Go

to Quick Navigation Bars at Bottom of Page for Other

Sections of Site |

PROHIBITION, DEPRESSION, WAR

THE MERCURY, THE NEWS, THE MIND OF THE SOUTH

1923-1940 - THE WRITING YEARS

"In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand: for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good. Truly the light is sweet, and a pleasant thing it is to behold the sun: But if a man live many years, and rejoice in them all; yet let him remember the days of darkness; for they shall be many. All that cometh is vanity."--Ecclesiastes

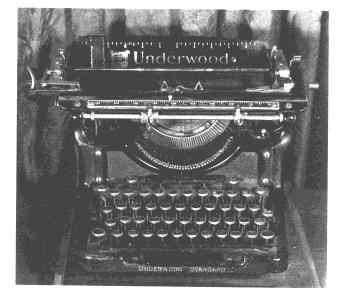

W.J.Cash's well-pressed Underwood typewriter on which he composed The Mind of the South during the 1930's. He bought a new portable to take to Mexico as the bulk of the Underwood prevented easy transport; Mary reported that he regularly cursed the new apparatus for its closely set keys. (After the death of Cash's parents, the Underwood was in the possession of Cash's sister Bertie Elkins and her family from 1960 through 1991, when the Elkins family donated it to the Wake Forest University Library Historical Collection.)

The desk where the Underwood once actively reposed awaiting its owner's daily erratic punch. (The original natural finish of the maple has long ago been covered to refurbish years of lost lustre.)

The frontispiece of the last of three Bibles given to Wilbur by his parents. After his adolescence, rarely a church-goer, he reported in the Thirties that nevertheless he had read the Bible "lid to lid". It is believed that he carried this particular Bible with him to Mexico and that it was the one out of which he asked Mary to read from his favorite book therein, Ecclesiastes, on the night before his death.

Twelve miles of lonely tracks separate Shelby from Boiling Springs. For three months in the fall of 1928, Cash walked and thumbed his way along these tracks and its adjacent roadway to reach this Shelby end, a couple of blocks from 103 West Marion Street, the office of The Cleveland Press where he held forth as editor of the new little weekly paper--which foundered after five months of existence, two months after Cash left on November 16 to return to Boiling Springs. As he had while assistant editor of The Charlotte News during the latter part of 1927 through May, 1928, Cash turned out more of his "Moving Row" columns, consistently hammering the evils of the Klan, their religious and racial bigotry, and attacks on freedom of speech, the press, and freedom in general--especially prevalent at this time in the election between Herbert Hoover and the Catholic Al Smith. Cash's bitterly partisan inveighing against this intolerance gave way to another bout with neurasthenia and he was advised by his physician to quit. This seemingly anti-climactic event, however, proved fateful for it was a few months later, in May, 1929, that he would have acceptance of his first articles from H.L.Mencken and The American Mercury, articles from which the book would eventually develop. (For more on this short phase of Cash's life, see W.J. Cash: A Life, Chapter 4, "Editing a Country Newspaper", by Bruce Clayton, L.S.U. Press, 1991.)

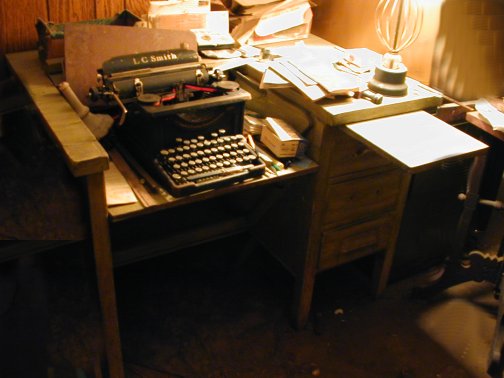

The side of the tiny post office building at 145 Main Street in Boiling Springs across the street from Gardner-Webb College where Cash wrote his first four articles for The American Mercury and began work in 1930 on the manuscript for The Mind of the South. During large parts of 1929 through 1932, Cash would walk the few blocks from his parents' home to the post office each day and, with the permission of his Aunt Bertha Hamrick, town postmaster, read and type away beneath the spare light of a single bulb until late hours of the night in the cubbyhole room at the back, looking out over the town cemetery where generations of his mother's relatives lay buried. Though the little building still exists as of March, 1999 and until recently was occupied by a dry cleaner, it has sadly fallen into such disrepair that it appears slated for the wrecking ball, a hearing having been held in September, 1998 to determine its fate.

