![]()

The Charlotte News

Saturday, December 21, 1946

THREE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports that Governor-elect Eugene Talmadge of Georgia, set to take office in a few weeks, had died in Atlanta at age 62. He had suffered a stomach hemorrhage in Jacksonville on October 4 and had been continuously confined to the hospital since November 29 after having appeared to recover, suffering finally from acute inflammation of the liver cells, possibly caused by a transfusion. It would have been his fourth non-successive term as Governor.

It being the first time in the history of the state that a Governor-elect had died before taking office, a bitter fight lay ahead to determine who would be his successor. The State Constitution appeared to require that the current Governor, Ellis Arnall, remain in office until an election could be held four years hence. But the Talmadge forces promised an effort at impeachment should Governor Arnall not surrender the office once the Legislature appointed a successor.

Ultimately, after a stormy period in which both Governor Arnall and Mr. Talmadge's son and campaign manager Herman Talmadge, selected as the successor by the Legislature, assumed the office, the most recently elected Lieutenant Governor, Melvin Thompson, was sworn in as the legitimate successor by decision of the Georgia Supreme Court. A special election in 1948 would be held and Herman Talmadge would win.

At 4:20 a.m., a violent earthquake, possibly the worst ever recorded, shook the Honshu coast of Japan, from Shimoda to Kochi on Skikoku's southern coast, causing six severe tidal waves in its aftermath, beginning at 5:30, affecting more than 50,000 square miles of Japanese territory. Some waves were ten feet in height. Kushimoto, a fishing town of 10,000 people, was wiped out by seven-foot waves. Fire destroyed a third of Shingu on the east coast of Honshu. Water was three feet high in Osaka, Japan's second largest city, where 14 people were reported killed. Nearby Kyoto and Nara, however, escaped serious damage.

At least 500 people had been killed and 612 injured, with 43 missing. Some 28,000 homes had been destroyed and 500 fishing vessels were lost. Only one Allied casualty was reported, a missing British soldier. The fact that the quake had its epicenter under water had prevented greater loss of life.

In Northern Indochina, French troops had suffered heavy casualties after advancing in two sectors, losing a small garrison at Vinh by forced surrender to Vietnamese forces under former guerilla leader, now President Ho Chi Minh. The garrison was promised that their lives and property would be spared upon surrender. French troops, under continuous sniper fire, had reoccupied the Lanessan Hospital at Hanoi. Vietnamese forces had suddenly attacked the French garrison at Tourane the previous morning, resulting in heavy losses on both sides. The French maintained control of the Tourane airfield and mopped up surrounding areas. Relief efforts for Tonkin

Adding to problems of hunger in Europe, temperatures fell to zero in Germany, five degrees in France, and ten in Belgium. The mercury stood at thirteen in England. There were also sub-freezing temperatures in Nice and Turin. Torrential rains swept Italy, washing out two bridges at Toranto. In Germany, ice on the Rhine prevented barges loaded with coal, potatoes and grain from moving. Potato imports from the Russian zone to the British zone were stopped because of a frozen canal.

In New York, it remained unclear whether the previous day's passage "in principle" by the Atomic Energy Commission of the proposal for arms control was intended to eliminate the veto on punishment for violations of control of atomic energy. The reason for the problem was that the resolution, as amended by Canada, required conformity to the General Assembly resolution which left to the Security Council, with the veto, the final determination of arms limitation, including control of atomic energy. The Assembly had rejected several attempts to include a resolution to eliminate the veto on these issues.

George Meader, counsel for the Senate War Investigating Committee, was seeking authority from the U.S. Attorney to file contempt and perjury charges against Edward Terry, former secretary to Senator Theodore Bilbo, for Mr. Terry having refused to reveal to the committee the identity of the person who had received the $15,000 which had been provided him by a New York man to use against Mr. Bilbo in the Mississippi Senate campaign. Mr. Terry had claimed that he gave the money back to the man after the election, considered by the committee to have been impossible as the man had died before the time of claimed repayment. Mr. Terry then altered his story and contended that he was confused, but did not wish to disclose the recipient of the money.

The man did not wish to die at the behest of The Man. Perhaps, one cannot blame him.

Tom Fesperman of The News relates of the experience of a former Navy pilot during the war, Bill Smith, who was giving a ride to two girls going home to Charlotte for the holidays from Chapel Hill. As he approached Pittsboro, he saw a long line of backed up cars, attempted to go around, but was halted by a police officer who told him that some Navy fighter planes were having problems and were trying to use the road as a landing strip. He waited, the girls got out and walked around.

