![]()

The Charlotte News

Saturday, October 1, 1955

THREE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports from Denver that the President, according to his physicians, had enjoyed "a good night's sleep" again the previous night, was "relaxed and comfortable" after signing two documents which had returned him to the helm of his Administration. The documents had appointed 117 foreign service officers. Chief of staff Sherman Adams had arrived in Denver to lay the groundwork for the President's gradual return to greater personal activity. The President's temperature was normal, his pulse and blood pressure continuing to be stable and satisfactory. It provides once again his breakfast menu, in case you wish to copy it down. His hospital bed had a motor which enabled the nurses to lift or lower him by pressing a button. Bet you wish you had one of those. Unlike most hospital beds, it could be lowered to a point where the President could turn and place his feet on the floor. Physicians were contemplating that he would remain in the hospital for about a month before flying back to his farm in Gettysburg for another month of convalescence, and during that latter period, he would be able to hold necessary conferences, absent any complications in the meantime. Whether any enterprising Air Force officer would undertake to order $5,000 worth of furniture from Jordan Marsh Department Store for the President's hospital room remains to be seen.

In Paris, Premier Edgar Faure and Foreign Minister Antoine Pinay had determined to recall the entire French delegation from the U.N. meeting in New York, following the previous day's General Assembly vote to debate France's actions in Algeria. The French delegation had walked out of the Assembly the previous night, after it had voted 28 to 27, with five abstentions, to upset a steering committee decision, and place the issue of Algerian independence on the agenda, strenuously opposed by the French. A French delegate, when asked, had commented that France might depart the U.N. permanently. There was no immediate word, however, whether the action this date meant a permanent withdrawal or was intended only to enforce French protests against the Assembly action. Britain and the U.S. voted with France against the debate on the ground that Algeria was part of France and thus the U.N. would be intruding on France's internal affairs. M. Pinay told the Assembly, in the wake of the vote, that he would consider any action taken by the Assembly on Algeria to be null and void, then walked out with the delegation.

In Algiers, it was reported that at least a dozen French soldiers and nationalists had been killed the previous day in scattered clashes throughout the country. The outbursts occurred as the U.N. vote had taken place, with there being no immediate indication whether the vote would help bring temporary cessation to the violence in rebel-infested areas of Algeria or whether it would incite new disorders. Most of the previous day's clashes had occurred in the Constantine area of eastern Algeria, the chief rebel stronghold for several months. Algeria was ruled as part of Metropolitan France and the French Government leaders had said that they would maintain the present control over the area at all costs.

In Rabat, Morocco, Sultan Mohammed Ben Moulay Arafa departed his palace this date and flew into exile in Tangier, naming a cousin to "look after affairs relative to the crown." He had quit, though not formally abdicated, the throne after holding out for weeks against French pressure to remove him as a preliminary condition to establish peace and a measure of self-government to the protectorate. The Sultan stated in a broadcast announcement that he was leaving the capital for an unlimited period of time in the interest of peace and unity for Moroccans. He had flown to Tangier in a French military aircraft. Technically, Tangier was part of the Sultan's domain, though actually under international administration, with neither the Sultan nor the French having any direct authority there.

In Tokyo, Japan had sent wave after wave of troops, tanks and big guns surging across Meiji Plaza this date, in a proud first anniversary display of its re-established armed strength. Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama and Diet leaders, plus U.N. military observers, viewed the parade. U.S. Ambassador John Allison, U.N. commander, General Lyman L. Lemnitzer, chairman of Japan's Joint Chiefs, General Keizo Hayashi, and other military officials also viewed the parade. Conspicuously absent was Emperor Hirohito or any member of the imperial family. Ships of the fledgling Navy were on display in Tokyo Bay, and the Air Force had planned to fly 111 of its planes over the city, but the flights had been canceled.