Main Street side of old Boiling Springs post office

Views of the two Shelby houses in which Cash wrote a little more than two-thirds of The Mind of the South between late 1932 and October, 1937, as well as the last four Mercury articles in 1933 through 1935 and his freelance News editorials and book reviews from late 1935 through late 1937. The top photo shows the house on Belvedere Avenue and the lower, the still extant little house at 203 North Morgan Street. Cash's room in the latter house was behind the third window from the front on the right side. As with many elderly people, the Depression had financially depleted the Cashes and John was forced to rent out the handsome turn-of-the-century Victorian in Boiling Springs in late 1932 to make ends meet while he rented first the stately house on Belvedere and then, in early 1936, the much smaller brick cottage on Morgan. (Eventually, with Wilbur as co-signatory, he had enough gathered to purchase the Morgan Street house in 1940.) Suggesting the move also was the fact that the household was reduced in size by 1932 with the graduation from college of Henry and Alan in the mid-Twenties and Bertie's graduation that spring.

Punctuated by a year in Chicago, a few months spent in Charlotte while working for The News in 1926-27, a three month bicycle tour of Europe in summer, 1927, another six month stint with The News in 1927-28, and his editorship of The Cleveland Press in Shelby in fall, 1928, Cash lived at home from 1925. Continuing to be financially depleted and suffering periodic bouts with neurasthenia, the restive Sleepy made the move with his parents to Shelby and continued there until his move to Charlotte in fall, 1937 to join the News full-time as associate editor.

Thus, it was in these two houses in Shelby that the first serious writing on The Mind of the South took place. Cash had written a version of the manuscript while still in Boiling Springs but destroyed it as sounding too much of a dry academician's monograph, replete with footnotes, a device Cash considered to be signal of a poor writer.

And it was in the house on Morgan Street in the early morning hours of July 2, 1941 that John and Nannie Cash first received the news of Wilbur's death. Mary had called Cash's friend Pete McKnight at the News and McKnight had called Bertie and Charles in Lumberton who then broke the sad news to Shelby. Life would never quite be the same again for the elder Cashes and they moved from this house in 1942, building another home four blocks to the west on Sumter Street where life would remain largely at rest, if sometimes punctuated by health problems, in their last score of years.

The clock tower of the old Cleveland County Courthouse in Shelby (now the county historical museum) below which stands the ubiquitous Southern symbol of tradition, a copper instilled image of a Confederate soldier, (see picture below), and also below which Cash, the local railer at those traditions, would spend many early to mid-Thirties spring, summer, and fall afternoons simply lolling about the square observing, listening, occasionally exchanging community scuttlebutt--but mainly just thinking it all through to imprint its inner recesses properly through the typewriter ribbon onto paper. If one sits a bit in this square after having read Cash, one gets the distinct impression of a view from this rather tranquil place in many parts of The Mind of the South, as well as in many of his articles on the South, such as when he writes to us in late 1933 of the declining state of western civilization in the American Mercury article, "Holy Men Muff a Chance".

The inscription embossed at the foot of the Confederate perhaps speaks an unwitting tome of a violent and tragic underbelly of the South very much still alive in Cash's day but disappearing slowly with each generation passing further from the pastoral fantasy which Cloud-Cuckoo Land produced of itself from an acrid combination of tears and animus...

Bookish looking Cash circa 1930; this photograph accompanied American Mercury biographical note in the October, 1932 issue containing Cash's fourth piece, "Paladin of the Drys"

Just five years later in 1935, Cash shows the effects of intensive writing and research on de minimis finances amidst Depression conditions.

![]()

Baltimore Evening Sun -- August 29, 1935

![]()

NORTH CAROLINA FACES THE FACTS

BY W. J. CASH

In this article on Negro lynching, Cash unswervingly went to the heart of the matter: that lynching had the covert approval of the majority of Southern whites, including the "best people." Although he did not support the federal anti-lynching laws proposed during the 1930's, arguing that in the charged emotional atmosphere of the South they would do more harm than good, Cash later drove home his indictment of the South's "best people" in The Mind of the South manuscript.

--Note by Joseph L. Morrison from W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet

As a Southerner and a North Carolinian, I think I am able to discover one very hopeful circumstance in the case of the lynching of a raving-mad black man at Louisburg, in Franklin county, North Carolina, which took place recently. It is this: that there is beginning to appear in the South—in North Carolina, anyhow—some willingness to approach the problem of lynching in a realistic spirit.

It has long been the custom, of course, for the chief newspapers in the Southern country to decry lynching as an inexcusable barbarity. But it has also been the custom to say that, after all, the South as such was not to be held responsible, that the people who actually lynched were only a handful of degraded poor-whites, that public opinion in general was not in favor of it, and that the "best people" in particular were dead set against it.

