![]()

The Charlotte News

Monday, April 16, 1945

THREE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page and inside page report that at 10:36 a.m. Sunday, the President's remains had been laid to rest at Hyde Park within the bounds of a century-old garden on the family estate on the Hudson, Krum Elbow.

The military band had played "Hail to the Chief" followed by

Chopin's all

Neighbors of the 32nd President, including a boyhood friend, were present, along with President Truman, James Byrnes, Cabinet officials, Supreme Court justices, Congressmen, military leaders and foreign dignitaries, including Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King and British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden.

Following a 27-gun salute by West Point cadets, the flag was folded and the casket lowered. The service

As reported on an inside page, Fala, tended by FDR cousin Margaret Suckley, at whose home he would temporarily reside, barked upon each of the three volleys of nine guns each. Said Ms. Suckley: "I wondered about it. It struck me in a way." She reported that Fala had been moping around, apparently depressed, for the previous three days since the passing of his Master. Once back home, however, his original home, and playing with the two pups he had fathered a couple of months earlier, she informed, he was returning to normalcy, "like he wanted to get out and hunt rabbits, just like any other dog."

As the earth was being replaced over the President's vault, Mrs. Roosevelt returned one last time to the garden, alone, to peer into the grave of her husband of 40 years.

She then caught the train back to Washington with the Trumans, to begin immediately the task of moving the family belongings from their residence of the previous twelve years.

She would live another 17 active years, becoming in 1946 a member of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations, continuing in that capacity through the end of the Truman Administration in 1952. She would also serve in the Kennedy Administration.

Mrs. Roosevelt, who reinvented the role of First Lady into that of an active and viable participant in political life, would pass away on November 7, 1962, the day after son James had won his fifth term from California to the House of Representatives, ten days following the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Many thought her an overbearing presence and disliked her liberal politics; as many admired her for her forthrightness and dignity, standing for what was right, regardless of political acceptability at the time.

Were it not for people in positions of power as the Roosevelts, we daresay, man would still be fighting for territory within the caves and crevices of places such as Okinawa or the Hartz Mountains.

President Truman, this date at 1:00 p.m., provided his first address to the Congress and to the people, insuring that he would follow the policies set in motion by President Roosevelt. The full text and audio of the speech are here.

While a Senator, the 33rd President had been a solid, though not unwavering, supporter of New Deal policies. The only variance expected was in the area of oversight of the military, for which he had, as Senator, during the previous three and a half years of his ten-year tenure, maintained while chair of the Senate Investigating Committee, stressing the supply and spending of the military, often coming to loggerheads with military leaders on the homefront for military waste. He had complained, for instance, that military officers serving in positions within civilian agencies should not wear the uniform of the military, reserved, he believed, for the fighting men.

A piece on an inside page states that close confidantes of the new President were speculating that Secretary of State Stettinius would be replaced following the United Nations Conference and that they would not be surprised to see former Justice and War Mobilizer James Byrnes appointed in his stead—which, of course, is precisely what would occur in late June. Secretary Stettinius would be appointed at that time as the first U.S. Ambassador to the U.N.

President Truman, not gifted as a public speaker, as was his predecessor, nevertheless had a plain folksiness which appealed to much of the country once it became accustomed to him. Some detested him with a passion, even exceeding that of the haters of FDR, thought him ill-suited to the presidency, a man without college background in the mid-Twentieth Century, sometimes in private substituting four-letter words for twelve-letter ones; others admired his tenacity of purpose and plain spokenness, not accepting any yap from anyone without response, whether the recipient of the Truman treatment was a critic of the singing voice of his daughter Margaret or the insubordinate hero of the Pacific war, General Douglas MacArthur. President Truman not only believed in freedom of speech but exercised it with the liberality of a farm-raised country boy who had fought in World War I at the front.

The new President and the prior President were in fact not very much different, save for a Harvard diploma and vast disparities in wealth on which they were raised. But as men, they were, at base, similar personalities, ebullient, confident, determined, believing in the same ideals, independent of mind and spirit, neither prisoners of their pasts or their party, both liberal.

