Publication, Review, Mexico City

{Page 2 of 3--Review & Departure}

Go

to Quick Navigation Bars at Bottom of Page for Other

Sections of Site |

Kind letter from the Boiling Springs librarian regarding the publication and receipt of the Guggenheim.

Poor Cash was both honored and besieged by requests such as this well-meaning one from his alma mater requesting a donation of a copy of his book. Readers did not realize the paltry sums earned by Cash from the book and that even his $2,000 Guggenheim prize would only barely see Mary and him through the year to come in Mexico. In those days, of course, Wake Forest was a small Baptist college with precious few financial resources. Whether Cash honored the request is not known. Regardless, many items, including the original manuscript of the book and the Underwood typewriter on which it was written, have been donated to Wake Forest in the past decade, primarily by Cash's sister's family.

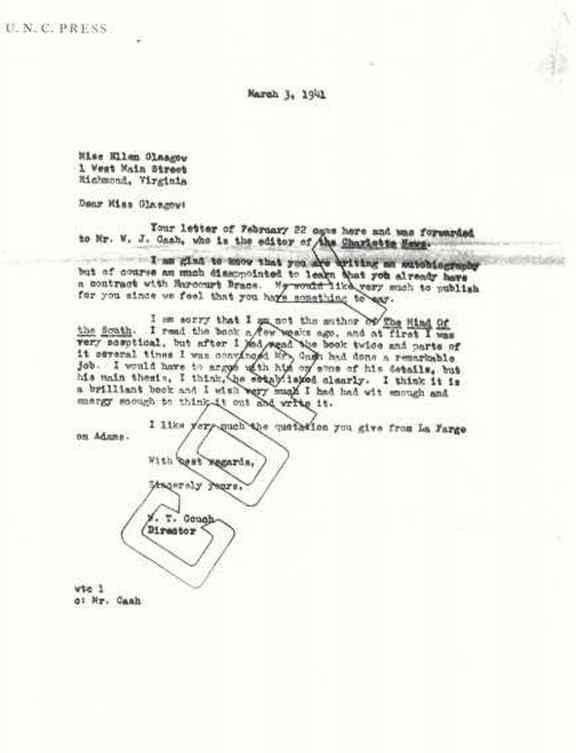

Letter from W.T. Couch, Director of the U.N.C. Press, expressing a common complaint and revision still heard to this day on first and second readings of the book, and inviting Cash to appear at the old Bull's Head Bookshop in Chapel Hill for a talk in April. (Perhaps, this was poetic irony of a sort as a favorite expression in the Cash family was to call a stubborn loved one "an old bull head". ) Cash also received an invitation to speak in Chapel Hill to high school newspaper editors at the N.C. Scholastic Press Institute from Walter Spearman, former Charlotte News colleague who had moved to the U.N.C. School of Journalism of which he would later become Dean. (See letter from Spearman at the Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library.) Cash would go and there, without knowing it, would have among his audience his first biographer, the then 22 year old Joseph L. Morrison.

Couch's letter also refers to a letter in praise of his book from Ellen Glasgow, renowned novelist from Richmond, who Cash admired as the pre-eminent Southern writer of the time and did not hesitate to say so in print. (Mind of the South, pp. 144, 374-375 of 1941 ed.)

Below is Couch's response to Ms. Glasgow. His reference to "La Farge on Adams" was Ms. Glasgow's remark by way of questioning Cash as to why he would rely on Henry Adams as "the final authority on the Southern mind". Cash had actually only cited a quote from Adams' Education, regarding Roony Lee, the son of Robert E. Lee, who Adams used as example of the quintessential Nineteenth century Southerner who "'had no mind; he had temperament. He was not a scholar; he had no intellectual training; he could not analyze an idea, and he could not even conceive of admitting two...'" (Mind, Book I, Chap. III, section 12, pp. 98-99 of 1941 ed.) But in the latter sections of the book Cash had contrasted this "savage ideal" with that of the New South where gradually increasingly from 1900, "a decisive breach had been made in the savage ideal, in the historical solidity and rigidly exacted uniformity of the South--that the modern mind had been established within the gates, and that here at long last there was springing up in the South, a growing body of men--small enough when set against the mass of the South but vastly large when set against anything of the kind which had ever existed in Dixie before--who had broken fully or largely out of that pattern described by Henry Adams in the case of Roony Lee and fixed by Reconstruction; men who deliberately chose to know and think rather than merely to feel in terms fixed finally by Southern patriotism and the prejudices associated with it; men capable of detachment and actively engaged in analysis and criticism of the South itself." (Mind, Book III, Chap. II, section 23, pp. 326-327 of 1941 ed.)

The quote from Adams was placed in Mind by Cash in the latter thirties to afford the kind of additional "authority" for his thesis which the Knopf editors requested after seeing initial drafts of the first two sections of the book in early 1936--a criticism which Cash accepted as accurate but also said in response to Knopf on May 17, 1936 that because of the nature of the thing, being essentially "one man's view--a sort of personal report", the book "must rest in large part on the authority of my imagination and understanding at play on a pattern into which I was born and which I have lived most of my life--on the reader's recognition that it fits with the record and makes comprehensible, in terms of common human psychology, a great deal that has hitherto been comprehensible only in terms of some such improbable hypothesis as the inherent inferiority (or, as the patriots have it, superiority) of the South."