The claim was never true, obviously. Take this case at Louisburg for instance. A mob of twenty-five men without masks or disguises took the victim from the Sheriff of Franklin county and five of his deputies in broad day.

Not a blow was struck, not a gun was drawn. The killers simply said they wanted the man, and the Sheriff accommodatingly handed him over. Afterward, in the court of inquiry convoked by Governor Ehringhaus, the Sheriff and his deputies were seized with complete amnesia. They could not recall the makes of the automobiles used by the killers, they could not recall whether or not these automobiles had license plates, and they could not remember that there was a single face in all the twenty-five that they had ever seen before. How absurd that is will be manifest to anybody who knows the rural South, and knows that, in such a county as Franklin, it is always impossible to get together so many as twelve men without the Sheriff and his deputies being able to name at least eleven of them.

The fact is overwhelmingly plain. The hands which actually manipulated rope and trigger at Louisburg may very well have been those of degraded poor-whites. The hands which actually manipulate rope and trigger—or kerosene can and brand—in Southern lynchings generally are very often those of degraded poor-whites, though not always. But the force which really lynched at Louisburg—the force which really lynches everywhere in the South—was and is the force of public opinion.

And when one says public opinion, one shifts the ultimate responsibility straight back upon the "best people"— the ruling class. For these people everywhere very largely determine public opinion, of course. And they do so with particular effectiveness in the South—for two reasons. One of these is that, under the Southern political and economic system, social control is remarkably concentrated in the hands of a relatively small group of landowners, time-merchants, bankers, and the chief lawyers of the county seat. The other reason is historical—that, for seventy-five years, the South, high and low, rich and poor, has been absorbed with almost unparalleled completeness in a single issue; that, as a result of that long obsession, the masses stand to the master class very much as, say, the veterans of Austerlitz and Marengo stood to Bonaparte and his marshals: that they trust them with a marvelous trust, are greatly dependent on their favor for a good opinion of themselves, and look to them always for instruction as to what to think and believe and do.

I suggest nothing so nonsensical as that all Southerners favor lynching, surely. Hundreds of men in North Carolina, thousands in the South, hate it passionately. None the less, the great body of the master class does favor it. On no other hypothesis can we explain the fact that the police officers— hardboiled, small-time politicians, with a very accurate sense of the realities of their world—almost invariably behave as the Franklin county officers behaved.

But the encouraging thing about this case is that this time there were no excuses. This time not a single newspaper in North Carolina, so far as I know—certainly, none of any importance—laid the blame at the door of the poor-whites, not one said that we must be careful not to charge the crime to "the good people of the State."

On the contrary, virtually all of them spoke out with more vigor and more anger than they have ever shown before. And though many of them contented themselves with a pointless lambasting of the Franklin officers, some of them went further and more or less explicitly laid the blame in the quarter where it belongs. It was so with the three chief papers of more or less Liberal leanings—with the Greensboro Daily News, the News and Observer of Raleigh, and the Charlotte News. And, what is much more significant, it was true with the Charlotte Observer.

The most powerful journal in the State, this last is immensely conservative, and its policy has always been one uncompromising Southern apology. But this time it not only dispensed with apologetics, it even led the charge upon the fact. Carrying a series of sharp editorials, all pointing more or less definitely toward the truth, it crowned its efforts by printing an editorial article, written by LeGette Blythe, an able member of the staff, which unequivocally proclaimed, first, that it is the "good people" of Franklin county who are to blame for the Louisburg affair; secondly, that these "good people" are exactly of a piece in their attitude with the "good people" of North Carolina and the South generally; and thirdly, that it is high time to face the facts and act upon them.

I have no illusions. Knowing the tremendous compulsives back of the will to lynching in high and low, I think it is going to be a long time yet before the practice is effectually stamped out in the South. Nevertheless, here is plainly a sound beginning at last. Here is unmistakable evidence of a rising tendency—in North Carolina at least—to lay aside the old ferocious Southern sensitiveness and stubborn blindness, and confront the issue. And so here is ground for solid hope.