But, whereas President Roosevelt had to get out among the people to know them, was "of them, but above them", President Truman was, to a great degree, one of them, certainly had come of age as one of them, as no one had who had achieved the presidency since U.S. Grant, Andrew Johnson, and Abraham Lincoln. He would amalgamate the best attributes of those three men with that of his mentor, President Roosevelt, and leave a fine record as President, the Fair Deal, the Marshall Plan, the MacArthur-led rebuilding of Japan, even if one which was not so admired by everyone when he left office in 1953, criticized heavily for his conduct of the Korean War, marked by McCarthyism, and widely disliked for his bold standoff with General MacArthur, leading to the relief of the latter from command in Korea.

The stature, historically, of the Man from Independence, however, would grow with time, especially the admiration for his honesty, as the country endured the excesses of Watergate and "that little Congressman from California" who had become President in 1969.

He had stated this date: "In the difficult days ahead, unquestionably we shall face problems of staggering proportions. However, with the faith of our fathers in our hearts, we fear no future."

He concluded with a verse from the Bible, Kings 3:9: "Give therefore thy servant an understanding heart to judge thy people, that I may discern between good and bad: for who is able to judge this thy so great a people?"

Bi-partisan praise of the speech and pledges of unity behind the new President were expressed uniformly by members of Congress.

On the Western Front, the 26th Division of the Third Army had advanced to within seven miles of the Czech border, after essentially bisecting Germany into northern and southern halves, besieging Chemnitz from a distance of 2.5 miles, south of captured Hof, 75 miles from the Russian lines. Frantically, the Nazis were transferring troops from the Eastern Front and from Berlin to try to halt the unremitting march of the Western forces, as the Ninth Army was positioned a mere 45 miles from the capital.

The Third Army alone had captured 5,869 prisoners on Sunday, 452,137 since D-Day. Total Allied prisoners captured on Sunday were 66,191, bringing the total for the first half of April to 814,286. The Panzer Lehr out of the Ruhr, one of the toughest of the remaining Nazi divisions, had been the prize. The Ruhr trap had now virtually been eliminated as the First Army took its 176,000th prisoner from the area, leaving only about 30,000 Germans still holding out. It had been the greatest single area of defeat for the Wehrmacht on German soil.

In addition to Hof, Wupperthal, Oberhausen, Hagen, Mulheim, Bayreuth, Bamberg, Stendal, Leuna, Walcrode, Bergen, and Ruhrort were also captured.

Three German divisions eliminated the original Ninth Army Elbe River bridgehead at Magdeburg, but the Barby bridgehead was extended five miles by elements of the 2nd and 83rd Divisions, moving to within 52 miles of Berlin along the open Brandenburg plain.

A German report stated that a new Ninth Army bridgehead had been effected 50 miles north of Magdeburg, at Havelberg, 45 miles northwest of the capital. The fighting in this area was the most intense since along the Roer River and in Cologne, in February and early March.

The First Army increased its hold on Leipzig while clearing the northern third of Halle, moving to within two miles of Dessau, 52 miles southwest of Berlin, moving close to joinder with elements of the Ninth Army. Both Armies now controlled 150 miles of the west bank of the Elbe.

The First and Ninth Armies together formed a trap of the Hartz Mountains, 350 square miles in area. So desperate had been the Nazis, reported General Eisenhower, that they had formed an army from remnants of the depleted ranks of the Wehrmacht, and, though in fact it had no SS members or tanks, dubbed it nevertheless the "11th SS Panzer Army", deploying it into battle in the area the previous week. This Army of ragtag soldiers with the impressive name had already been vanquished.

A complete ring, with a radius varying between 25 and 50 miles, was now surrounding the smoldering remnants of Berlin. Yet, the Fuehrer still cowered in his Bunker, with his equally cowardly pal, Herr Doktor Goebbels.