Ms. Glasgow inquired of Cash at the close of her letter, "Do you recall an amusing passage in 'New England: Indian Summer' [in The Education of Henry Adams]? He (John La Farge) dreamed, after one of their arguments, that he heard the mind of Adams making a great clatter in the room. He awoke,--it was only a rat." Just exactly what Ms. Glasgow meant--humorous sideswipe at Cash?--is not clear as an examination of the chapter in Education finds Adams discussing his opinions of La Farge, the esoteric artist whose works in church murals and stained glass were widely regarded in the latter Nineteeth century, and La Farge of Adams, but does not prove up any dreams or rats! In fairness, she was ill at the time and may have simply confused it with another scene. Ah, well, writers... Ms. Glasgow won a Pulitzer for her last novel, published in 1941, In This Our Life.

Letter from old friend congratulating Cash on book and Guggenheim. Reference to "Hell's Corner" is of unknown significance.

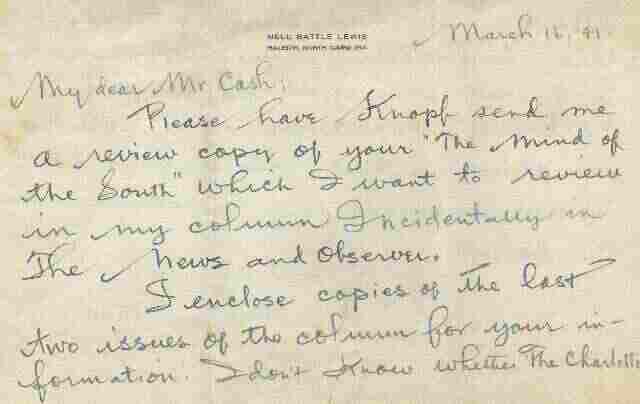

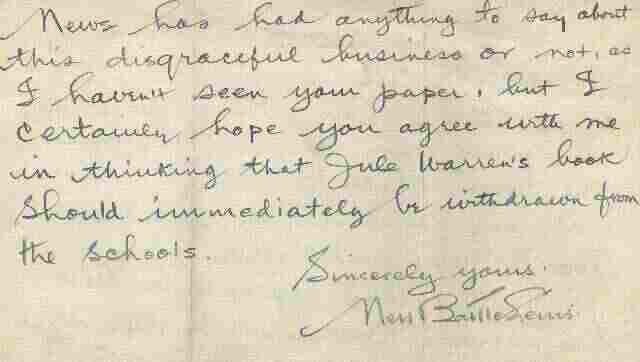

Letter from Nell Battle Lewis of the Raleigh News and Observer requesting a copy of the book for review. She subsequently gave high praise to the book and later in December gave further praise to the Mayflower Society for honoring it. (Cash had mentioned her as a principled, courageous contemporary editorialist. (Mind of the South, pp 339, 354))

