![]()

The Charlotte News

Monday, August 13, 1945

FIVE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports that as of 10:45 a.m., White House press secretary Charles G. Ross stated that there had been no confirmation from Tokyo of acceptance of its own proposed terms of Friday, approved Saturday by the Big Four nations, with the added provision that the Emperor submit to control by an Allied military government, and transmitted to Japan at 4:05 Saturday afternoon, Washington time, albeit, according to Tokyo radio, not received until Sunday night at 9:04, 10:04 a.m. Monday, Tokyo time. Consequently, the war was continuing. As of 3:00 p.m., no change in status was reported. The terms had specified no time limit on Japan's decision.

Emperor Hirohito, according to a Japanese broadcast, spoke with Foreign Minister Togo at the Imperial Palace on Monday morning. Other broadcasts asserted that an invasion was nigh, based on the continued presence of American carriers and aircraft. Domei had not yet reported to the Japanese people the news of the tentative Japanese surrender of Friday and continued to insist upon their loyalty to the Emperor and to await his command.

A Japanese newspaper editorial indicated the Japanese outrage at the atomic bombs and that they were only solidifying the determination of the people to resist an invasion.

Would Fat Girl have to be dropped after all?

"I do not know," replied Mr. Ross. "If I did, I wouldn't say."

The report states its assumption of resumption of the attacks by atomic bombs should there be significant delay in the Japanese response.

There was no intention expressed of further communication by Washington to explain the meaning of any of the terms or conditions of surrender.

The State Department expressed disappointment that no reply had yet come.

Meanwhile, attacks from the Third Fleet continued, with some 550 planes hitting the Kanto District in the area of Tokyo for twelve hours, as well at nearby Yokohama.

Three million maps of Japan, for either occupation or invasion, were being printed by the Army engineers for distribution to the Army and Navy.

In Manchuria, the Russians, according to Japanese sources, had undertaken a major new offensive from Outer Mongolia across Inner Mongolia, aimed at the Yellow Sea, imperiling Linsi, western Manchuria road center and air base. Driving the remaining 240 miles to the Yellow Sea would cut the Japanese in China completely off from supply routes to Japan and separate off a half million of the 1.5 million Japanese troops estimated to be in China.

Soviet sources confirmed only that the Russian forces had advanced between nine and 22 miles toward Harbin, the central Manchurian arsenal. Russian Marines had invaded Korea, 90 miles south of Vladivostok, and seized the ports of Rashin and Yuki on the Sea of Japan. Throughout the war, these two ports had served as bases for shipping of armaments produced in Manchuria to the Japanese homeland. Tokyo radio stated that Russian troops had begun landing on the southern half of Sakhalin Island, Karafuto

It was reported from China that some detachments of Japanese troops had ceased firing in Chekiang province and had dispatched representatives to the Chinese lines to negotiate their surrender.

The Office of Price Administration had halted the printing of 187 million new ration books for food, shoes, and gasoline. The books had been scheduled for distribution in December. The order was tentatively stopped, pending final word of Japanese surrender. The stamps already in circulation were enough to last the population for rationing through the end of the year. When planned in July, it was thought that the books would be needed for most of 1946.

A false United Press report of peace had triggered premature victory celebration in some parts of the United States and Canada, Central America and Australia, before being halted at 9:40 p.m. Sunday night. The report had been flashed over some wires at 9:31. It remained a mystery as to the source of the report.

Colonel James Roosevelt had been transferred to inactive status by the Marine Corps, after combat fatigue had aggravated a stomach disorder, necessitating complete rest. He had been admitted to the naval hospital in San Francisco several weeks earlier and was now at his Beverly Hills home.

On the editorial page, "The Emperor" comments on the Japanese Constitution which had been issued by Prince Ito in the name of the Emperor in 1889, twenty years after the feudal lords had given up their property to the Emperor. That Constitution provided that the Emperor would rule Japan and was sacred and inviolable, not to be made a topic of derogation or discussion. The Constitution was represented as the Emperor's gift to his people. It could be amended only at the fiat of the Emperor.

The Government could do whatever it wanted to curtail the privileges of the people; religious freedom was allowed, subject to Government control at any time, meaning that the people had to believe in what they were told or else lose the freedom to believe what they were told and have it instead imposed upon them by the point of a sword.