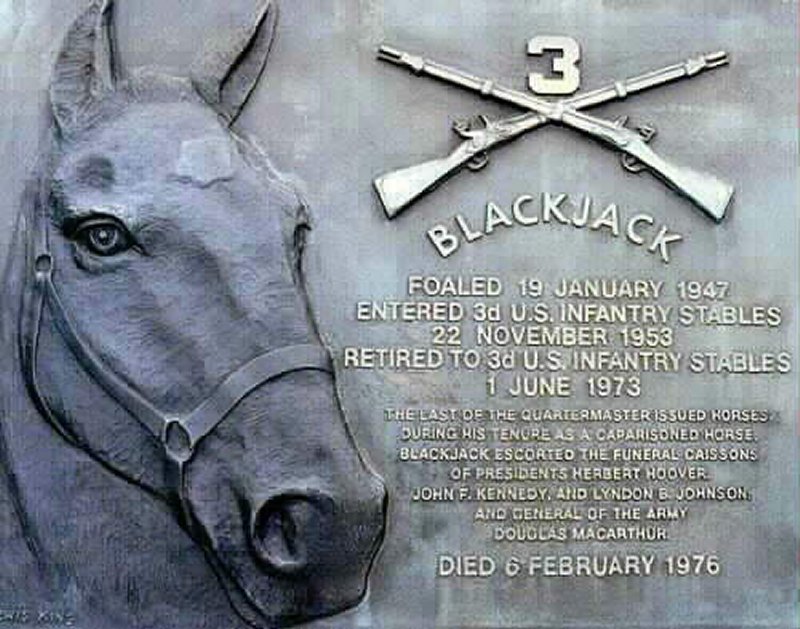

They had but a fortnight's worth of mornings remaining. There would be no State funerals, no caissons drawn by six white horses and a Riderless Horse, no ceremonial burials with 27-gun salutes, only the well-deserved ignominy of the same smoldering ashes, following a gasoline-doused fire, to which they had reduced their once proud country, to ruin and Ragnarok.

The artist turned dictator was about to receive his final rites.

Field Marshal Ernst Busch, pulled from mothballs after his defeat on the Eastern Front several months earlier, was now in charge of the northern front guarding Berlin. It was believed that Field Marshal Albert Kesselring was in charge of the southern front.

The German Western Front, however, no longer properly existed, save in the mind of Adolf Hitler. Kesselring would be one of the few German commanders to survive into old age, dying in 1960. Busch would die in a British prisoner-of-war camp in mid-July, 1945, probably of supernatural causes.

Hitler this date exhorted the defense of Berlin against the final Russian assault, to exact a bloodbath, warning that the "Jewish-Bolshevist" soldiers would kill old German men and rape women and girls alike, with the remainder taken to Siberia.

The Seventh Army pushed five divisions against Nuernberg, birthplace of the Nazi Party, moving to within eight miles of its outskirts, 160 miles from Berchtesgaden and 97 miles from Munich.

The British began shelling Bremen, just 2.5 miles distant. Canadians and Poles reached the North Sea, within five miles of Emden, trapping as many as 200,000 German soldiers. The Dutch cities of Lecuwarden, Zwelle, Menpel, Herrenveen, and Winschoten were captured. Some 6,500 American and British prisoners-of-war had been liberated in the action.

More than 3,500 Allied planes attacked Germany, from Berlin to Regensburg, striking at least fifteen railyards and bridges along German supply routes. Some 750 American heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force hit the Regensburg area targets and airfields near Berchtesgaden. Another 850 medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force struck targets in central Germany and Czechoslovakia. Berlin was struck three times during the night. During the morning, another force of 450 American heavy bombers struck German coastal gun emplacements on the Gironde estuary at Bordeaux for the third consecutive day.

On the Eastern Front, German sources stated that the final Russian assault on Berlin had begun at 3:00 a.m. along a hundred-mile front, breaking through German defenses and moving to within 25 miles of the capital, starting from the mouth of the Niesse River southeast of Berlin, capturing Seelow Heights, 27 miles to the east of the capital and 11 miles west of Kuestrin, linking up bridgeheads across the Oder southwest and northwest of Kuestrin. A new bridgehead across the Oder at Schwedt, 30 miles south of Stettin and 108 miles from American lines on the Elbe, was reported established. Other Russian forces were only 71 miles from American lines, at Wriezin, 24 miles northeast of Berlin. To the southeast, other Russian units struck at Furstenberg on the Oder, moving toward Beeskow, 27 miles from the capital and 87 miles from American lines at Dessau.

General Mark Clark announced that the spring offensive had begun in Northern Italy, with the British Eighth Army and the American Fifth Army engaged along the entire battlefront south of Bologna, gateway to the Po Valley. The attack of the Fifth Army had been preceded by a bombing raid of 1,233 heavy bombers of the Fifteenth Air Force, striking German positions south of Bologna, at places within 5.5 miles of Fifth Army lines. British Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander assured that, while the Germans were tottering and weakened, the fight would not be a "walkover", and that the "mortally wounded beast still will be very dangerous".