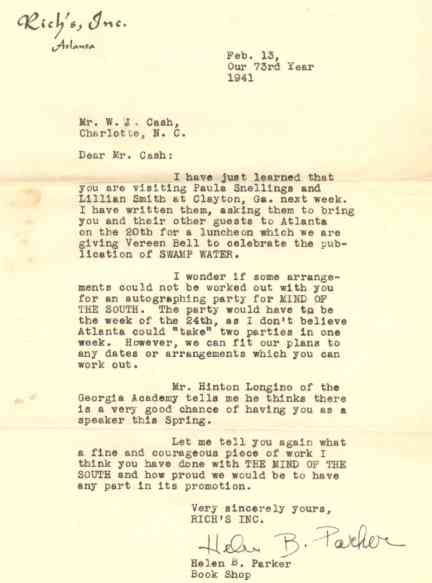

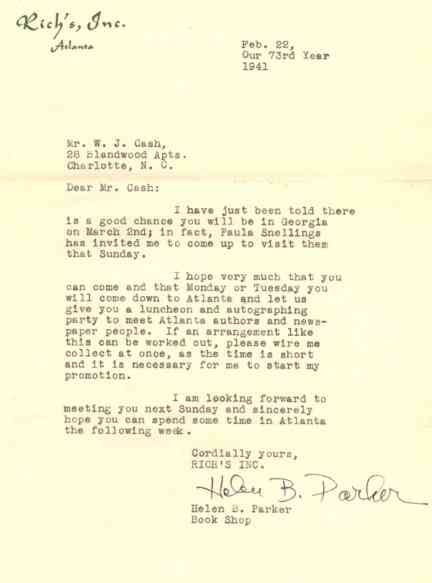

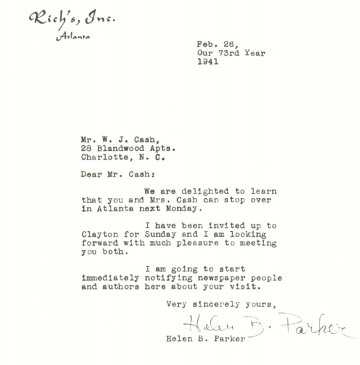

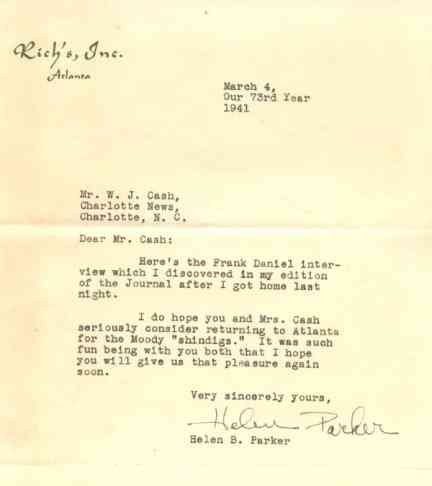

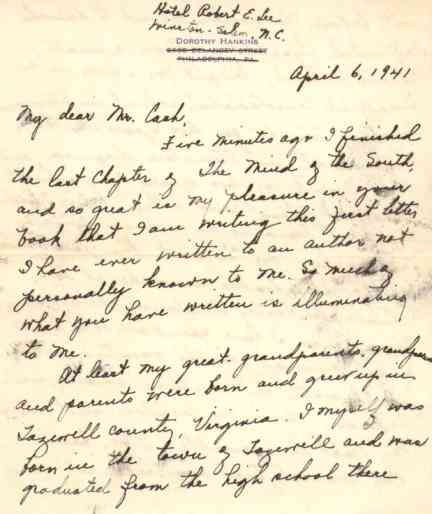

As the book was a best seller in Atlanta, Helen Parker, book buyer for Rich's Department Store, in a series of four letters below, had encouraged Cash to come down for a party and book signing. The matter turned into a joyous trip for both Wilbur and Mary on the weekend of February 28-March 3 as they were wined and dined by the John Marshes, also known as Margaret Mitchell and her husband, after spending what Cash called the best day of his life on Sunday in the tiny mountain village of Clayton, Georgia at Old Screamer Mountain with his friends, novelist and civil rights activist, Lillian Smith, and Paula Snelling, co-editors of the North Georgia Review, a literary magazine of the time. On hand also was noted psychiatrist Karl Menninger who Cash thought a "capital fellow", and who ironically had published a book in 1938 about suicide titled, Man Against Himself. Cash had been asked to read the draft manuscript of what became Ms. Smith's controversial best selling novel, Strange Fruit, eventually published in 1944, about a love affair between a white man and a black woman in a small Southern town. Cash obliged and gave her a glowing preliminary review of the draft. (See Snelling letter to Cash of January 10 at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library. The article which Cash produced for The Saturday Review of Literature, December 28, 1940, of which Ms. Snelling makes mention, was an abstract from The Mind of the South, Book II, Chap. II, last para. of section 12, beginning "Always...", and section 13, then continuing from Book III, Chap. III, section 10, beginning second paragraph, and section 11, ending at "...leisureliness", omitting last phrases, pp. 141-144, 374-384 of 1941 ed.)

Cash also, according to Mary, enjoyed the company of Margaret Mitchell at the Piedmont Driving Club in Atlanta the following day, but was nervously apologetic to her for having called Gone With the Wind "sentimental" in the latter pages of The Mind of the South, (Mind of the South, pp. 419-420), not to mention another sideswipe at it in The North Georgia Review in a book review in spring, 1940. (See book review of A Sea Island Lady in "The Writing Years" section of the Photo Gallery.) Nevertheless, the two hit it off amicably enough and Ms. Mitchell even wrote to Cash twice, on April 16 and April 28, wishing him success on the novel and providing extended praise of The Mind of the South, saying that her "scholarly father" had called it "a Southern milestone". The book review to which Ms. Mitchell referred in her April 28 letter is that of Richmond C. Beatty, one of the Agrarian group in Nashville which appeared in the Nashville Banner February 26, and was the one unremitting sour note among reviewers of Mind. Cash had mailed a copy of the review to her in good humor by way of apology for his "'sentimental' crack":

April 23, 1941

Dear Margaret Mitchell Marsh:

It was good of you to write about the Guggenheim and to say such pleasant things. I agree that to wish that the second book shall come easily is the best thing one author could with another. I observe that I said "author," a word that always has tickled me.

Ever since we were in Atlanta, both of us intended to write you and express thanks for your kindness while we were there. The drinks practically saved our lives. But a writer who is too damned poor to afford a secretary is in nearly as hellish a fix as one who is so plagued by ardent admirers that she has to hire several. I have been trying to do some magazine stuff, and between that and the letters I have been swamped. In fact, I have about abandoned hope of ever getting most of the letters answered despite my conscience about the matter.

About that "sentimental" crack: thinking it over, I have an idea that what inspired that carelessly thrown-off judgement was the feeling that your "good" characters were shadowy. On reflection, I think the feeling may have proceeded less from themselves than from the fact that they were set beside that flamboyant wench, Scarlett. There were good women all over the place in the South, of course. But Scarlett is a female to go along with Becky Sharp, wholly vivid and convincing. Beside her, everybody else in the book, including even Butler, seems almost an abstraction. I hope you don't mind my saying it; I know how stupid the judgements of others on his creations sometimes seem to a writer. Indeed, I am often madder at the critics who are trying to be kind than to those obviously out to do me dirt. But if I offend, take a look at the enclosure and you'll probably feel better. Lit'ry criticism in the highly genteel Agrarian circles starts with the ascription of canine ancestry and goes up.