Soon, he saw one plane preparing for landing on the roadway, but also saw that it was going too fast for the approach. He saw the plane come closer and closer, finally so close that he decided it was time to bail out and hit the ditch. Just then, the wing of the plane passed over him and the other wing clipped the top completely off of his car. He was unhurt. So was the pilot. The girls had run away, were in a home taking aspirin tablets.

Dick Young of The News reports that the Police Chiefs of the City and County had implored residents to refrain from use of dangerous fireworks at Christmas, an historical problem in the county. Two years earlier, a five-year old boy had lost his hand in front of his sister while they played with fireworks.

Katherine Lawrence of Chester, England, provides her last in the six-part series of her impressions of Charlotte, stating that she had gleaned some odd notions during the war and its immediate aftermath of American men by having for the most part met only Texas farmers, men who claimed to have been possessed of vast estates. Some "dark gentlemen" told her that they were in camouflaged skins

Until arriving in Charlotte, she had never met a man from Main Street, such as the characters of whom Sinclair Lewis, with whom Britons were familiar, had written. She had been looking for Mr. Babbitt since she first had arrived on American soil. She had found Charlotte to be full of Babbitts, of an evening "sitting with ease in his shirt sleeves".

You cannot kid us. She had been reading Cash at some juncture.

Mr. Babbitt

Ms. Lawrence may have misperceived the American notion of the Babbitt, the go-getter, in his generalized form held in low esteem by the masses, even if, in truth, as she observes objectively, making up a good part of them, more so as time passed after the war.

So, whether in the end she was giving America a kind of polite English bird is not entirely clear. If so, that's okay. We do it to ourselves quite daily, and without so much British politesse

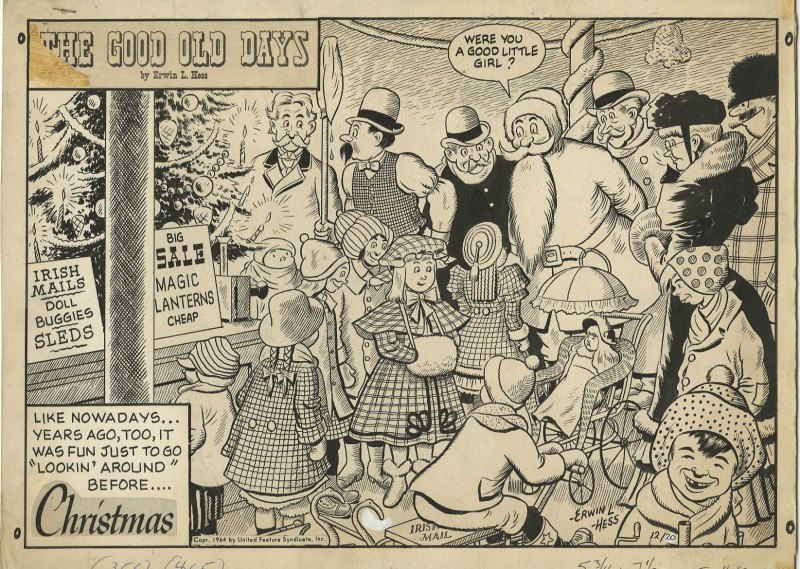

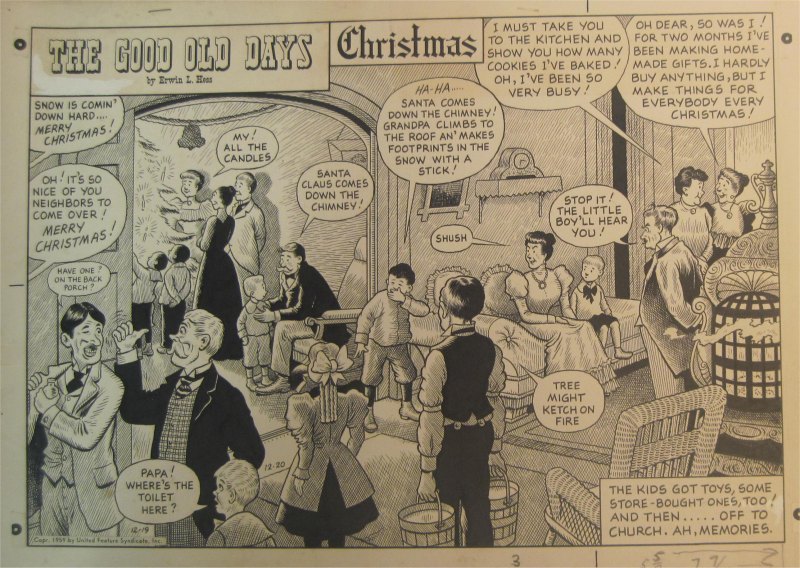

On page 7-B, cartoonist Erwin L. Hess provides a view of "Yuletide Memories for Moderns", something similar, we presume, to the two versions we supply below.