Another large B-29 raid hit Tokyo, this one the largest yet, consisting of 400 Superfortresses, following on the heels of a large Saturday raid which had destroyed nearly 300 million square feet of the capital. An estimated total of 27.5 square miles of the city had now been destroyed with incendiary bombs. Also hit on this date was Kawasaki, suburb of Tokyo.

On Okinawa, the Japanese line on the southern part of the island noticeably slackened its artillery fire against the Tenth Army, which, together with the Marines, were in control of the northern two-thirds of the island. Marines in the north were within ten miles of the northern tip in mopping-up operations, expected to continue for several weeks against the dug-in caves and crevices in which the Japanese were holed up.

More than a hundred spear-carrying Japanese troops had undertaken a banzai-style raid on American positions of the 184th Regiment of the 7th Division Saturday night. Half of them were killed and no American casualties were inflicted.

The Americans invaded Keufu in the Kerama Islands just off the southwest coast of Okinawa, as well as seven other islands of the group, all taken against light resistance.

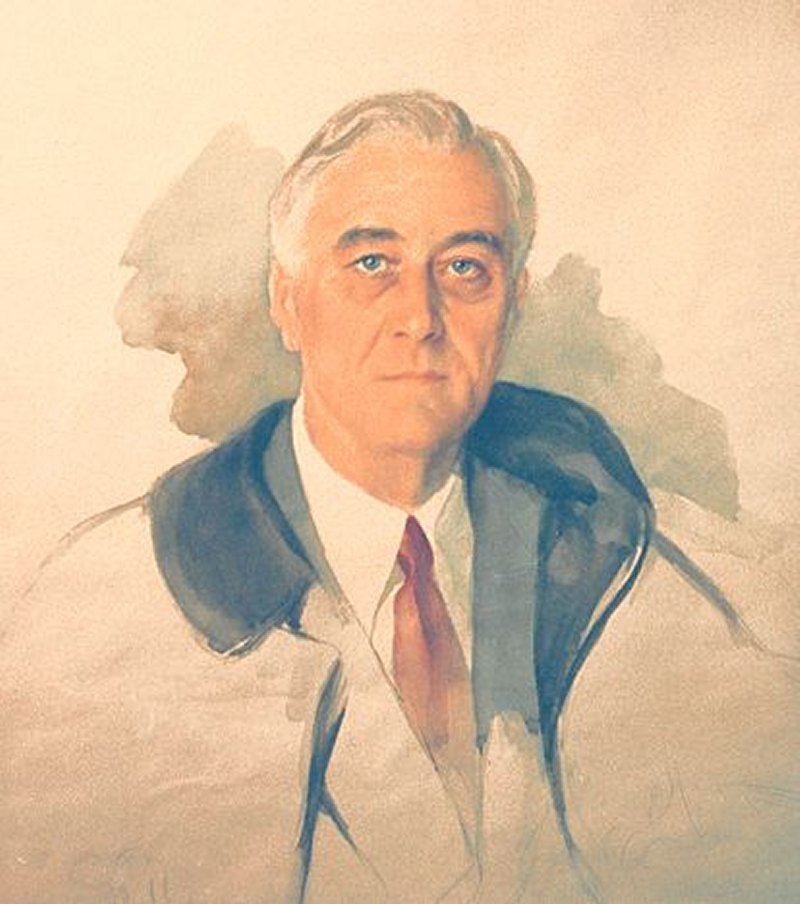

While we had thought to place a special note on Sunday regarding material surfacing after President Roosevelt's death anent his health status during the last months of his life, we discovered on the inside page of this date a piece on the artist, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, who had been sketching the President's portrait at the time of his stroke, and so decided instead to place that material here.

The piece tells of Ms. Shoumatoff's version of the scene. The President had looked fine when he had greeted her that morning. As she painted him, with cousins Laura Delano and Margaret Suckley and presidential secretary William Hassett present in the room, President Roosevelt had moved out of pose, shifting his head to one side, apparently engrossed in paperwork he was reviewing before lunch. Then, as she was determining the colors to be used in the final version of the portrait, she noticed that he placed his left hand to his temple—the side from which, it was reported Friday, he had apparently been suffering impaired hearing, as evidenced at recent press conferences. He then put his hand to his forehead, lay back, reclining into the chair, losing consciousness. Ms. Delano and Ms. Suckley then rushed over to him, just as the butler was entering the room.