We are, of course, delighted with the Fellowship, but horribly afraid that the war will break and probably keep us from going at all or make us feel bound to return before we get a a look around. At present our plans call for sailing from New Orleans for Vera Cruz on June 6. We'll probably stop by Atlanta on the way down, and if so we hope very much to see you and Mr. Marsh again.

My thanks to your father for that immensely pleasing judgment.

The best from both of us.

Cordially,

W. J. Cash

Incidentally, both of us were amused in view of the Communist tirade against you, to find the New Masses concluding that the "Mind" was a sentimental book.

Note that the trip by ship from New Orleans to Vera Cruz would be replaced by the train swing through Texas for the commencement address, the invitation for which was mailed by Homer Rainey the day following Cash's writing this letter. Unsigned copy of Cash letter to Margaret Mitchell supplied by Margaret Mitchell's daughter in 1964 to Joseph L. Morrison, as contained in Morrison Papers, University of North Carolina Southern Historial Collection. (See Red Clay Reader article by Mary Cash Maury at this site and see W.J. Cash: A Life, by Bruce Clayton, L.S.U. Press, 1991, pp. 174-177, for further description of this memorable weekend in Cash's life.)

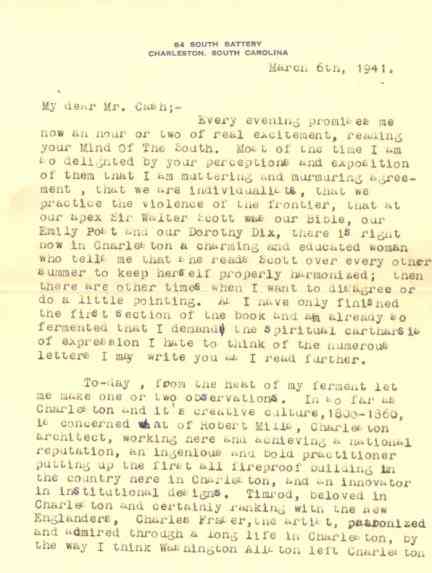

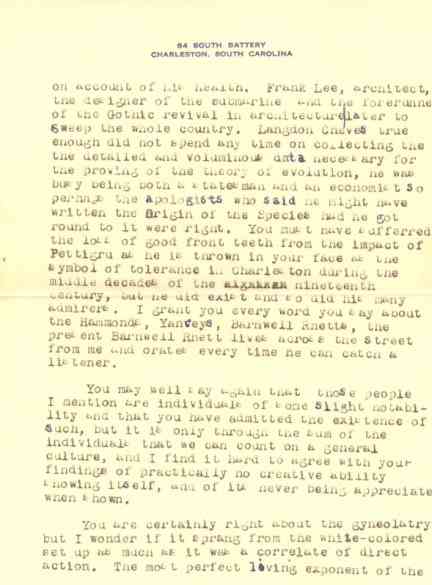

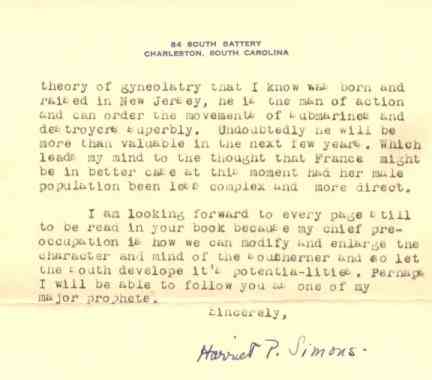

Two letters from readers, an articulate and friendly one above and a fairly amazing one from someone "in the heat of [her] ferment" in Charleston below. Cash received a mixture of mail, mostly praising the book, some seemingly missing most of the point.

The writer waxes cryptic at the end and does not say just who is this "most perfect living exponent of gyneolatry", the "man of action" from New Jersey who "can order the movements of submarines and destroyers superbly". (While it does not make altogether good sense in context, we are left to guess that she is possibly referring to America Firster Charles Lindbergh of New Jersey whom Cash despised as using his fame to divide the country and encourage the sell-out of Great Britain to Hitler; Cash had so editorialized in The News on more than one occasion in April and May, 1941. Ann Morrow Lindbergh had published a book in 1940 titled The Wave of the Future in which she posited, as did many other prominent people of the time, that Nazi Germany was a necessary evil to stabilize Europe's faltering economy and would ultimately lead to peace and prosperity for all. Cash cryptically remarks of the Lindberghs and the Firsters at the beginning of his Texas Commencement Address in June.)