This picture, finding Cash with a rare smile, appeared in the Charlotte News March 8, 1936 to announce the signing of a contract with Knopf for publication of The Mind of the South. The Knopfs had first proposed the book to Cash in 1929; but they were not sufficiently comfortable with a contractual arrangement until he had shown them substantial work product. By early 1936, with 300 manuscript pages in hand and the promise of Cash of the finished work by July 15, Blanche Knopf is quoted as saying that the book is "the best picture of the South I have ever seen". Such is ironic as much of what Mrs. Knopf had then seen never made it to print; Cash would revise, delay, and frustrate the Knopfs for four more years until late July, 1940 before finally delivering the last of the completed 800 page manuscript. Indeed, by early 1936, he had really only just begun to write the final draft of the book, though he had completed reams of solid work suitable for publication in the six years prior to that--but not suitable to Cash's perfectionist eye. Having finished one version in 1933, he promptly threw it in the fireplace and started over. His sister would often comment that it was this tendency toward precision which was both his greatest strength and his greatest weakness. She was not alone in the observation. Cash called himself "the laziest man alive" and others about town agreed with this self-deprecating assessment; but those who knew the situation closely appreciated the enormity of the task and the need to read scores of books and monographs and search dusty newspaper files and genealogical records preparatory to writing on such a deliberately obscured matter as the cultural mind of the nation's least fathomable region. The caption above describes Cash as a "former member" of the News staff and a regular contributor to the book page. Cash had served a brief stint as an assistant editor in 1928 before succumbing to neurasthenic problems forcing him back home to Boiling Springs. After spending five years in Shelby toiling at the book, writing his Mercury pieces, and, beginning in 1935, contributing weekly book reviews to the News, he would return in October, 1937 to this small, but eclectic, liberal newspaper as full-time associate editor responsible for writing editorials, some on national and state politics, but principally foreign affairs. This time, his stint would last not quite four years. (On the Sunday this photo appeared, Cash contributed two articles, one a not so favorable review of Hilaire Belloc's The Battleground, on the history of Syria and Palestine, and the other, titled "Hang the Teachers!"--well, enough said... )

Letter from old friend, W.R. Gary, writing in praise of "Hang the Teachers!" and also indicating his expectancy of the book, having seen in the News the above picture and caption. Like everyone else, however, he would have to wait five more years for his friend to complete the work.

On April 12, 1936, in this News article, (fully readable text of which is elsewhere at this site), Cash bemoaned the "passing" of what he saw as Hemingway's prime as a writer. (Cash's own writing suggests that he certainly was no fan of the "minimalist" style, the eventual common fashion of which is largely attributed to the popularity of Hemingway's later writing. Cash rather saw this as an excuse not to think while reading (and writing), rather than some purist technique of style, as it seems to have come to be regarded by most fiction publishers and writers today. Indeed, some contemporary academics complain of Cash that his style is one where he sees no reason to use one word when two or more will do. The articles in the News, however, belie this notion and indeed, most harsh critics of Cash appear to forget that the ideas communicated within the Mercury and in the book required for the times a measure of overstated and often deliberately convoluted articulation to place the thought process in more Fabian mode and also protect Cash from the tar and the feather which often followed those who wrote "against his own kind" as Cash surely appeared to many to have done. And, a fortiori, it was no mean task to stick the entire cultural history of the South into 430 pages of print in 1941.) In the cold draw of history, the above article is passing strange in many ways as Hemingway would commit suicide in Ketchum, Idaho in the early morning hours of July 2, 1961, precisely 20 years and 12 hours after Cash's supposed suicide in Mexico City.

On June 28, 1936, Cash humorously displays his past frustrating experience, albeit brief, as a high school and college English teacher in this column, "What Is A Reader?", bemoaning how few people, even well-educated people, actually read what they "read". And if, for your eyesight, you are unable to read it, take heart, the full text of the article (much more to read than just the above even if you can perchance read it) is within the News articles section of this site in normal, readable print. (Sorry, but to make it bigger and more easily readable requires so much memory on the computer's main server that you would likely be unable to read very much else at this site.)

The Move to Charlotte - October, 1937

The stately Frederick Apartments on Church Street in Charlotte, as it appears today in October, 1998 much as it did 61 years ago, just a short walk to the central area of downtown.