In Eli, Minn., iron miners dug steadily 1,300 feet underground this date, but were holding out little hope that they would find alive a fellow worker who had been trapped for more than 32 hours by a mine shaft collapse. Two of the three miners who had been initially trapped had been brought to safety the previous night, both unharmed. The remaining trapped miner was married and had two children. One of the two rescued miners said that the sound of the drilling had been their only hope because they had no chance of escape, as the tunnel had been filled with dirt and mud, and they could hear the sound of the timbers giving way. Their air had become short, but they could hear the pipe the drillers were sending to them coming through and when they turned on the compressed air through that pipe, they thought it was the end as it sounded like another collapse by the hissing all around them. They then had voice contact with the surface for the first time and knew that help was on the way, but still did not know it would reach them in time, as rocks continued to fall.

The News announced this date, as continued on an inside page, the resignation of J. E. Dowd as its vice-president and general manager and that Brodie Griffith, previously executive editor, would become the new vice-president and general manager of the newspaper. Cecil Prince, chief editorial writer for the previous several months, would become associate editor in charge of the editorial page. Publisher Thomas L. Robinson expressed regret that Mr. Dowd had decided to retire from the newspaper, with which he had been associated for most of his life, saying that he was one of the most able newspapermen that he had ever known, "a gifted editor, one of the South's best, and equally talented as a newspaper business executive." He indicated that Mr. Griffith had been with the newspaper for 32 years, first as the state editor, then as managing editor and most recently as executive editor, was recognized as "one of the South's most able newspaper executives". He also expressed good fortune in having "young, able" Mr. Prince assume responsibility for the editorial page, having come to the newspaper a year earlier from the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville, and since having shown his outstanding ability as an editorial writer. He had attended Pasadena Junior College in California before graduating from UNC, after which he worked initially as a reporter for the Greensboro Record.

In Charlotte, the heaviest rainfall since 1944 during a 24-hour period had been recorded this date, with 4.84 inches falling, a 24-hour rainfall of 6.59 inches having been recorded in July, 1944, with more in such a concentrated period recorded only seven times earlier since 1879. An electrical storm had come through the area, knocking out power for brief periods in some sections of the city, causing the postponement of two city and nine area football games. This date, the forecast was for rain by mid-afternoon, with cloudy skies and mild weather giving way to clearing skies this night. On Sunday, it would be fair and rather cool with the morning low of 55 and the high, 76. The high this date would be 80, seven degrees lower than the high of the previous day, with the low having been 66, and the low for Monday forecast to be 52. Don't leave your home without your rubbers.

Helen Parks of The News reports on the Western North Carolina Methodist Conference taking place during the week in Charlotte, indicating that new pastors were expected to be appointed to at least seven Methodist churches in the Charlotte area the following day at the close of the conference, listing those new pastors.

Emery Wister of The News

reports from Biltmore Estate in Asheville that director Charles Vidor

had scowled at the low-hanging clouds, saying that he guessed they

would have to shoot those "horses' tails", ordering that

the cameras and lights be moved into a stable, rather than shooting

an outdoor scene as planned for the filming this date on "The

Swan"

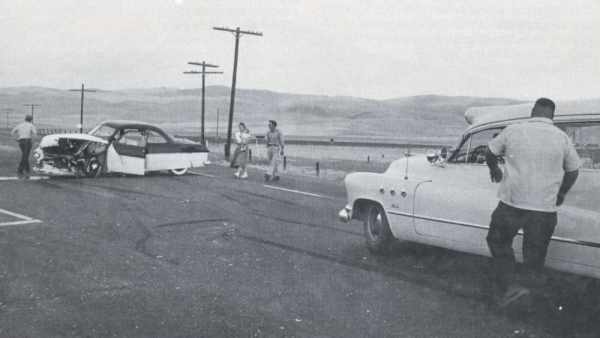

We suppose, because of the front

page placement of the stories about the Asheville filming and the

changeover in staff, that there was no room left to present even a

paragraph about the death of actor James Dean in an automobile

accident the previous afternoon at around 5:30 at a lonely, desolate

intersection of State Highway 41 and U.S. 466 in tiny Cholame, Calif., near Paso Robles. Young Mr.