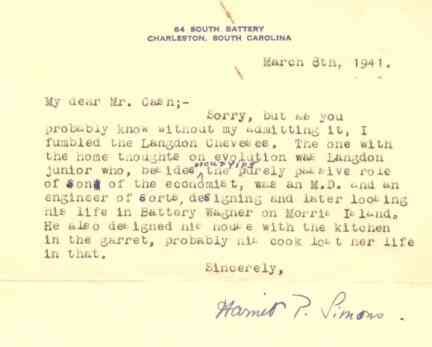

The same letter writer then went so far as to deliver the follow-up letter below correcting her mistake on Langdon Cheves and ending with a comment about him placing his kitchen in the garret from which "probably the cook lost her life in that".

The Ides of March proved fateful for Cash. His sister Bertie underwent surgery for removal of a cyst from her breast. Cash was so upset that he had to be comforted over beer by Bertie's husband Charles as the operation proceeded. He had the day before received news that he had won the Guggenheim Fellowship for which he had unsuccessfully applied twice during the early to late Thirties. This time, the success of the book and the sponsorship by former Guggenheim recipient, Jonathan Daniels, and by the Knopfs propelled him to the grant. Besides Daniels, only two other North Carolinians, Thomas Wolfe and Paul Green, had ever received a Guggenheim. (See Guggenheim Foundation letter to Cash of March 12, announcing grant at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library.) Finally, in all of the mixed-up confusion, Cash forgot to file his income tax returns, in those days due on March 15.

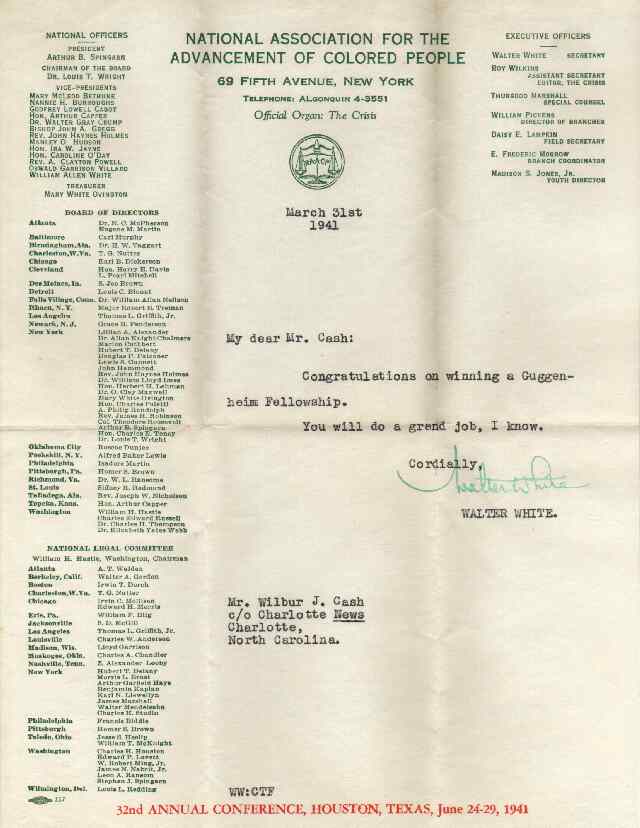

This was the second letter of congratulations from Walter White, Executive Secretary of the N.A.A.C.P. The first had thanked Cash for the book itself, making special note of its contribution to uncovering and publicizing the Southern code of lynching. (Note the name of "Special Counsel" Thurgood Marshall on the letterhead, who would in 1954 be the lead counsel in arguments before the United States Supreme Court in the landmark desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education, and would also become the first African-American appointed to the Supreme Court, appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967. Marshall served on the Court until 1991.)

In his fall, 1940 application for the Guggenheim grant, Cash had written:

I propose to write a novel, which is already in progress. Primarily, it will be the story of the character and development of a certain Andrew Bates, born the son of a wealthy cotton mill family in piedmont North Carolina in 1900, down until the outbreak of the second world war in 1939.

Over and beyond that it will be also the story of his father and grandfather. And beyond that, again, the story of the rise of an industrial town in the South after the introduction of the idea of Progress after 1880.

While the novel is being written I should like to live in Mexico City. The place has been chosen with an eye to both my journalistic future and my hopes for a career as a writer. It seems to me that Americans who deal in the printed word are going to have to pay a great deal more attention to Latin America in the future than has been the case in the past. And Mexico City seems to me to be the best place to get acquainted with it.

The novel will run, I think, to about a hundred and fifty thousand words. I expect to complete it by January 1, 1942.

I have published no fiction and have submitted none to a publisher. Nevertheless, I have always been, and remain, confident that my primary talent lies in that field. The Mind of the South, I am sure, is properly described as "creative writing." But I am well aware of the difference between social analysis and fiction. I believe I can do the latter better than the former. And I expect to have enough of the novel ready by the time the fellowship selection is made to offer proof of my belief.