She made no mention of the statement attributed to him by Ms. Suckley, that he had a "terrific headache" or that he placed his hand to the rear of his head.

After asking one of the Secret Service men to summon a doctor, Ms. Shoumatoff left the Little White House, without knowing the President's condition. She called from Macon and was informed that he had died.

She intended to complete the portrait and hoped that it might hang at Hyde Park in the library of the President.

Ms. Shoumatoff, being Russian-born, having immigrated to the United States during the Teens, subsequently became the object of suspicion by some, that she might have been a part of some international plot to assassinate the President. Also, rumors developed within about a month that the President had been suffering from prostate cancer, having been diagnosed in October, supposedly told by doctors on Friday the 13th of October that he had but six months to live, then, the story continued, looking to the calendar, seeing that the end coincided with Friday the 13th of April, giving a laugh.

We present this material because it circulated at the time, though not being given any credit by reliable historians then or since. Aside from its dubious format, presented in a tabloid type publication, it is nevertheless intriguing, if questionable in the considerable leeway of surmise and inference it derives from otherwise undisputed factual material, adding in the unconfirmed reports of prostate cancer.

That there was either that resultant expectancy or foul play involved in the President's death, while intriguing, begs, just as with the supposed affair with Lucy Mercer and her supposed presence on the scene at his death, any credulity.

Mr. Roosevelt, after all, had been confined to a wheelchair for 24 years, since August, 1921. He smoked two packs of Camels daily, had, by a report in December, vowed to cut his habit slowly to a mere one pack a day—still enough to choke a horse. Thus, that he might have in fact suffered from cancer is certainly not beyond the pale of suspicion. Yet, there is no solid medical documentation which attests to it, nor any documentation that he knew of his impending death.

Then again, the Drew Pearson column this date lends considerable credence to the notion that it was not unknown on Capitol Hill that the President was in a bad way in his health, Mr. Pearson reporting that House Speaker Sam Rayburn had specifically called Vice-President Truman to meet with him on Thursday afternoon to discuss the President's health, to urge him to prepare for the inevitable, that Speaker Rayburn believed and had informed dinner companions just on Wednesday night that the President had not long to live.

Even had FDR known that he would soon die, it does not smack of some sinister cover-up. Assuming the veracity of the report, how, pray tell, could the President have pulled out of the race in October, 1944, or revealed his condition to the public, at such a critical time in the war? Indeed, had he known of it even before being nominated, how could he have done so without risking the peace, without placing undue obstacles in the path of international agreement on the United Nations Organization, especially with respect to the Soviets, on the fear that the successor, the young, untried Thomas Dewey, who had already stated his intent to allow the generals to determine the course of the war, might not abide the same policies enunciated by Mr. Roosevelt? It is not just a political argument but one with ultimate practical concern behind it. We presume in this analysis the winner, without Roosevelt as the opponent, to have been Governor Dewey, against a hopelessly divided Democratic Party, North and South, left to nominate Senator Harry F. Byrd or Vice-President Wallace or former Senator and Justice James Byrnes or Senator Alben Barkley, Byrnes likely being the only viable candidate who might have won, but very much opposed by organized labor, the reason he was not nominated even as vice-president. Regardless of whether Thomas Dewey would have won or, if so, would have continued the policies of the war in just the same manner, the ability of President Roosevelt to accomplish much in the last months in office would have obviously been trimmed, risking a repeat of the dooming of the League of Nations, as with the transfer of power from President Wilson to President Harding in 1921 which had led directly to the vote against U.S. membership. Thus, the dilemma at such a crucial stage of the war, both in Europe after D-Day and in the Pacific following the taking of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Marianas, and the initiation of the B-29 raids on Japan, was real and undeniable.

As a rather bizarre sidelight, F.B.I. Special Agent Guy Banister would send a letter to Director J. Edgar Hoover, dated June 2, stating that the rumors of the President's prostate cancer had come to light out of New York, and that other rumors had it that "the reason so much trouble is being encountered with the Russians at the present time" was that the President's condition had been so far advanced at Yalta that his mental acuity had been adversely affected, to the degree that he made so many commitments that neither President Truman nor anyone else understood their extent.