Such proximity to work, the favorite socializing spot, The Little Pep Bar & Grill, and the "inadequate" library made it ideal for Jack Cash who never owned an automobile in his life. (And given his poor depth perception, most agree that walking was better for his health in any event.) After a brief stay at the Selwyn Hotel, he signed a lease for apartment 308, third floor, right side, at the Frederick in the late fall of 1937. During his tenure at the art deco inspired building, he finished the published version of The Mind of the South, writing a little less than one-third of the manuscript plus substantial polishing of that completed in Shelby. His friend on the News and neighbor at the Frederick, Pete McKnight, was still alive when Joseph Morrison wrote the first biography of Cash in the mid-Sixties. McKnight reported that on weekends Cash would fall asleep listening to his favorite 78's, usually Beethoven, Mozart or Sibelius, while reading "heavy old books" and sipping beer or busthead; when McKnight would hear the echoes in the hallway of the needle skipping to the inner groove, or the refrain of Beethoven's C Minor Symphony playing ad infinitum on Cash's new, expensive Garrard record changer, he would dutifully go to Cash's apartment and turn off the phonograph. McKnight also told of sometimes seeing a ghastly looking "goddamming" image of Cash standing in the hallway in his underwear vituperating at his young working female neighbors for playing their crooning radio pop swing hip 40's be-bop a bit too loud for his more classical ears. Not to be outdone, however, if his complaints went unheard, Jack would stick "The Ride of the Valkyries" on his changer and turn the knob to the higher numbers. (Source: Southern Prophet, Joseph L. Morrison, Knopf, 1967, pp. 76-77) (Could this image have inspired Francis Ford Coppola?) (Someone in Hollywood liked the area; in 1994, a climactic scene for the film "Nell" was shot at the Day's Inn, within 200 feet of the Frederick, looking toward the large gothic Methodist church across the street.) And it was down these steps of the Frederick which Cash took a tumble in January, 1939, banged his head, and offered it for weeks as an excuse to the Knopfs for missing another years overdue promised deadline for the manuscript. The many self-effacing apologies for "laziness" and recurrent excuses for health obscured the real reason for the delay--which the Knopfs seemed to understand--that Cash insisted on getting it right both as to style and substance.

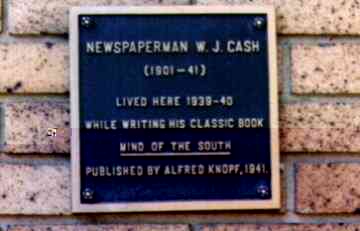

For all the Frederick's worts, Cash enjoyed his stay here as evidenced by the prodigious work-product in the three years at the plant--some 2,500 articles and editorials for the News and a finished manuscript at long last for the Knopfs. "God be praised," wrote Mr. Knopf to Cash, when the package arrived by express on August 1, 1940. Cash stayed until his marriage on Christmas Eve, 1940, after which he and Mary moved to the undoubtedly blander Blandwood Apartments in a quiet residential area of Charlotte. The little plaque to the right of the doors (see closeup below) commemorates Cash's tenancy (albeit with incorrect dates for his birth and the beginning of his residence). Just across the street today rises a massive shiny-new glass office building owned by NationsBank, as evidenced in the above picture by the bit of wooden construction scaffolding in the bottom left corner. Would Cash call this plump bulging behemoth growing out of the ground across the street from his old haunt "Progress" or just another "goodsbox skyscraper" in a place with no more need for the thing than a dog does a manse 'neath a mansard? (...Or something like that.)

The little plaque was placed in the early 1980's as part of a civic campaign by Charlotte to celebrate its best known literati. Similar plaques, for instance, were placed on the house from which Harry Golden, a friend of Cash's first biographer, Joseph L. Morrison, wrote his many literary humoresques, such as Only in America, For 2 Cents Plain, and You're Entitle', and edited his bi-monthly opinion piece, the Carolina Israelite; and also on the old house where the young Carson McCullers, whom Cash met in 1941, spent a year in 1939-1940, not long before publishing The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Reflections in a Golden Eye.

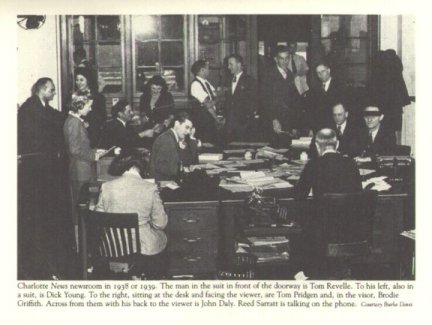

Somewhat remindful of the movie "Front Page", the Charlotte News newsroom in 1938 or 39. Identifiable personnel are reporters and Cash friends Tom Revelle, (in front of doorway), Dick Young, (in front of door), Tom Pridgen, (to the right of Young), Brodie Griffith ( in visor), John Daly, (sitting at desk with back to camera), and Reed Surratt (sitting at desk talking on phone). (Reprinted from W.J. Cash: A Life, by Bruce Clayton, L.S.U. Press, 1991)

The Charlotte News Building at Church and Trade Streets, as it appeared in the 1930's.

Letter showing Cash's yearly earnings in 1939 of $2,743. From 1937-1941, he would regularly send $50 per month of his earnings to his parents as a means of trying to pay them back for all of their financial support during the hard times of the Twenties and early Thirties when Cash earned next to nothing. Cash needed this letter establishing his income so that he could co-sign an F.H.A. loan for his father to buy the Morgan Street property in Shelby. (See below) This letter was written three days before Cash bundled the last of the finished manuscript and mailed it to New York to the anxiously awaiting hands of the Knopfs.