Cash had in 1936 applied for a Guggenheim to spend a year in Nazi Germany, primarily in Berlin and Munich, writing a novel on the Old South, "as it was, rather than as the legend-mongers have made it out to be", centering on his archetypal "Old Irishman" of The Mind of the South based, he later told Knopf, on his great-great grandfather. He would write this novel while studying the culture of Germany. "I have a particular interest in the Nazi regime and movement as a historical phenomenon, and want an opportunity to observe it at close range," he told them. But by 1940 he had dismissed the idea as impossible given the international situation. In fact, therefore, he probably chose Mexico City--if he chose it--so that he could study more closely the Nazi mindset as Nazi spies were rumored to be there--and, of course, were in fact there in substantial numbers. When Mexico finally enacted a "get-tough" policy toward the Nazi spies in November, 1941, and gave it sloth-like action with arrests in late February, 1942, 240 suspected spies, those who had not already fled by summer's end when Mexico closed the German consulates, were arrested. Only two were ever tried for espionage; none were convicted. All were deported back to Europe. At the time, however, the regime of newly elected president, Avila Camacho, had been reporting since early 1941 that the Nazi spies were washed up in Mexico and had left the country. (See The Shadow War, by Leslie Rout and John Bratzel, 1986, pp. 71, 80, 85-86; series of articles on Mexico City by Raymond Clapper, April 18-23, 1941, positing "75-150" spies left, mainly in the provinces.)