Dean, 24, had died instantly of a broken neck when his Porsche 550

Spyder collided with a 1950 Ford turning left across his path from

Highway 41 onto its continuation to the left off the junction, not

yielding the right-of-way to the Porsche traveling along Highway 466. Mr. Dean, who had just

finished filming "Giant", his third feature film, with only

one, "East of Eden", having thus far been released to the

public, the second, "Rebel without a Cause" set to be

released later in October, had been driving the low-slung, silver,

aluminum Porsche, purchased only a week earlier to replace his

stouter Porsche 356 Speedster, with the smaller, aluminum car primarily

intended for racing, which Mr. Dean was planning to do with it, on his

way to Salinas at the time, traveling with his German mechanic, who

survived the accident, albeit with injuries. The driver of the other

car, 23, from nearby Tulare, Calif., walked away from the accident

unharmed. Just why the newspaper, given its recent stress on

automobile safety, the need for improved personal safety checks of

vision and equipment, and stricter enforcement of traffic laws, would

not print the wire story on an accident of this type as a public service, a warning

especially to younger drivers to maintain their attention to the road

ahead at all times, especially at the time of day of changing light

conditions with the sun low in the sky, is baffling, as no word of

the accident would ever appear in the newspaper this date or in the

ensuing days. Nor would it be mentioned in the Charlotte Observer.

Both the Raleigh News & Observer and the Durham Morning

Herald carried short stories inside the newspapers on the death, as did the Hendersonville Times-News, on the front page. The story had made the front page of the Macon News in Georgia, replete with a photograph, as Macon knew in advance their bacon, and, of course, as expected, the front page of the Los Angeles Times.

There was obviously no bias against Hollywood generally by The

News, as witness the front page this date, and many other such

Hollywood stories appearing on the front page on a fairly routine

basis. Perhaps, it was simply the case that Mr. Dean, at the time,

was not that well known as an actor, with his subsequent film stature

having been established with the younger audience primarily by his

second film, and, to a lesser degree by "Giant", to be

released in October, 1956. It would not be for another year until his status

would grow to mythical proportions in the aftermath of his death and

the release of the subsequent two films. It is ironic that his fame

had never really been established to any degree during his lifetime,

though he had been recognized by Hollywood for his acting talent

displayed in "East of Eden". Prior to that picture,

however, he had been engaged only in sporadic television work and theatrical work in New York. He was

seen as a young, rising star, but not yet as a full-fledged star in

Hollywood, certainly not to the mythical proportions which, in death,

he achieved. One report, in the Los Angeles Times of the

following day, indicates that he had a premonition of death at a

youthful age and was hurrying along in life to beat that premonition.

Whether that was true or just postmortem poppycock from a press agent

to stimulate a myth, we have no idea. In any event, it might be noted

that there was a 1950 Ford, as well as a couple of nearly indistingushable 1949 and 1951 models, among the cars quickly departing the scene

As we have indicated previously, we

once had occasion many years ago to visit the location of the

accident. There is nothing really there, save a small memorial in the

midst of a parking lot for a hamburger stand a couple of miles down the road. The hamburgers,

however, were pretty good. We had no accident at the intersection, but maintained a

coign-of-vantage for any 1950 Fords heading our way out of the

twilight. Stranger things have happened... It was on the same trip

south, returning on the Pacific Coast Highway from San Diego, the same day that the first four CD's of that band had been released, to which we were listening on the playback device at the time, when,