The Emperor was subservient to the Army and Navy and the Genro, or elder statesmen, and the Privy Council. The Minister of War had to come from the Army, and the Navy Minister, from the Navy. No Government Cabinet could be formed without approval by the Army and Navy. The Genro ended in 1940 and the Privy Council since that time had selected the Premier. The Ministers of War and Navy had exclusive access to the Emperor, making him subject exclusively to their advice.

It quotes Baron Kiichiro Hiranuma, Minister of Home Affairs, as having asserted with pride in 1941 the uniqueness of Japanese Government, derived from "the heavenly-created throne" and not from mere mortals as other governments world-wide, which were temporal and thus likely to crumble.

Such beliefs still gripped the Japanese people, and the piece supposes that it was the primary reason that there was hesitancy to surrender, even in the face of all rational necessity begging it, to avoid complete and utter devastation of Japan and all of its inhabitants by the rain of weaponry which President Truman had promised otherwise.

A piece compiled by the editors appears on the page, as summarized below, picking up this history of the Emperor, with the dangerously mixed mythical and historic underpinnings of his power set forth.

"Sheep & Goat" contrasts the two Chicagoans, Mayor Ed Kelly, the preeminent Roosevelt supporter through his third and fourth term elections, and Robert McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, chief Roosevelt detractor and isolationist throughout the war.

Yet, recently, Mayor Kelly had appeared at a testimonial dinner for Col. McCormick at which he heaped lavish praise on the publisher. And, according to Drew Pearson, when Harold Ickes was about to lose his Chicago apartment house for nonpayment of taxes, Mayor Kelly had given the order that it be sold, to enable Mr. McCormick to crow after the Tribune would purchase it. Though the latter deal was never consummated, the Mayor's imprimatur on it had been bestowed.

It concludes that there was a strange relationship at work between the Mayor and Mr. McCormick.

"Double Standard" finds the new expense money voted by the House, $2,400 per year, plus higher salaries for House staff, to produce the paradox that the Senate, with greater prestige as a body, having failed to vote itself any raise, provided less pay to each Senator than the House now paid each Representative.

The House Parliamentarian, the Chaplain, the Clerk, the Postmaster, and other employees of the chamber received substantially more in salary than did their counterparts in the Senate.

As revenue bills started in the House, prospective politicians, it advises, might consider it a better choice for career.

"The Look" comments on the visit to Charlotte by John L. Lewis, present to observe the chemical textile industry, as well as other industries not identified. He stated that his appearance had been the result of inquiries received from textile workers seeking union organizers.

For unionizing outside the coal industry, Mr. Lewis used UMW District 50, a "up-and-at-'em outfit".

To have Mr. Lewis peering, or leering, at local industry gave rise, it suggests, especially within the textile industry itself, to "horrid thoughts". By contrast the TWUA of the CIO had high respectability and a touch of benevolence.

"Trouble, Trouble" wonders why the country had bothered to spend the billions of dollars and employ a half million workers it had to build an atomic bomb when, according to the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties, it had brought about such a quick end to the Pacific war that the country was about to be plunged into economic chaos and unemployment. The organization called for Washington immediately to legislate full employment, make permanent the Fair Employment Practices Committee, and pass other like measures.

The piece concludes: "We can't win. Why did we ever sweat over this horrible boomerang, anyhow?"

The excerpt from the Congressional Record has Representative Robert Rich of Pennsylvania reading into the record a letter from a constituent, a Jeffersonian Democrat, who wondered why Congress could not practice parsimony as recommended by Ben Franklin when he said, "I love economy exceedingly and willful waste makes woeful want."

Mr. Rich wondered why the Government retained numerous employees no longer needed for the war effort and expressed the hope that President Truman would pare down the waste. He believed in eliminating several agencies and consolidating others.

Quickly, name five.

Drew Pearson, writing from Gaithersburg, Md., states that he had taken a vacation the previous week, at the urging of his wife, and now had regretted doing so for the fact that the week had been freighted with such momentous events, the dropping of both atomic bombs and the entry to the Pacific war in the interim by the Russians with their two-pronged attack on Manchuria from east and west.