Despite Cash's prodigious writing, he rarely wrote letters. Assuming Cash to be enmeshed in the work on the book, noted UNC sociologist Howard Odum wryly remarked to Alfred Knopf on December 31, 1938, when Cash had not responded for several weeks to some suggestions by Odum on the manuscript, "I suspect he is not a very good correspondent." Aside from his letters to the Knopfs, and a few assorted notes of thanks after the book was published, this letter acknowledging his willingness to co-sign his father's F.H.A. loan is one of the few surviving letters. (Most of the originals of Cash's correspondence which does exist are in the files of the Knopf Publishing Company, the Joseph L. Morrison Papers within the University of North Carolina Southern Historical Collection, the Wake Forest University Library, and the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas.)

![]()

North Georgia Review

Edited by Lillian Smith and Paula Snelling Spring, 1940

![]()

Book Review: A SEA ISLAND LADY

BY W. J. CASH

Site ed. note: W. J. Cash befriended novelist and early civil rights advocate Lillian Smith during the writing of The Mind of the South. She and co-editor Paula Snelling published early excerpts from the Cash manuscript in 1936 in their eclectic North Georgia Review and would give it a glowing review in early 1941, publishing another pre-publication excerpt in late 1940. A year after Cash wrote this book review for the North Georgia Review, waxing despairingly of the absence of a truly fine novel on the Civil War and post-Civil War period, he would venture to Old Screamer Mountain in Clayton, Georgia one Sunday in March to meet with Ms. Smith and Ms. Snelling together with Karl Menninger. On departure, Cash would tell his newlywed wife Mary that it was the best day of his life.

Of interest regarding Cash's comments here is the fact that in September, 1940 when hashing out ideas at the encouragement of Al Knopf for his next major writing project, Cash mulled over the notion of a novel in tetralogy, one for each of major segments of the Civil War, in series reaching climax at "Sumter, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Richmond and Appomattox". Knopf nixed the notion at the time because of the plethora of Civil War novels on the market in the wake of Gone With the Wind and Cash's lack of recognition as a novelist. He favored instead Cash's also proposed novel on "one Andrew Bates" following his development from just after Reconstruction to 1939. Another idea Cash threw out was going to New Orleans and doing a quick biography in less than a year on Huey Long to take advantage of whatever recognition in non-fiction Mind brought him--but Knopf informed him that his company already had a contract for such a biography with another author. Cash went to New York in September and visited with the Knopfs to discuss future writing plans and within a month he issued his third and finally successful Guggenheim application stating his plans to write the Bates novel on the Old South's last whimpers to the New, the writing to take place in Mexico City with intended completion by January, 1942.

The one sure way to the best seller lists these days seems to be to write a Mack Truck novel. I remember a time back in the Aurignacian 'Twenties when publishers and critics were unanimously warning arrived and would-be writers that the public of the machine age had grown much too impatient to read a book of more than 250 pages, and that the best system was probably to hold it under 200. The earlier fate of Look Homeward, Angel appeared to bear that out. But then came Anthony Adverse. And now the publishers seem almost to believe that the public won't read anything unless it runs at least, 1,292 pages. And the public bears them out; at any rate to the point of insuring that each new Mack Truck sets its author up to a Cadillac V-16, four houses, a power boat, and an annuity for the rest of his long days.

All of which is by way of saying that it seems to me that Francis Griswold would have written a much better book if he had forgotten Gone With the Wind when he was turning out A Sea Island Lady.

I have no quarrel with long novels; on the contrary, I have a decided weakness for them. But Tom Jones and The Peasants and War and Peace and The Brothers Karamazov and, to a lesser extent, A la Recherche du Temps Perdu and Jean Christophe and Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River are long novels because the vastness of their design requires it—because to set forth the absolutely germane or the at least pertinent it is necessary to use up so much white space, the laws of physics being what they are. But I do not think that the same is true of A Sea Island Lady any more than it is true of Anthony Adverse or Gone With the Wind.

That is not to say that the book is without merit. Mr. Griswold's prose is often pedestrian and a little inept, but it is always smooth and sometimes it attains a considerable distinction. And the descriptions of the sea islands about Beaufort, S. C., and of Beaufort itself are exceedingly well done. It is one of the ironies of the novel that Mr. Griswold is full of nostalgia for the beauties and the slow and languorous way of old Beaufort, mildly indignant about the ravages of Progress in the place—and that the excellence of his description is sure to bring down an influx of tourists upon the town and so speed the ravages of Progress.