as also previously recounted herein, we encountered in Malibu a

driver coming toward us, who had just crossed the center line into

our lane, about two car lengths away, affording us no more than a

split-second to react to the right and avoid what, undoubtedly, would

have promised, at a combined head-on speed of no less than 150 mph, a

certain joinder with the great beyond into which Mr. Dean was, this

date in 1955, somewhere. Maybe the stop at the intersection in

Cholame less than 24 hours earlier had served to remind us in advance

to pay attention at all times to the roadway, to that sign up ahead,

for the least expected

Perhaps, some enterprising reporter

might have thoughtfully inquired of Sheriff H. C. Strider in Sumner,

Miss., whether he thought that Mr. Dean, also, might be somewhere

On the editorial page, "J. E. Dowd's Influence Will Continue" indicates that Mr. Dowd, the former editor of The News until 1947, when Mr. Robinson had, along with a group of investors, including Mr. Dowd, taken over ownership of the newspaper from the Dowd family, where it had resided since five years after the newspaper's founding in 1888, would continue, despite his retirement as general manager of the newspaper, to have influence by virtue of the newspaper's "living thread of tradition." Mr. Dowd had served in two major roles, first as the editor, then as a key figure in the managerial aspect of the newspaper, distinguishing himself in both fields. He had emerged as a journalist in a period of "intellectual, social and political ferment."

It says that his editorials had reflected the excitement of the times but never the frenzy, that he had asserted truth and unveiled illusion with a firm and practiced hand. He had helped to take reform from the level of emotion to the plane of thoughtfulness.

After the newspaper had exposed shocking deficiencies in the care of mental patients at state hospitals in 1942, from the participant-observer accounts of Tom Jimison, he had been largely responsible for persuading the State to undertake measures to correct that situation. His vigorous editorials had helped bring about reforms in the State penal system after two mistreated black prisoners had lost their feet in a prison camp near Charlotte. His editorials had taken on the slums of Charlotte, as reported by Cam Shipp in 1937, and he had campaigned successfully for minimum housing laws to reduce that blight. He had also editorialized in favor of realistic city planning and had been an early advocate of an adequate auditorium to meet Charlotte's cultural needs.

"His writing technique—lively, biting, often artfully tipped with subtle humor—is one of great originality. It can also be said that when attacking an editorial subject, he knew precisely when to use the fly swatter and when to roll up his heavy artillery."

It concludes that the Dowd influence had lasting qualities which would never be completely lacking on the editorial pages.

As it notes, the masthead on the editorial page now listed a different lineup, with Brodie S. Griffith as the new general manager and Cecil Prince as the new associate editor, with Tom Fesperman, the new managing editor.

As Mr. Prince was fairly new to the newspaper, he may have confused some of those earlier editorials, at least those published between November, 1937 and May, 1941, with those of Mr. Cash, but that's alright as Mr. Dowd was retiring, though he would join the Observer thereafter as business manager through his death in March, 1966, and Mr. Dowd's older brother, W. C., former publisher of the newspaper, had hired Cash, and Mr. Dowd had ultimately given Cash credit in December, 1938 for those "masterpieces" for which some had given him, by his own account, undeserved credit.

"The Middle East: Tightrope for U.S." indicates that the President's illness had obscured international issues during the week in which tension had been rising steadily nevertheless, particularly in the Middle East, adding to cold war turmoils in Europe and the Far East.

On August 30, Secretary of State Dulles had expressed fear of an arms race in the Middle East, and that had taken on concrete form with Egypt's indication that it would purchase arms from Russia's Polish satellite, including jet bombers, heavy tanks, heavy artillery and naval craft, potentially upsetting the already precarious military balance in that region, unless the U.S. or Britain countered with a similar sale to Israel. If the balance were to be maintained by increased armament of both countries, the inevitable renewal of the Egyptian-Israeli border disputes could quickly occur, turning skirmishes into major conflicts.

There was also a smoldering revolt in Algeria, in which the U.S. had sided at the U.N. with the rejected French view that self-government demands of Algerian nationalists were an internal French problem, as Algeria was technically a part of France and should not be considered by the U.N. That view had produced harsh criticism of the U.S. from the Arab-Asian bloc, accusing the U.S. of supporting French colonialism and rule by force in Algeria, causing the U.S. to have to walk a middle course, which, as in the Egyptian-Israeli dispute, did not really exist. There was only the problematic alternative of either supporting France, the NATO partner, or supporting the aspirations of the nationalists, aiming toward independence.