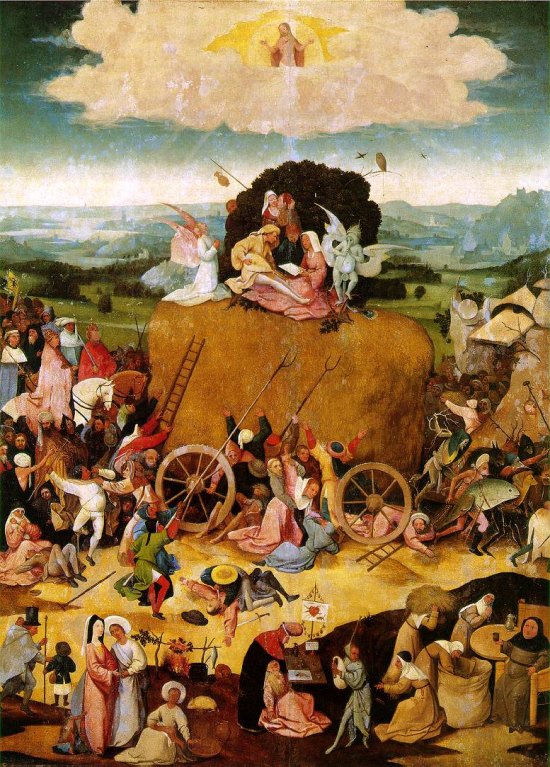

The while, Mr. Pearson confesses to have been wielding a pitchfork in his Maryland hayfield.

Since he was only fifteen miles from Washington, however, he was able to return to work intermittently during the week. But, he offers, being away from the center of the action had enabled him to gain better perspective on the events at hand.

He had been considering the history of war and that, in earlier wars, prior to the nineteenth century, not so many people were harmed by warfare. Knights jousted in armor while their women applauded. Wars were more localized and so dragged on often for many years without the people revolting.

The American Civil War was the first example of total warfare, as practiced by General Sherman, to destroy the capability of the South to support armies by waging war on the civilian population and the principal cities and railroads.

With the advent of modern weaponry, the airplane, the Norden bombsight, the rocket bomb, and now the atomic bomb, the civilian populations suffered increasingly and were suffering presently more than military personnel.

In modern warfare, the military commanders typically remained in bomb-proof shelters behind the lines while conscripts fought the war.

"So now, as of August 5, the day we dropped our first atomic bomb on Japan, we have reached the point in warfare which was absolutely inevitable, the point at which either we stop going to war or mankind reaches its own end."

Already, scientific planners, he assures, were working on such things as bases on the moon for the next war, from which rocket bombs could be launched against any nation. And, it seemed no longer ludicrous, but wholly achievable.

General William Donovan and his O.S.S. had been at work developing a worldwide spy organization for peacetime use to determine what other countries were doing.

Admiral Ernest King had drawn up plans for 73 warships not to be completed until three or four years after the war. James Byrnes had pulled the plug on those plans because they had been obviously aimed only at the Soviet Union.

The War Department had been urging peacetime conscription for the first time in the country's history.

In short, the military had been systematically planning for the next war, ignoring the plans for peace for which this war supposedly had been fought.

They had been moving forward apace with these plans as if the next war had been inevitable, until the dropping of the Hiroshima bomb a week earlier.

Notwithstanding, The New York News, the day after the Hiroshima bomb, editorialized that Canada should either voluntarily share its uranium deposits with the United States or have them forcibly taken away.

Peace, he suggests, was premised on good neighborly relations. The U.S. had led the way in setting a good example for the world in this area by the guardless borders between Canada and the United States and between Mexico and the United States.

In consequence, trade with Canada, Cuba, and Mexico was greater than with any other countries.

The only interruption of these positive relations had occurred in the distant past, with the landing of Marines in Nicaragua and Haiti. (He omits the Pershing punitive expedition in search of Pancho Villa into Mexico in 1916, following Villa's massacre of civilians in New Mexico, which was resented for the ensuing 17 years until the Good Neighbor Policy was inaugurated by President Roosevelt through Ambassador Josephus Daniels.) Otherwise, he posits, the U.S. had sought to maintain good neighborly relations in the hemisphere. It had not dammed the water from the Colorado River into Mexico but rather had formed a treaty under which the water was shared.

Despite these good relations, however, the country had kept out of war. He saw the problem of preventing future war to be much more deeply rooted than the United Nations was equipped to defuse. Though the U.N. was a start in the right direction, it had many limitations. He concludes that education, churches, and other such institutions had to bring about a fundamental understanding of basic Christian principles as set forth in the Sermon on the Mount.