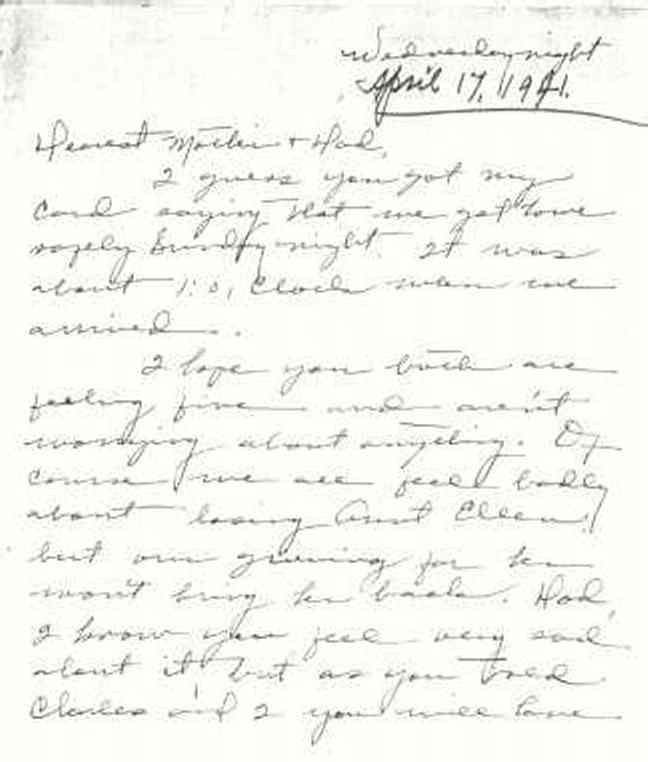

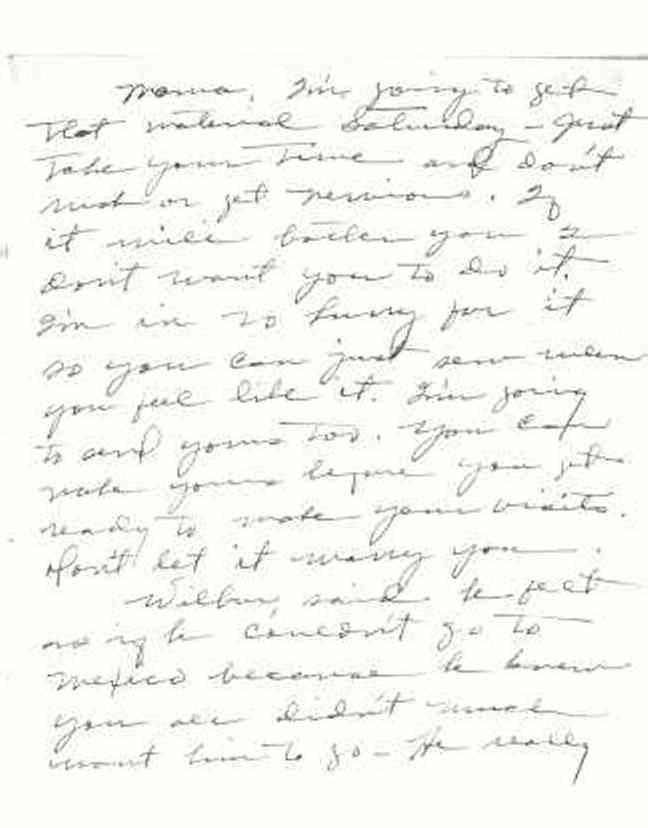

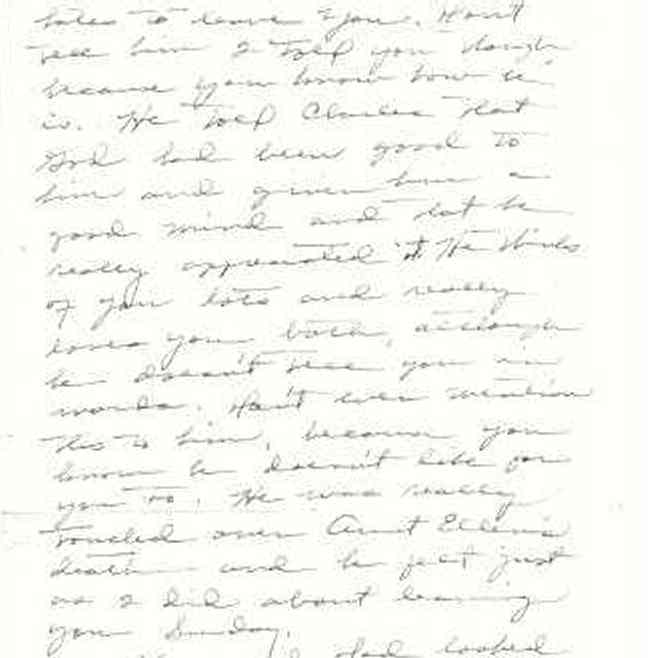

Recovered from surgery, sister Bertie wrote to her mother and father on April 17, offering comfort for the loss of John's sister Ellen, from whose funeral the family had just returned. Bertie makes mention of her discussion with Wilbur about him not wishing to go to Mexico because he was aware that both parents did not want him to go. They wanted instead for him to be a writer-in-residence in Chapel Hill, an option available to Cash. Bertie also speaks of how much Wilbur loves them "although he doesn't tell you in words". She then adds, "Don't ever mention this to him, because you know he doesn't like for you to." Such is consistent with Cash's introverted personality and his usually dry demeanor. He tended to mask his tender sensitivities with what appeared to some to be a cold, even cynical, exterior.

Letter from News Editor and Cash employer, J.E. Dowd, to Cash's father expressing how the receipt by Cash of the Guggenheim left him "of two minds", the one, proud to have a member of his staff so honored and the other, regretting to lose "so good an editorial writer". Curiously, when Cash had been nominated in 1940 for a Nieman Fellowship to Harvard, Dowd had naysaid the attempt, apparently not wanting to give up his star editorialist. He told Cash that he was making a mistake to take the Guggenheim and quit the News. (Source: W.J. Cash: A Life, p. 182)

Last

Letter From W. J. Cash to J.W.

Before Leaving

(Re-printed in W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet by Joseph L. Morrison)

(ca. May 1, 1941)

Dear Dad:

This leaves me still ten dollars behind on last month, but I've been so hard run that I couldn't lay hands on any money. I'll get $200 for the speech in Texas, and since it is on the direct rail route to Mexico City, it is just so much picked up. That still doesn't solve the money question fully—of paying my debts and getting some fairly decent clothes before I leave here. I'll have to have dress clothes, of course, for that speech. I hope to write some stuff I can sell this month. But if not I can get some money from Knopf, though I prefer to leave that alone for the present—as an ace in the hole.

I am sorry that you have felt so lonely. We had planned to come up there this week end because we knew you would feel that way. But the opportunity developed for us to go to Chapel Hill and it is Mary's last chance to see her mother before we leave. Mrs. Ross won't get here until sometime in June, after we are gone.

I know you don't like me to go off to Mexico on this Fellowship. I know also that it has some risks, and that I shall have to work in order to make myself financially safe at the end of the year. More than that, I hate to go away and leave you feeling as you do, with everybody else pretty far away from you, too. I thought about it a lot, and was sometimes tempted to turn it down. But it didn't seem to make good sense. I owe it to myself, to you and mama, to Mary, and the whole family to go ahead and try to have as good a career as I can, and to have been a Guggenheim Fellow gives you a long shove ahead—to say nothing of giving me a year free for writing and seeing what I can do toward achieving complete independence. I failed at that once before, but it was the terror of my economic condition that mainly paralyzed me. This time I'll have fair security for the year. And more than that, I now have reputation enough to make it easier for me to get a job if I need and want one. To ask for a job as one who is unknown, broke and down and out, who hasn't had a job for several years, and to ask for one as a Guggenheim Fellow with a solid record as an editorial writer and as the author of a book which has made a great reputation—these are very different things. And I don't think you need to worry on that score. There wasn't any prospect of advancement here and not much of more money than the shabby salary I have been paid. So I thought it best to make the decision and go ahead.

If war breaks out we shall probably leave Mexico and come back to the United States, and that seems very likely. However, if I could get a job as a correspondent I might stay down there awhile, though I might send Mary back. That all remains to be seen, however. We will have round trip tickets, so we can be sure of getting away at any time we want to. And in any emergency, I can always fly into Charlotte in about fifteen hours for little more than rail fare. I don't like flying in general, but it is no more dangerous than the trains or ships and a darn sight less dangerous than an automobile.

Tell Mama not to imagine things about earthquakes. Mexico City has slight shocks practically every day, but the heavy stone walls are built for it. The reason for these shocks is that the city used to be an island—a marsh, rather. And the ground is still soggy and shifts about easily. But this same sogginess keeps the city from suffering from the genuine earthquakes which sometimes rock other parts of Mexico. The city has never had a serious earthquake since Cortez entered it in 1521. And she must not imagine, either, that it is wild country. It is in fact a city of nearly a million and a half people, modern in its sanitation and as well policed as any city of the United States. There are sometimes riots at election times but we have them, too—not to mention our labor riots. All you have to do to be safe is to stay out of the crowded districts at election time.