As far as the Empty Stocking Fund, it could be looking bad, kids. This gangster, of which a letter writer writes on the editorial page, may be the responsible party after all for having taken the Fund. But don't give up. We are still looking

On the editorial page, "The Defense of Deacon Bilbo" finds that the investigation of Senator Bilbo by the Meade Committee had adduced sufficient evidence to warrant his expulsion from the Senate based solely on his lack of integrity, not his ideology.

"The Unconventional Mr. Stassen" comments on former Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen having boldly cast his hat into the ring for the presidency in 1948, despite his fellow Republicans, Thomas Dewey, John Bricker, and Robert Taft, also prime contenders for the nomination, remaining mum. Mr. Stassen had also identified himself as a liberal, a stand which the Asheville Citizen had found to give him value as a rarity among Republicans.

In 1944, the late Wendell Willkie had managed to seize the nomination from the traditional Republicans, and it had to be accomplished by a storm, with a great showing of public support behind him. For Mr. Stassen to accomplish the same feat would be diffcult, made the harder by "the knowledge that any Republican with less than two heads can probably win the presidency in a landslide in '48"—as they would, in Chicago.

"Don't Forget the Winecoff" reports that the Winecoff Hotel fire tragedy, which took 119 lives two weeks earlier on December 7, was not a great topic of conversation. So it was gratifying that in Charlotte, officials were planning changes to the fire safety code in response to the fire and its report. One of the changes proposed was to mandate a night watchman on site for all buildings over two floors in height. Atlanta was considering requiring sprinklers and fire escapes.

The Legislature was also likely to pass a new fire safety code in the next session, but, ultimately, fire safety was a local matter and thus the promise of state action should not serve to postpone the action of Charlotte officials.

A piece from the Columbia Record, titled "The Misappropriated Banner", comments on a piece by Edward T. Folliard of the Washington Post, contending that the Columbians, Inc., were misusing the Confederate flag, a replica of which was hanging in front of their headquarters in Atlanta. But it did not look right as something alien had been inserted between the stars and bars, a jagged red streak, the thunderbolt insignia for the Columbians—which, to avoid association with Columbia, S.C., the Record insists on printing as "columbians".

It was a mistake surely to elicit the ire of every Southerner who venerated the memory of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. It then quotes from "The Conquered Banner"

The Record repudiates the flying of the flag, finds it to be sacrilege to those Southerners who had fallen 80-odd years earlier.

That's a nice way of putting it. We advocate burning the damn thing

Drew Pearson tells of the story that V. M. Molotov and Andrei Vishinsky had come to the U.N. Assembly meeting in New York, prepared to withdraw Russia permanently as a member. Secretary of State Byrnes and U.N. Ambassador Warren Austin had saved the day. A faction within the Politburo had argued against continued membership in the organization following the Paris Conference to determine the initial five post-war treaties. That faction believed intensely that the U.S. and Britain were plotting to form an anti-Soviet bloc within the U.N. and then use an incident in Iran or Greece as an excuse for dropping atom bombs on Russia.

Both Foreign Commissar Molotov and Prime Minister Stalin disagreed with this assessment and it was eventually agreed that the American and British attitude toward retention of the veto power on the Security Council would determine whether Russia would depart.

During the Politburo discussions, it was decided that Mr. Molotov would deliver a speech to the U.N. advocating multilateral disarmament to test the premise, that if the U.S. refused to go along with the proposal, it would be a signal confirming the faction's worst suspicions.

Former Senator Austin sensed the problem and immediately after the Molotov speech, called a meeting of the U.S. delegation. Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, Senator Arthur Vandenburg, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Adlai Stevenson were each in favor of supporting the resolution, while John Foster Dulles and Senator Tom Connally were tepid about it, as were some veteran advisers from the State Department.

Senator Austin then delivered a speech which did not answer Mr. Molotov but articulately supported disarmament. From that point forward, the Russian tone became conciliatory in private meetings, while Mr. Molotov continued tough talk at the Foreign Ministers Council meetings. Then Mr. Byrnes held a private conference with Mr. Molotov at which Mr. Byrnes reassured him that the U.S. stood firm on the continuation of the veto power. The following day, he agreed to the five treaties which had been worked out in Paris. Since that point, the Russian delegation had been cooperative, for the first time since V-J Day in August, 1945, apparently placing trust in the U.N. Charter formed in June, 1945.

Indicative of the new attitude, Mr. Molotov had issued an invitation to the press to come to Moscow for the next Foreign Ministers Council meeting in March. The Russians were considering allowing the U.N. to set up a Moscow office without censorship on what was disseminated. The Russians had also agreed to permit weapons inspection of its factories under the proposed disarmament plan.