"How we can do it, I don't know. But we must do it, or see civilization vanish from the earth."

Marquis Childs urges that credit be given to President Truman for an amazing job in his first four months as President, having taken the long view in his relations with Congress, and, rather than trying to force controversial reconversion legislation down their throats, sure to have caused embittered relations which might have delayed or even led to the defeat of ratification of the U. N. Charter and Bretton Woods, establishing the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to stabilize world currencies, he had stressed the latter matters and only soft-peddled the harder issue of reconversion. Mr. Childs sees the President's positioning in this manner to have been astute politically, paving the way for the Charter and Bretton Woods in short order.

The criticism, however, had come from many quarters that he should have done more with respect to reconversion prior to departure for Potsdam in early July. Now, Congress was in recess, scheduled not to return until October 8. Mr. Childs predicts that the President would soon call them back into session, itself likely to offend many members who needed the two-month recess following a period of momentous decisions.

But, to avoid a deep depression with a long recovery, with the end of the Pacific war, thought until a week earlier likely to last at least another six months to a year, now suddenly imminent within hours or days, the President would have to begin the process of putting forth a concrete reconversion program for emergency passage by the Congress. Prime among the points was the already proposed $25 per week unemployment compensation bill on which the Congress had thus far lagged.

White House pressure on this area had been absent for the prior month during the Potsdam Conference, but no one should fault President Truman, counsels Mr. Childs, for the omission, as he could scarcely accomplish both the critical agreements of Potsdam and put daily pressure on Congress before they adjourned. Ending the war in the Pacific and laying plans for occupation of Germany and resolving to the extent possible the issues with respect to Eastern Europe had taken precedence.

Harry Golden introduces a series of four pieces which he would offer on eight famous trials, as a prelude to understanding the historic place of the war crimes trials to come at Nuremberg.

He saw these eight trials of the past as a chronicle of society's effort to make the planet more inhabitable. In some of these trials, society itself had been brought before the bar of justice; in others, it was an ordinary murder case, elevated to high publicity.

The eight would be: Cataline's trial in the Roman Senate; Lt. Becker of the New York City Police Department, charged with the murder of gambler Herman Rosenthal in July, 1912, subsequently convicted and executed for the crime; the trial of Joan of Arc; the divorce suit of Henry VIII from Catherine of Aragon; the John Thomas Scopes "monkey trial", deliberately allowing himself to be charged in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925, as a test case on the state law making it a misdemeanor to teach evolution in the public schools; the trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus for treason; the trial of Leopold and Loeb for the thrill murder of young Bobby Franks in Chicago in 1924; and the case against Harry K. Thaw for the murder of Stanford White in New York in June, 1906.

To this list, after the Nuremberg trials, we could add:

1) The trial, conviction and execution in 1953 of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for allegedly passing information on the atomic bomb to the Soviets between 1945 and the first successful Russian test of an atomic bomb, August 29, 1949;

2) The Army McCarthy hearings of the spring of 1954;

3) The case against Dr. Sam Sheppard, tried and convicted for the murder of his wife in 1954, his conviction reversed through the representation of F. Lee Bailey and retried with Mr. Bailey as his attorney, found not guilty;

4) The investigation into the Kennedy assassination, though never resulting in any celebrated trial per se for the facts that Lee Oswald never got to trial and Jack Ruby's trial having not amounted to much as the defense conducted by Melvin Belli, known more as a torts attorney, was not guilty by reason of insanity, while the trial of Clay Shaw in New Orleans was treated by the press of the day largely as a sort of kooky witchhunt by District Attorney Jim Garrison;

5) The case of the June, 1964 murders of the three civil rights workers outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, stretching as it did over four decades, through June, 2004;

6) The Boston strangler case of 1962-1964, Albert DeSalvo also having been represented by Mr. Bailey;

7) The case against Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald, ultimately convicted in 1979 for the 1970 murder of his wife and two little girls, after being initially cleared by the Army inquiry at Fort Bragg in 1970, the 1978 Supreme Court case on the challenge for lack of speedy trial having probably set a miserably unfair precedent in American law and likely compromised justice in Dr. MacDonald's case, who was railroaded by a bunch of dishonest, power-hungry North Carolinians of the day, including the prosecutor, Mr. Blackburn;