Mr. Banister, who was then acting as head of the Butte, Montana, field office, and was also in charge of the Chicago office, related the information without comment as to his own opinion of it.

It is noteworthy for its having been brought to the attention of the Director, and because Mr. Banister has been linked, following his retirement from the FBI, to anti-Castro Cuban gun-running activities out of his Lafayette Street office in New Orleans in 1963.

Lee Oswald, when arrested for engaging in an apparent imbroglio with anti-Castro Cubans on Canal Street in August, 1963, had listed, on the "Fair Play for Cuba Committee" pamphlets which he had been distributing, a Camp Street address, just around the corner from Mr. Banister's office, and within the same building, even if in different parts of that building, supposedly not interconnected, their physical interconnection or not being beside the point.

As we have mentioned previously, all of this activity fit well into the planned Operation Northwoods program which former Joint Chiefs Chairman General Lyman L. Lemnitzer had recommended to President Kennedy in March, 1962, seven months before President Kennedy obtained his resignation and moved him ultimately to the position of Supreme Allied Commander of NATO, just prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis, replacing him with General Maxwell Taylor, head of the 101st Airborne Division during the Battle of the Bulge.

President Kennedy had denied permission for Operation Northwoods to proceed, a program comprised of a rather crazy-quilt set of feints and winks, including the contingency plan to shoot down a drone aircraft full of supposed American college students and claim it to be the act of Cuba, including the use of college students and young people to act as dissidents in support of Castro's Cuba, creating public disturbances in that role within the American South with the intent of disaffecting public opinion from Castro, while in fact being directed by the CIA. All of the activity was designed to stimulate excuse for an American invasion of Cuba, the creation of "Remember the Maine"-type incidents.

Make of it all what you will, remembering that Mr. Banister only quotes rumors in his letter to Mr. Hoover regarding President Roosevelt's health prior to his death, not alleging them to be based on any factual material, but rumors which fit his later evident anti-Soviet obsession, to the point of breaking the law in 1963 with respect to gun-running to the Cuban refugees bent on overthrowing Fidel Castro—an act which could have in 1963 compromised the carefully worked out agreement of October, 1962 to end the Cuban Missile Crisis, based in part on the assurance that the United States would not in the future invade Cuba, and led then to such destabilization of U.S.-Soviet relations as to result in nuclear war, especially after the displacement in October, 1964 of Nikita Khruschev with Alexsei Kosygin and Leonid Brezhnev, serving for a time in the dual capacities in which Khruschev had served, that of Premier and Secretary of the Communist Party, respectively, both Kosygin and Brezhnev being perceived as more dedicated Communists by that point than Khruschev, who had been backed down by the West in 1962, causing, in the apparent view of many hard-lined Communists, Russia to lose face.

Bear in mind, too, if you should happen to be under about age forty, that 18 years seems not that long after one reaches a certain age at which eighteen years in the past does not represent youth. Mr. Banister was 63 in November, 1963, 64 at his death on June 6 the following year.

On the editorial page, "The Man Who Is President" starts with the simple plea which President Truman had spoken to the American people, "Pray for me!" It finds in the simple words revelation of the inner man and forecasts that it would take some time for the American people yet to come to know the new occupant of the White House beyond the reports of his rise from poverty as a farm youth, his having been tapped by Boss Tom Pendergast of Kansas City in 1934 to run for the Senate from a county-level position, his having won re-election in 1940 while Pendergast was in prison, his nearly unwavering support of the New Deal while not giving blind obeisance to Administration-favored policies.

Among his nay votes in the Senate had been suspending poll taxes for soldiers voting in Federal elections, the FDR-favored $25,000 salary limit, the termination of the National Youth Administration and the Farm Security Administration, and the anti-strike bill for the duration of the war. He had supported the Administration in his votes against the bill to leave to the states the manner of absentee soldier voting and in his oppposition to the anti-subsidy bill designed to end or curtail farm subsidies, as well as voting for most Administration-backed legislation.

The piece finds in the new President a streak of independent thought, not cut strictly along party lines. It found his self-description, "just to the left of center", to be accurate.