Mary's mother is related to Mrs. Josephus Daniels, who is Ambassador down there, and Jonathan Daniels, son of Josephus, is my good friend, and so we will be well looked out for down there. Incidentally, Jonathan Daniels, Thomas Wolfe, Paul Green, and myself are the only four North Carolinians who ever won a Guggenheim Fellowship in the field of literature.

Well have to leave here Saturday morning, May 31, to be in Austin on June 2 when I am to make the speech at the University. I had promised Bill Dowd to stay here until the end of that day, and he had made his arrangements accordingly. If I possibly can we'll leave here Wednesday and come up to Shelby until Friday night. If not we'll come the Sunday before and again on Thursday afternoon. I feel bad that I can't stay longer, I wanted to, but things have me crowded so that I can't.

We see you next Sunday.

Love to Mama,

Love,

WILBUR

And thanks for remembering my birthday. I don't particularly mind them anymore.

1 Cash was then paying $30 monthly toward his parents' upkeep out of a weekly paycheck of $50

2 On Saturday, May 3, 1941, Mr. and Mrs. W. J. Cash were at Chapel Hill, where he addressed a banquet of the N. C. Scholastic Press Institute. Mary Cash's widowed mother, Mrs. Joseph Russell Ross, was then employed as housemother in a Chapel Hill fraternity house.

3 Cash refers here to his situation on joining the staff of the Charlotte News on October 18, 1937.

(Notes by Joseph L. Morrison from W.J. Cash: Southern Prophet)

See photos of original three page letter at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library.

The original April 24 invitation by University of Texas president Homer Rainey to deliver the commencement address in Austin, to which Cash refers at the beginning of this letter, may also be viewed at The Rare Book Room.

Excerpt from Last Letter from

Cash to Alfred Knopf,

May 20, 1941

(Reprinted from W. J. Cash: Southern Prophet, p. 122)

My plans at present are to use the first four months in Mexico in working on that novel I have in mind. The material is already pretty well in hand, and in that period I think I can settle the question of my ability to do that kind of thing. If I find the answer is that I can't, I'll switch over to a nonfiction project, and probably come back to the United States to work on it. I already have the permission of the Guggenheim Fellowship to make the change when and if I desire to do so. I have number of things in mind tentatively, but the time to discuss them will of course be when and if I find the switch desirable.

See last known letter from Knopf to Cash, dated May 26 at The Rare Book Room of the Wake Forest University Library. "The Item" to which Knopf refers is presumably what, if any progress Hermann Deutsch had made on his biography of Huey Long. Cash had informed Knopf in September, 1940 that he would like to do a non-fiction work on Huey Long while working on his novel. Knopf informed him that Deutsch had already been under contract with Knopf "for several years" to do such a book and might still be planning to complete it and that he would check on it for Cash. Apparently, Cash still maintained the interest in May. (Deutsch in fact published with Doubleday The Huey Long Murder Story, but not until 1963; Deutsch had published The Wedge, A Novel of Mexico in 1935.) Knopf concludes with an ameliorative comment on his disappointment in the sales of the book, that even so few as 2,500 copies sold would provide "a step up" to Cash in the world of letters given all of the favorable press. Cash was never disheartened by the lack of sales at that time, indeed, had never expected a book of that kind to sell very well, and realized, as evident in the May 1 letter to his father, that the critical praise was the important thing to nurture his writing reputation and thereby give his novel-to-be a chance to be read widely. In fact, as is plainly expressed in correspondence to Knopf in August, 1940 right after mailing the finally completed manuscript, his "heart" had long been in writing a novel on the South and had gone out of writing Mind after the mid-thirties--after which time most of it was written.

Prior to leaving, Cash also toyed with the notion of becoming a war correspondent should the fiction not flow or should the United States become officially involved in the war. In that event, he had in mind sending Mary back to North Carolina and taking the Pan Am Clipper to England or Portugal; State Department clearance was afforded war correspondents in those days though on a secondary priority to diplomats and military observers. (See National Geographic, August, 1941, pp. 262-263)

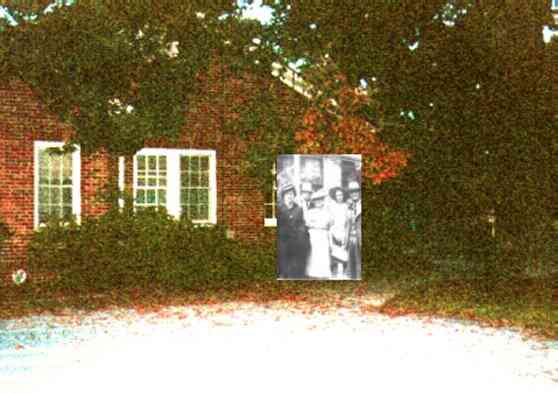

South side of 203 North Morgan Street, facing Sumter, where last photograph of Cash with his family was taken by Charles H. Elkins on May 25, 1941. After the departure of Mary and Wilbur that last Sunday, Nannie confided in her family that she believed she would never again see her eldest son alive. (The splash of autumn color overhead in the 1998 photo above is completely natural.)

Nannie would die August 12, 1959, J.W. on November 16, 1964, Mary on September 4, 1980, and Bertie on July 18, 1987