8) The case against Sgt. William Calley for the My Lai massacre in Vietnam in 1968;

9) The Watergate case of June, 1972 and its several trials for various parts in the matter, and, more importantly to the public for the complete television coverage, the Ervin Select Committee hearings of the summer of 1973 and the House Judiciary Committee hearings on the Articles of Impeachment of July-August, 1974, which led to the resignation of President Nixon on August 8, 1974;

10) The trial of Patricia Hearst in San Francisco in 1976 for robbery of the Hibernia Bank branch the previous year, Ms. Hearst also having been represented by F. Lee Bailey;

11) The case against O.J. Simpson in 1995 for the alleged murder of his wife and Ron Goldman in June, 1994; and

12) The case of impeachment of President Clinton in 1998-99, albeit in the latter case far more a trumped-up media circus than any special trial, and, in any event, with obvious political motivations, short on any substance beyond the worst outbreak of yellow journalism in the history of the Republic—an increasingly outrageous display of which, in

pandemic fashion, has become nauseatingly the routine to sell cornflakes, embarrassing to all respectable journalism, not a throwback because there is no precedent for it so pervasively among the traditional organs of journalism, become instead infotainment, seeking appeal to the least educated brickheads of the population.

And, of course, as an extension of that concept, perhaps the granddaddy of them all, for both its importance at the time and its speed of decision, as farcically erroneous, repulsively political, and intellectually dishonest as it was, the case of Bush v. Gore, regarding the 2000 election results in Florida, on which hung the outcome electorally for that fateful election.

Well, we could go on, but we shall refrain. Those are the primary trials, as we observe them, occurring since 1945, if one assumes as criteria both public attention at the time and importance to society, quite apart, in most of those cases, from any lasting impact on the law of the land

One could add a myriad of Supreme Court cases which have had enormous impact on the law and society through time. To name but five of the principal cases since 1945: Brown v. Board of Education in 1954-55, establishing the necessity for desegregation of public schools "with all deliberate speed"; Baker v. Carr in 1962, establishing the concept of one-man, one-vote in striking down as unconstitutional the long employed concept of gerrymandering to accomplish favorable voting districts for a particular political party or agenda; Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963, establishing the right of indigents to have effective counsel at all critical stages of a criminal proceeding, including misdemeanor proceedings; the related case of Miranda v. Arizona, in 1966, establishing the right of an accused to be informed of his or her Constitutional right to have an attorney and of the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, before being interrogated regarding an offense for which suspicion has been focused on the suspect; and Roe v. Wade in 1973, still controversial, establishing the right of a pregnant woman, pursuant to the right of privacy, to choose whether to have an abortion through the first trimester of pregnancy.

We might add to Mr. Golden's list of famous trials prior to 1945, the case against nine black men for rape out of Scottsboro, Alabama in 1931 and the Lindbergh kidnapping case of 1932-35, plus the United States Supreme Court cases of Plessy v. Ferguson, Dred Scott, and the Amistad case of 1839-40, including its trial, among others going back to Marbury v. Madison.

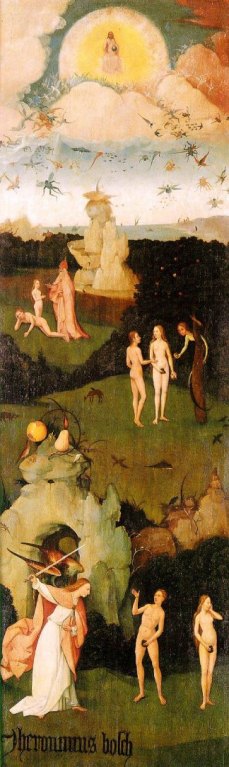

As indicated, a piece by the editors seeks to explain the role of the Emperor within the Empire of Japan during the course of the war. It asks rhetorically whether he was truly the keystone of the political, religious, and social order of Japan or whether that notion was simply myth.

It posits that his removal could lead to chaos which would prolong Allied occupation. His supposed divinity was taught in the Japanese schools and thus inculcated in the population from a young age.