"Memorial" compliments the resolution adopted by the 38 Republican members of the Senate, signed by Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, pledging their full support to President Truman in both winning the war and establishing a successful peace.

The piece suggests that such magnanimity would stand as a monument to the greatness of President Roosevelt, the perpetuation of his ideals in public men and private.

"No Change" finds it not surprising that South Carolina was adhering to its long tradition of suspicion of voters and their balloting, evidenced by the practice of making each voter declare his party choice by having to choose one ballot or the other when entering the voting booth. If a Democrat happened to intend to vote Republican, the news would be broadcast far and wide, stigmatizing the renegade. There were only 1,727 Republicans registered in the state.

Pursuant to complaint, especially by minority groups, the State House had decided not to investigate the system, determining by inaction that it needed no overhaul.

The excerpt from the Congressional Record has Senator Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin remarking on the secret agreement at Yalta regarding the disproportionate voting to be accorded the British Empire, with six votes, the Russians, with three votes, and the Americans, with three—the latter commitment subsequently indicated by President Roosevelt to have been relinquished without bothering the other agreements.

He finds in the agreement no danger, as unity was not a matter of counting heads but rather the spirit to be invested among the nations. The mechanism for reaching agreement, he offered, was not so important, but whether there could be a meeting of the minds between such disparate interests across the globe, heretofore never effectuated. That which was important was to achieve the lasting peace.

Samuel Grafton discusses the world food situation, that the French and Dutch and British could scarcely understand why Americans, able to consume 3,600 calories per day on average, were heard to complain about food shortage. He further remarks that the level of resentment was exacerbated in Europe by the fact that the German prisoners-of-war were fed so well by the Americans, fed better than the average liberated French or Dutch civilian.

The rationale for feeding the prisoners so well was to prevent maltreatment of American prisoners. Yet, the liberated Americans had endured starvation, subsisting on soup and a loaf of bread split between five men for two days at a time.

Marquis Childs discusses Assistant Secretary of State Will Clayton, the wealthy cotton broker from Texas, having undermined admirably his reputation as a man favoring big business over the small company by testifying before the Senate in favor of competition among the airlines for international routes, disfavoring the plan of having only one such international airline representing the United States. Pan American was foremost in the field and such a position would have inevitably favored it to the exclusion of other American airlines interested in the international routes.

British Overseas Airways Corporation, not yet flying to Miami Beach, had the British monopoly on international routes, and so it would be convenient to have one American company in competition. But the result would be higher fares and thus fewer customers. Mr. Clayton therefore found monopoly to be no salvation or replacement for American ingenuity and competition.

He had likewise proposed competition in the field of international communication, despite the Navy having favored occupation by only two or three companies to conserve frequencies on the radio band.

Mr. Childs had been impressed by his firsthand viewing of the testimony of Mr. Clayton. The expressed view, he opines, got close to what the war had been about in large part, the elimination of international cartels, which had prepared the way for war, restraining trade and thus preventing economic expansion on a broad scale, spread among nations.

Drew Pearson discusses Harry Truman as the man who did not wish to become President. He had enjoyed his job as Senator.

Once, during the campaign, he had dreamed that President Roosevelt had died and he was suddenly made President. He had awakened in a cold sweat. When on Thursday he had gone to the office of Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, he was going there to discuss the possibility of that happening, when he got the call to come immediately to the White House, where Mrs. Roosevelt informed him that the

On Wednesday night, Speaker Rayburn had informed friends over dinner that he believed the country was in for a great tragedy soon, that he believed the President would not live much longer. He had stated that the President was "not a well man". He said then that he would need to talk to Vice-President Truman the next day, to make him ready to carry the burden when called upon. It was at 3:00 that Speaker Rayburn called the Vice-President and invited him to his office. Mr. Truman had indicated that he would be over as soon as the Senate recessed.

Right after his arrival at Mr. Rayburn's office, as if on cue, the call came from Steve Early, still, however, not informing Mr. Truman what had happened.

Mr. Pearson next tells that, during the Democratic Convention the previous July in Chicago, Senator Truman had received a call at the Blackstone Hotel, indicating that "Mr. Hopkins" was on the line. The Senator immediately thought that it was the hotel man from Kansas City, had no idea that the caller referred to Harry Hopkins, the President's long-time adviser. Mr. Hopkins then informed the Senator that the President wished him to join the ticket as his running mate. Mr. Truman replied that he did not want the job, believed that the invitation was not tendered seriously, would await word from the President, himself.