The whole background of the novel, both physical and social, is indeed a big theme. And in some respects Mr. Griswold has done a good job of it. A Yankee himself, he has had the discretion to make the protagonist of the tale, Emily, a Yankee come South to play "missionary" to the black men freed by the Civil War. Such "missionaries" had a lot to do with the bitterness of feeling engendered in the South by Reconstruction, and one can easily understand why when looking at the Rev. Atwood Moffet, who has married Emily and fetched her down for the holy work, and Mrs. Sager.

The chapters dealing with this period are the best in the book, and it had better have ended with them. Mr. Griswold, who has lived much at and around Beaufort, has absorbed the stories native to the section thoroughly and has a better grasp of southern psychology in the time than most northerners have ever managed to attain. Sometimes he is guilty of the fault of a good many Yankees, that of leaning too far to the southern side, once their sympathies have been enlisted for it. And throughout the only ones among his principal characters who really come to life are those from above the Potomac River. Atwell's progress into scoundrelism and his taking up with a former Negro slave of the Fenwicks is made convincing enough. So are the adventures of Emily, within certain limits. But Stephen Fenwick, whom Emily eventually marries, is still very largely a shadowy ghost from the legend of the Old South and Thomas Nelson Page, despite Mr. Griswold's best efforts to lend him individual character. The only fully convincing southern whites in the book are Stephen's incredible old aunts—incredible, that is, in any other land than Dixie—and they are the sort of stock characters no one could miss.

The last half of the book seems to me simply dull and unnecessary. Mr. Griswold has followed the same formula throughout that Margaret Mitchell followed in Gone With the Wind. That is to say, he has collected all the appalling and dramatic things which ever happened to anybody in the Beaufort district, has added a generous portion of others from his imagination, and then has had them all happen to a single woman in a single lifetime. It is, of course, a dubious method, under any view of the case. But he succeeds in making it plausible so long as the theory is confined to the last days of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the poverty-haunted decades that followed. But, after that, it becomes just a bore. You yawn, or you laugh as the incidents pile up intolerably, but you are neither moved nor edified.

Ultimately, Emily, no weakling, is not a character powerful enough to bear the building of a novel of 964 large and close-packed pages on her shoulders. And a good part of that length is explained by detail which has no real relation to the story. What Emily thought, what she did in the garden, what she read in the newspaper, this and that, most tiresomely.

Like The Tides of Malvern, this new novel by Mr. Griswold fails to quite come off. Of the two, I think, in fact, that the first was the better.

And like Gone With the Wind, A Sea Island Lady is another epic of Reconstruction which is less than an epic. The Civil War and the years which followed it undoubtedly offer the most dramatic and powerful material available to the American novelist, and above all to the southern novelist. And someday we shall probably get a really great novel out of it. But we haven't yet.