The origins of his divine quality came from the notion that Izanagi, the father, and Izanami, the mother of the line of emperors, descended from Heaven to a small island which had clung to the end of Izanagi's spear, and when he dipped it into the primeval sea, the islands forming Japan were created. Izanami died giving birth to the god of fire, but from Izanagi had come the other gods and goddesses, including Amaterasu, the goddess of the Sun who ruled Heaven, springing from his left eye. She made the determination to populate Earth.

Eventually, she sent her grandson, Ninigi, accompanied by lesser gods, to Kyushu, where, in the year 660 B.C., the great-grandson of Ninigi became Emperor Jimmu, the first ruler of Japan, though essentially a tribal chieftain among the numerous competing clans.

Jimmu reported his assumption to the throne to Amaterasu.

By the seventh century, A.D., the power of the clans had slowly been concentrated within the imperial family. The Emperor was ruled by an oligarchic council of clan leaders, headed by the Fujiwara family, retaining power until the 12th century.

In 1167, the first of the Shogun military dictators was brought to power by the Emperor. The Emperor became isolated under Shogun rule and the seat of government was moved to Tokyo, away from the original Imperial Court. Oaths of loyalty were henceforth made to the Shogun.

During the 17th century, the Shogunate undertook measures to pacify the country, freeze the existing social order, and perpetuate the extant feudal system. No one could change occupation without consent of his lord. Swords were confiscated from the farmers. Class lines were drawn between the Samurai warriors and workers.

Eventually, wealthy merchants joined with the Samurai and some of the lesser feudal lords to re-establish allegiance to the Emperor and away from the Shogunate. The Shoguns themselves gave allegiance to the Emperor and so found it hard to resist this movement. In 1868, the last of the Shoguns was overthrown and the charter oath of Emperor Meiji, age 16, was issued, albeit setting up Meiji's power only through exercise by a Regency. The result was continued oligarchic rule, now exercised by the Genro or elder statesmen.

The country was unified by enhancing the prestige of the Emperor, and his Court was moved to Tokyo. Shinto was revived, with its emphasis on the Emperor's divinity and oneness with the Sun Goddess, his spiritual Mother.

Mass education was undertaken to permit indoctrination of the people with the old traditions of the Emperor as divine. Subservience to the state was inculcated as a duty of each individual. Feudal loyalties to individual lords were transferred to the Emperor.

Emperor Hirohito, descendant of Jimmu, was the 124th Emperor in the direct line, and, in fulfillment of the tradition, reported all of the affairs of State at the Shinto shrines to Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess—as represented during World War II on the aeroplanes by the Big Orange Circle.

At accession to the throne, the Emperor observed an all-night vigil during which the soul of Amaterasu entered his soul to make him the divine receptor of her wisdom.

It was this ridiculous child's story which had given birth to the notion of the Emperor's divinity, the foundations of Shinto, originally a type of pantheism indigenous to Japan.

Transposed to the United States, it would be as making King a supposed descendant of Adam and Eve, no doubt a snake in the grass.

This sort of notion abounding in the world of 1787, including Mother England and the Divine Right of Royalty, in an age in which illiteracy and lack of any formal education was more the common rule than not, is the primary reason that the Founders had the good sense to provide in the First Amendment Establishment Clause for the Separation of Church and State.

It had taken the American-sponsored collection of international scientists working at Los Alamos, with the teams at Hanford and Oak Ridge, to harness the power of the Sun to reduce finally to ashes this absurd myth of Hirohito being imbued with the power of the Sun.

Suddenly, the heat of old Sol had become a bit too much for the Sun King.

According to the British historian Frank Brinkley, who studied Japan during the latter third of the nineteenth century until his death in 1912, the bulk of Japan believed in the literal mythology, as strongly as Anglo-Saxon culture embraced the literal interpretation of the mythology of the Bible. The Japanese historian Yosuke Matsuoka—not to be confused with the Japanese Foreign Minister of the same name, responsible for the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy and the Russo-Japanese neutrality pact—had stated that the Emperor was the foundation for Japanese government, that, without him, there could be no Japan imagined.

Perhaps, as we suggested in 1998 at the start of this website, it was no accident that there is a myth in Oriental mythology, and specifically within Japanese mythology, that the pearl constitutes the "wish jewel", represented by "the pupil of a fish eye", or more refined in related Chinese mythology, the "moonlight pearl", as the eye of a whale—perhaps in some fashion related to the origins of Amaterasu out of the left eye of her father, Izanagi.

Jonah. Daniel.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()