The peace plan to halt bloody uprisings against the French in Morocco had been disrupted by the inability of the French to agree among themselves, with the Sultan who had been installed by the French as a stooge having resisted pressure to resign and make way for a regency council, as favored by Premier Edgar Faure and his Government, as a means to answer the nationalist demands for greater home rule. The alternatives in Morocco were as bleak as those in Egypt, for if Premier Faure forced the Sultan's ouster, his own Government would be in grave danger of falling as a result of the angry reaction of French commercial interests in Morocco, and if the Sultan remained, it would only be a matter of time before the nationalists would renew their revolt. (The story this date on the front page appeared to report of resolution of this dilemma, with the Sultan having voluntarily entered exile in Tangier.)

It indicates that unless the Middle East peace was preserved, all of the crises would potentially come under the influence of Communism. Nothing was to be gained by Western participation in a Middle East arms race, with the simplest move being to announce a firm Western guarantee of frontiers of Israel and the Arab countries, the best insurance against aggressive use of the new Egyptian arms, also placing responsibility on Egypt and Russia for any trouble which might develop.

In Algeria and Morocco, U.S. support for the French, either within or outside the U.N., could not save the peace, as the French had to yield to the desire of the nationalists for greater freedom, while at present, it was only yielding to its own internal bickering.

"May All Their Slips Be Yellow!" provides tribute to newspaper delivery boys, who had the task of delivering the news in eight-point type to a hundred porches daily, through all types of weather, in daytime and cloak of darkness, and then having to go around once every week to collect their wages from the customers.

It indicates that the job had evolved from earlier days in at least one important respect, that modern circulation managers frowned on the practice of folding papers and aiming them at a front porch from a speeding bicycle, such that the practice had now virtually disappeared. But most aspects of delivering newspapers had remained the same, with the frustrating inserts, the Thursday food sections and Saturday comics, which had to be folded, sometimes in the rain, and inserted behind each door, while dogs snarled and yet had to be treated kindly so as not to rile the patrons. (We thought the food section appeared in the Wednesday editions. Don't they pay attention to their own newspaper?)

Several newspaper boys had grown up to become President or publisher of a newspaper, but during the actual career of a newspaper boy, they got their due only during National Newspaper Week, one day of which was set aside by the press in each state as Newspaperboy Day, that being the present date in North Carolina. It indicates that the newspaper bowed to its carriers with gratitude and no little pride.

You're welcome. We do it for free, and for every damned day since October, '37. We were here when you were in grade school. Oh, we know, we're behind a month in deliveries right now, but at these wages, what the hell do you expect? Anyway, we have to run along now, as we wish to see that new television show tonight, "TV or Not TV", even though we probably are going to miss the bulk of the first episode, while rolling up our newspapers for throwing on doorsteps Monday afternoon, and have to rely on accounts told by others to fill in the blanks, while awaiting later the repeats, maybe next summer. Why, you may ask, are we busy rolling up newspapers on Saturday night for distribution on Monday afternoon? Because some mental case, a boyfriend of one of the young nymphs of "Papa" Peron, who contends, without portfolio, that we supported El Presidente's ouster and therefore..., claiming copyright to this date's newspapers, stole the bulk of our bag's worth and refused to give them back, and so we guess it's mostly "not tv" for these slings and arrows of missed portions. Meanwhile, we figure on entering this contest, as, little do they know, we have these suckers beaten by 18 years.

George Beasley, Jr., writing in the Montgomery Herald, in a piece titled "The Decline of Whistling", asks what had become of whistling, that the only thing remotely resemblant to it was the happy sound of the frayed phrases of "Davy Crockett" or some other current jukebox fad.

He wonders whether the complexities of the modern world had frozen man's lips so that he could no longer pucker up for whistling, whether happiness had been so depleted that he no longer even had the urge to do so.

Whistling, he concludes, with laborers' work having been taken over by machines and the noisy motors thereof drowning out the work songs, was now gone. He hopes that the reason for it was that there were so many things to think about at present and not because men were not as happy as they once were.

He might have noted that following the Emmett Till murder by a couple of humorless reprobates in Mississippi, whistling will undoubtedly be a harder sell in public henceforth, with no humor in that observation intended. And not even "Standing on the Corner" of the following year will likely revive it to any significant degree in an increasingly humorless age of man, where everything must be taken literally, even when issued by 14-year old boys, at least when confronting semi-retarded, idiotic "adults".