Late that night, with the convention nearly deadlocked on the question of who would be the vice-presidential nominee, the incumbent Henry Wallace, Mr. Truman, or Alben Barkley, the President called and assured him that he was his pick.

Nervous, he went to see a movie.

When the balloting was complete the next day, the Missouri Senator sat eating a hot dog and drinking a soft drink behind the rostrum as his name was called as the nominee of his party—not once but several times, as Mr. Truman remained oblivious to the fact. Finally, it was brought to his attention and he stepped to the podium.

Mr. Pearson recounts Senator Truman's strong stands while chairing the Senate Investigating Committee, standing up to the military brass hats without fear, standing up to the Administration without partisanship when matters of military overspending and waste came to light. He earned bi-partisan respect on the committee in that role. He had taken to task General Breton Somervell when it had come to light that the Army had constructed a pipeline to carry oil uneconomically across Alaska. He had informed of the inefficiency of Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones in not properly planning for synthetic rubber plants to replace the rubber lost in Malaysia and the Dutch East Indies to the Japanese in 1942. He had exposed the Alcoa Shipshaw Plant in Canada and its failure to produce as expected in the war effort despite the huge Jesse Jones-approved loan from the Government, criticized the Navy for delay in accepting the Higgins boat, delaying D-Day. He had likewise criticized the Army for its waste of food, storing tons domestically in rotting conditions in warehouses, took to task the dollar-a-day corporate men serving their own corporate interests while sitting on the War Production Board, and had revealed delays in steel and aluminum production.

Mr. Truman, he assures, was a team player nevertheless and would conduct the Executive Branch in that manner.

![]()

![]()

![]()

One more thing must be referred to—the prevalence of superstitious beliefs concerning the Titanic. I suppose no ship ever left port with so much miserable nonsense showered on her. In the first place, there is no doubt many people refused to sail on her because it was her maiden voyage, and this apparently is a common superstition: even the clerk of the White Star Office where I purchased my ticket admitted it was a reason that prevented people from sailing. A number of people have written to the press to say they had thought of sailing on her, or had decided to sail on her, but because of "omens" cancelled the passage. Many referred to the sister ship, the Olympic, pointed to the "ill luck" that they say has dogged her—her collision with the Hawke, and a second mishap necessitating repairs and a wait in harbour, where passengers deserted her; they prophesied even greater disaster for the Titanic, saying they would not dream of travelling on the boat. Even some aboard were very nervous, in an undefined way. One lady said she had never wished to take this boat, but her friends had insisted and bought her ticket and she had not had a happy moment since. A friend told me of the voyage of the Olympic from Southampton after the wait in harbour, and said there was a sense of gloom pervading the whole ship: the stewards and stewardesses even going so far as to say it was a "death-ship." This crew, by the way, was largely transferred to the Titanic.

The incident with the New York at Southampton, the appearance of the stoker at Queenstown in the funnel, combine with all this to make a mass of nonsense in which apparently sensible people believe, or which at any rate they discuss. Correspondence is published with an official of the White Star Line from some one imploring them not to name the new ship "Gigantic," because it seems like "tempting fate" when the Titanic has been sunk. It would seem almost as if we were back in the Middle Ages when witches were burned because they kept black cats. There seems no more reason why a black stoker should be an ill omen for the Titanic than a black cat should be for an old woman.

The only reason for referring to these foolish details is that a surprisingly large number of people think there may be "something in it." The effect is this: that if a ship's company and a number of passengers get imbued with that undefined dread of the unknown—the relics no doubt of the savage's fear of what he does not understand—it has an unpleasant effect on the harmonious working of the ship: the officers and crew feel the depressing influence, and it may even spread so far as to prevent them being as alert and keen as they otherwise would; may even result in some duty not being as well done as usual. Just as the unconscious demand for speed and haste to get across the Atlantic may have tempted captains to take a risk they might otherwise not have done, so these gloomy forebodings may have more effect sometimes than we imagine. Only a little thing is required sometimes to weigh down the balance for and against a certain course of action.

—from The Loss of the S.S. Titanic: Its Story and Lessons, by Lawrence Beesley, surviving passenger, 1912

![]()

![]()

![]()