editorial of the same date at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library.) |

|

--from The Present Crisis, by James Russell Lowell, ca. 1865*

![]()

Upon Cash's simple marble grave marker in Sunset Cemetery his father chose to have carved the words from the verse above, and thus it does repose, "...Behind the dim unknown standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above His own." |

If you look closely at the upper right corner of the stone you will see evidence of souvenir hunters having chipped off small pieces over the years. |

Headstone of W. J. Cash and Cash Family marker. |

Letter of condolence from Homer P. Rainey, president of the University of Texas, who had invited Cash as the commencement speaker. |

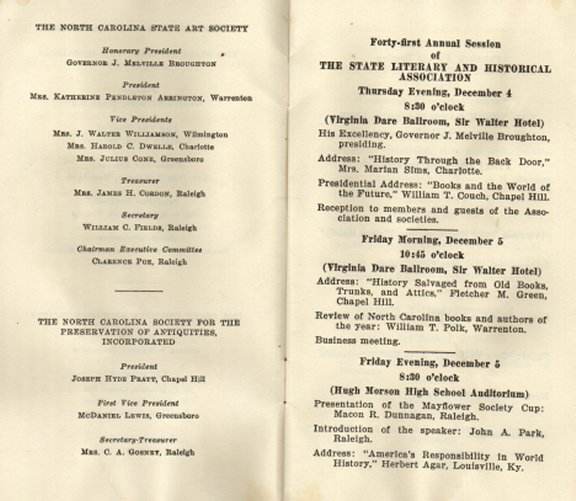

The Mayflower Literary Society Cup presented posthumously to W.J. Cash for The Mind of the South on Friday, December 5, 1941 by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association in Raleigh. John W. Cash and Mary Cash accepted the cup together. Josephus Daniels, having retired as Ambassador to Mexico in October, was present for the ceremonies. The featured speaker was to be Herbert Agar on "America's Responsibility in World History". (See Programme below.) But Professor Agar's plane was grounded because of inclimate weather and Josephus Daniels filled his place, speaking on "Mexico and the Good Neighbor Policy". Of the award, he said, "I am greatly gratified that the cup goes in recognition of the genius and ability of W. J. Cash, a brother journalist of Charlotte, given posthumously to his wife, also a journalist.... In life he brought honor to the State he loved. And tonight...the award of the Cup to the author of The Mind of the South assures him a lasting place in North Carolina's 'Hall of Fame'." (See full text of Daniels' speech at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library.) Some 41 hours later, at precisely 7:50 a.m. Hawaii time, 1:20 p.m. Eastern War Time, an event would take place which would at long last bring the United States into the War against the "little rat-like man leaning on the balustrade". As the attack was being waged, recording engineers at the University of Texas were busy transferring Cash's June 2 graduation address to phonograph records, mailed to Mary on December 13, 1941. |

Nell Battle Lewis's piece of December 14, 1941, praising the award of the Mayflower Cup to Cash. |

Letter from Alfred Knopf to J.W. Cash, indicating he would inform the elder Cash of the book's sales from time to time. After some consideration, the Cashes allowed Mary to retain rights to the book as widow; she eventually sold the rights to Knopf for $100 in the late Sixties. |

Letter from Mary to J.W. Cash dated January 13, 1942. Eventually Mary joined the W.A.C.s and after the War met an Army Major whom she married. After only two years of marriage, in the early 50's, she was widowed a second time and never remarried. She lived the remainder of her days in Silver Spring, Maryland and died there of cancer on September 4, 1980. In accord with her request, her remains were cremated and scattered from an airplane over her alma mater in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Hollins College in Virginia. |

Posing beside the Mayflower Cup on December 30, 1956, Nannie and J.W. celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary. They would have two more before Nannie's death in August, 1959. (Photo from the Shelby Star) Both went to their graves firmly believing that their son was murdered in Mexico by Nazi agents and/or Klan sympathizers. From 1942 until Nannie's death, they lived on Sumter Street in Shelby, just behind the large home occupied by Governor and Senator Clyde R. Hoey. As a result, many luminaries, even including President Roosevelt on one occasion, would visit, more or less, right in the Cashes's own backyard. Hoey, succeeded in the Senate at his death by Sam J. Ervin, was buried in 1954 thirteen feet from the grave of W. J. Cash. |

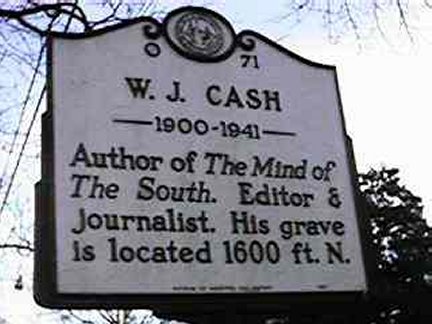

State of North Carolina historical marker, corner of Marion and Martin Streets, Shelby. |

THE BUDDHA Now,

Old Teacher of India's brown-skinned brood, --From The Wake Forest Student, Vol. XLII, January, 1923 |

* Special thanks to John C. for helping this site locate the Lowell poem

Oil rendering of Cash by J. Wm. Kinsel of Stumptown Landing, S.C.