Drew Pearson indicates that while the President was recovering, things continued to go forward in various parts of the world and he summarizes the most important of those events. Secretary of State Dulles had been so upset at the concessions made by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer to the Soviets in Moscow the previous month that the Chancellor had offered to fly to New York during the week to confer with Secretary Dulles and straighten out things, but the offer had not been accepted, and instead the West German foreign minister had flown to New York. Secretary Dulles and Prime Minister Anthony Eden were also rubbing each other the wrong way, with Mr. Dulles suspecting the latter of sliding over toward the Russian view regarding Germany, while Mr. Eden was so sore at Mr. Dulles that he hardly communicated with him.

In Greece, there was trouble with Turkey, with the possibility that the strongly pro-American Government of Premier Alexandros Papagos might be overthrown. The latter was ill—dying only three days hence—, and meanwhile, there was American refusal to support Greece with regard to Cyprus and in its quarrel with Turkey, producing a wave of anti-American feeling. Secretary Dulles had added to the ill feeling by sending a note to Greece, in which he expressed no word of sympathy for Greek losses during the Turkish riots. Those two countries were the backbone of the anti-Communist U.S. alliance in the Near East, as together they were positioned athwart the Dardanelles and Russia's entrance to the Black Sea. Billions of U.S. dollars had been invested in the defenses of those two countries during the Truman Administration, in an effort, as part of the Truman Doctrine, to block Russia. If they continued their quarrel, those defenses could be neutralized, or if the existing Greek Government fell, a neutralist Greek premier would probably take office and turn to Russia for support. It represented the most serious and urgent crisis facing the State Department, but Secretary Dulles, concentrating on Germany and the shortly upcoming foreign ministers conference in Geneva, had done little about it.

In addition, the U.S. ambassador in Egypt, for weeks, had been cabling the State Department warning that if the U.S. did not sell arms to Egypt, it would buy from Russia, informing Secretary Dulles that the Soviets had offered Premier Abdul Nasser 100 million dollars worth of tanks, artillery, and infantry equipment any time he wanted it.

Joseph Alsop indicates that in the wake of the President's heart attack, RNC chairman Leonard Hall was persisting in his insistence that the President would run again in 1956, with his subordinates swearing that the chairman meant what he said, giving all sorts of elaborate reasons why his hopes would turn out to be well-founded, provided the President made the good recovery for which everyone was hoping. Among other Republican leaders and among the party rank-and-file, everyone was automatically repeating the statements by the President's heart specialist that, theoretically, he would be fit to run again provided his recovery progressed satisfactorily, opinions which were becoming more widespread with the improvement of the President's health.

Mr. Alsop finds, however, that it was unrealistic and shocking to continue the pressure on the President to seek another term. The Republicans had considered it wicked for President Roosevelt to have sought a fourth term in 1944 when he was not in peak physical condition. Yet, when the President had accepted the nomination in the summer of 1944, he was no more than a little wearied by the burdens of the office, and, contrary to reports, he had no warning of any major health condition on the horizon, when he suddenly keeled over at his desk in Warm Springs of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945. He had been certified by his physician as in good shape and at the time, was more than three years younger than President Eisenhower would be in 1956.

Aside from that parallel, which he posits should be decisive, there were other practical reasons why it was unrealistic for Republicans to pretend that President Eisenhower would go forward after his heart attack as if it had never happened. It had been an open secret before the attack, that First Lady Mamie Eisenhower and their son, Major John Eisenhower, were bitterly opposed to another term. Nevertheless, because of the prodding by chief of staff Sherman Adams and Mr. Hall, plus everyone else around the chief executive, he had pretty much decided that it was his duty to "finish the job". But all of that had now changed with the heart attack.

No one would now dare pressure him to run and, suggests Mr. Alsop, it was no one's duty to run for the presidency after a heart attack. The Army, in which the President had been trained, had a strong tradition that a commanding officer whose health was impaired to any degree had a positive duty to stand aside in favor of another taking command.