The iron curtain, in short, appeared to be lifting. But enthusiasm was tempered by the fact that among the Russians suspicions of the West remained, even if the suspicions were somewhat in abeyance in deference to the need to rebuild Russia after the war, an exigency which required peace to meet.

A Mississippi contractor had testified that he had given Senator Bilbo four checks totaling $25,000 to help elect Wall Doxey to the Senate, and promised that they would raise even more money to help Mr. Bilbo be elected again should his election in 1946 be nullified.

Marquis Childs tells of Soviet support suddenly being withdrawn from the puppet pro-Soviet regime in Azerbaijan in northern Iran. Iranian Government troops had gone into the province to supervise the election, meaning that the election would go the way the Government wanted. The pro-Soviet party would thus not control the Parliament.

The American Ambassador, George V. Allen, had apparently a significant hand in the outcome, which was desirable to the West. But no one should have illusions that it had resolved the problems of poverty amid feudalism. Arthur Millspaugh, foremost American expert on Iran, in a letter to Mr. Childs, had said as much.

Mr. Millspaugh, of the Brookings Institution, stated that thus far diplomatic influence in Tehran had been exerted to support the Shah and the Army so that the Government could take a firm hand in restoring the integrity of the country, that is, uniting the northern province with the rest, in opposition to Soviet domination. While on the right side, the U.S., he thought, was following a policy similar to the British and Russian imperialism of the early 20th century. "The present danger is that we shall jockey ourselves or let the Iranians jockey us into becoming a participant in the international rivalry which has plagued the country and kept it weak for 75 years."

He favored a cooperative agreement between Russia, the U.S. and Britain to enable Iran to exercise self-government, each renouncing any imperialistic interest in the country. Mr. Childs thinks it a sound approach to the problem.

In his recent book, Americans in Persia, Mr. Millspaugh had told of the Russians preparing the way for revolution, using every device during the war and since to divide Iran on the basis of class, identifying the U.S. and Britain with imperialism and exploitative capitalism.

Mr. Childs thinks the rejection by Russia of such a proposal would still leave it up to the United States to take a constructive step to aid the Iranians economically and technologically, to raise their standard of living. If not done, the Soviets would likely take control of the country to the exclusion of the British and Americans.

He thinks the Republican Congress therefore ought start formulating such a policy, with Senator Arthur Vandenburg leading the way. It was premature to crow over the recent concessions by the Soviets in Iran. Its problems had not yet been solved.

Samuel Grafton suggests the country as being controlled by Republicans, with nearly a Republican Administration now running it. President Truman had adopted the habit of anticipating what the Republicans would next do and then doing it first, for instance, ending all remaining price controls and housing controls.

If the Republicans adopted a plan to take a bath before the Lincoln Memorial every morning, the President would undoubtedly, he thinks, precede them.

The President was planning to propose his own amendments to the Wagner Act in anticipation of the Republicans passing their own to restrict union practices. The same was true of proposed budget cuts, to be put forward in the State of the Union message. In consequence, the Republican commentators were all now praising the President. Any complaint would apparently be met promptly by the President's new attention to service to the Republican Party. It was a position not taken in some time by a U. S. President.

It perhaps signaled that the bi-partisan bloc which had formed during the 79th Congress had now come to govern the nation. The Ickes types, Wallace types, and Willkie followers were now consigned to the hinterlands politically.

He adds that he did not mean to insinuate that Mr. Truman was a bad man. To the contrary, he considers him a "sweet man in a hurricane, which lifts him regardless of what he thinks."

A letter from the president of the Textile Workers Union of America comments on the December 13 editorial, "The Differential Is Still With Us", which had regarded the differential in wages between Northern and Southern textile workers. He suggests that the editorial had been premised on fallacious reasoning, that the comparison was between wages in the South before wage increase negotiations were completed and those of the North after such increases, that only a cent per hour separated wages before the Northern increases were implemented. He agrees that there was no justification for any differential.

The editors admit that they had not been fair in failing to take into account the announcement by TWUA that it intended to seek a 15-cent per hour wage increase for Southern textile workers. But, they add, until the union succeeded in achieving that increase, the differential nevertheless stood. And it would be no easy task to accomplish.

A letter writer suggests that the Winecoff Hotel fire had been the result of an organized gang operating in the country, led by a man whose name began with the letters "C. L."

This man reputedly owned a gold mine, producing 50 million dollars of gold a year, and he operated day and night all over the country. C. L. and his operatives were probably responsible for three-fourths of the hotel fires in the country, wrecks, and other deaths

A generation earlier, he had gone to jail for a number of years. Then his followers started a campaign utilizing the slogan, "Turn the Old Man Out", and it had worked. He was released in 1932.

His identity, the man finally reveals at the end of his missive: "

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()