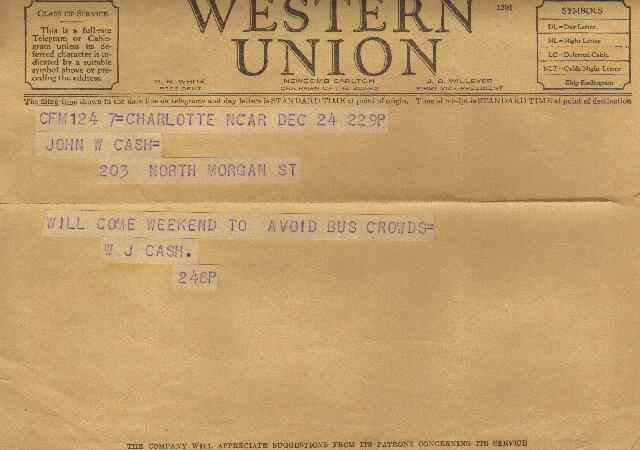

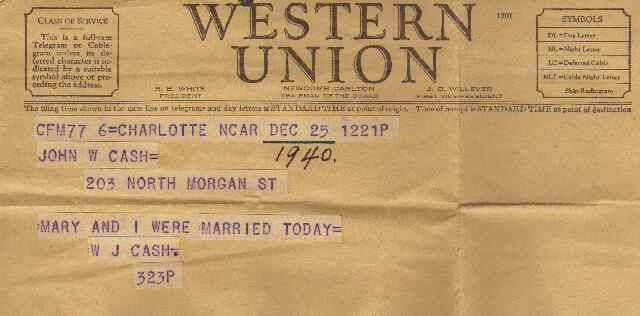

Marriage - December 25, 1940

Cash had told Mary a year earlier that he would not consider marriage until the book was finished. That having taken place the previous July, perhaps we here find Jack dissembling to his father by omission, (though it is by no means clear that Cash and Mary planned anything at that particular time); Wilbur would wed Mary Bagley Ross about 12 hours after this telegram was sent. The two were urged in the process by old friends of Mary, attorney Frank McCleneghen and his wife, Laura, while all were reportedly slightly in their cups. On this frosty Christmas Eve, the constant couple of two and a half years slipped quietly over the South Carolina border with the McCleneghens to greet an all-hours justice of the peace at around 2:00 a.m. in York, (the Gretna Green of the region), and then and there accepted their vows. McCleneghen loaned his fraternity ring to Cash for the occasion. By Mary's account in 1967, with the exception of the last 24 hours of Cash's life, the six months of marriage went well. Mary had previously been married once to a fairly wealthy Charlotte businessman named Northrup, but Cash had remained single to that point. Obviously excited by the prospect, Cash hurriedly wired Alfred Knopf two days later that he must change the book's biographical note stating Cash's unmarried status, saying, "He is now!"

Mary was introduced to Wilbur in spring, 1938 by Mary's cousin and Cash's friend and fellow News writer, Cameron Shipp, at a Charlotte book fair which Shipp had organized (and to which the aging Thomas Dixon was pointedly not invited). Among the stellar writers in attendance were Charlotte's own premier novelist, Marian Sims, Raleigh newsman and author Jonathan Daniels (who would befriend Cash and sponsor him three years later for the Guggenheim Fellowship), and well-known North Carolina playwright Paul Green. Cash appeared to enjoy the other authors but was unwilling to discuss his own book, abruptly telling Emery Wister, a young News staffer who inquired about the book's progress, that it was "nowhere near finished". Mary had submitted occasional book reviews to the News, though was not a regular member of the staff. Being independent and something of an iconoclast herself, she had read and enjoyed Cash since 1932 when someone loaned her "Close View of a Calvinist Lhasa", the rueful poke in the eye to her native Charlotte from The Mercury. Wilbur and Mary instantly became companions, Mary announcing to her mother the day after meeting Cash that she had just met a "fat country boy" who she intended to marry. Observers felt that her presence in his life seemed to soften Cash's sometimes crusty demeanor--or at any rate what others perceived as such. Mary on the other hand described her first impression of him to be that of a shy youthful bachelor with a small pot belly, a bad haircut covering a mostly bald pate, and sporting a bemused twinkle in his eye which she took to be love at first sight--not at all the "crusty and sassy old gentleman" she had conjured in her mind from reading him from afar. (Source: W.J. Cash: A Life, by Bruce Clayton, L.S.U. Press, 1991, pp. 145-150)

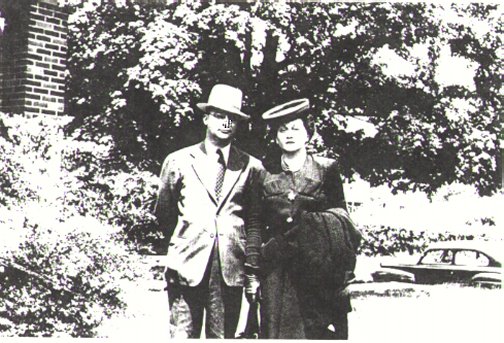

This telegram was sent to Cash's parents by Cash's sister Bertie and brother-in law Charles from Lumberton three days after Wilbur and Mary were married. (As Cash never owned or drove a car, he always had to rely on others or the buses for transport. Such had made the writing of the book more time-consuming than it might have been otherwise as he had to travel by bus to Chapel Hill to obtain most primary research material and serious scholarly works on the South; this limitation, however, was turned into a strength of the book as Cash was forced by financial considerations and lack of depth perception to deal with the tools he had at his disposal, first his native observation and imagination, and then the records, anecdotal and plain, of family origins, marriages, land deals, and the like contained within the small North and South Carolina courthouses within walking and thumbing distance of his home.) Subsisting on writers' salaries, Wilbur and Mary could not afford a proper immediate honeymoon, even by bus, and thus the trip by train to Mexico in May via New Orleans, Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio became their belated celebration.

Wilbur and Mary five months after marriage, May 25, 1941.

And the most published picture of Cash, originally made in late 1940, shows yet more dramatic aging in only a five year period since the two pictures near the top of this page. When it was used to accompany a review in Time in February, 1941, he told Mary that it made him look like a gangster; she replied that since he had chosen it for Knopf to use for publicity, he had only himself to blame... More evidence of Cash's often rueful self-parody?