He suggests that such insistence by Republican leaders was a symptom of the party in disarray, that the leaders had no idea which way to turn without the leadership of the President, but that such surrender to panic was ludicrously premature. The Republicans could run, assuming nothing catastrophic were to happen in 1956, on peace and prosperity, twin engines for victory, without much else necessary for a party platform. The Republicans had now come face-to-face, in light of the President's illness, with the terrible folly of their own self-indulgence in reliance too much on one man. The proof of their folly had come in the 1954 midterm elections, when the Republicans had lost both houses of Congress.

Mr. Alsop concludes that there was no reason why Republican leaders could not now do what they should have done before and find an acceptable candidate who could be presented as a true Eisenhower man for a party which the country believed was truly an Eisenhower party, the only requirements which the Republicans had to fulfill to regain their former confidence. He adds that they were not impossible requirements to fulfill.

Frederick C. Othman indicates that the one person in the world who would not want anybody to feel sorry for him was Glenn McCarthy, the multimillionaire. Recently, he had been strolling into the Shamrock-Hilton Hotel in Houston, which he had built as a monument to himself, taking a long look at his oil portrait in the elevator lobby, a portrait which appeared to be of a far younger man than its subject at present. The Shamrock had bankrupted him, but he did not look sad, giving the "old McCarthy bear hug" to numerous citizens in the hotel which had ruined him, bubbling over with tales of his current Bolivian adventures. He was anticipating becoming a millionaire all over again and no one in Houston was willing to bet against him.

He had gotten in touch with a New York dealer in oriental rugs, who had previously sold him many rugs in more liquid days, and the merchant developed a syndicate of his friends who invested two million dollars in a prospective oil pipeline in Bolivia, near the Cran Chaco, with full confidence that Mr. McCarthy could once again work his magic, and the latter was now rounding up equipment and a crew for piping oil out of the jungle.

Mr. Othman says that he was now paying $16 per night to sleep in the hotel which had bankrupted Mr. McCarthy and that if he stayed there very long, it would also bankrupt Mr. Othman, who describes it as a luxurious room, replete with a garbage disposer.

A letter writer of the Southern sales division of B. F. Perkins & Son, Inc., indicates that since his previous letter to the editor, regarding the tariff reductions affecting the textile industry, he had received some figures from the head of the statistical division of the Tariff Commission in Washington, through the office of Congressman Charles Jonas, showing that in 1955, the figures for only the first half of the year being available, the U.S. would export to Japan 33.9 percent less raw cotton during the current year, when extrapolating the figures for the first half also for the second half, than in 1950. It would export to Japan 41.5 percent less textile machinery in the current year than in 1953. He thinks those figures were appropriate for both textile machinery manufacturers and farmers to consider. The volume and dollar value of Japanese imports of cotton cloth alone had increased yearly, except for 1951 and 1952, to a point where, conservatively, the U.S. would import 422 percent more Japanese cotton cloth in 1955 than in 1950, not including imports of cotton carpets, rugs, velveteen and damask, which amounted to 66.46 percent of the total cotton goods, according to figures obtained from the Commerce Department.

Those imports of velveteen are likely to take off even higher with the advent of the velvet Elvises. But, obviously, you do not have the slightest idea of that of which we speak, but you may, by the following summer. Add to that, the velvet James Deans by that point, and Japanese industry in that department may be booming beyond all belief. You may even see, in the poor taste department, some velvet representations of the crash scene in Cholame. Whatever sells, when it sells… When it doesn't, hold a fire sale during Bargain Days.

Whether, incidentally, the surname of the driver of the Ford was Turnupseed, Turnipseed or Turnispeed, each of those variant spellings having appeared in the wire service stories this date, we know for a fact, don't we, that anyone with that kind of name had to be CIA or MI6, or possibly Stasi, and that the whole "accident" was a Government plot to hush up Jimmy, as he was about to reveal the revelations which would have led inexorably to other revelations, which would have caused the whole bloody thing to have blown up in their faces.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()