![]()

The Charlotte News

Tuesday, February 15, 1944

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

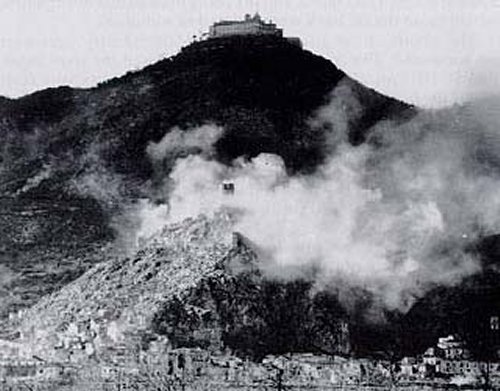

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports that four waves, each consisting of between 30 and 36 Flying Fortresses, beginning at 9:30 a.m., bombed the peak of Mt. Cassino whereon the Benedictine Monastery was located, some of the bombs striking the monastery itself. Around three hundred German soldiers fled the abbey into Allied artillery fire as the bombs hit, about fifty having fled during the first wave, and another 200 or so upon the second wave.

Fliers warning of the impending raid had been delivered the previous day to the monks of the abbey, founded in 529 A.D. It was not yet known whether they and the 2,000 civilians within its walls, refugees from the town of Cassino below, had heeded the warning and left.

The caveat had explained that the time had of necessity come when the Allies must bomb the monastery for its becoming a fortified haven for the Nazis from which to direct fire down on Allied positions. Numerous Allied infantry troops had already been killed during the previous fortnight trying to crawl up the hill toward the abbey in the face of German fire either from within its walls or directed from observation posts within.

The summit of Monte Cassino was strategically vital to either side for its overlook of the Via Casilina to Rome, seventy miles to the northwest.

Thus began that which historically has become known as the Second Battle of Cassino, the first having lasted from the Allied offensive begun January 12 to February 9. This battle would last only four days until the beginning of the Third battle, lasting from February 19 through March 23. The Fourth and final battle would begin May 11 and conclude June 5.

As the photographs below show--first in the the pre-bombing view of the abbey, then as the bombs were dropped on this date, inflicting much of the damage done to the structure, and finally on May 18 when the summit was occupied by the Allies--the monastery was decimated. Though it took twenty years to restore, being re-consecrated by Pope Paul VI in 1964, the monastery was completely rebuilt and appears today as it was before the bombing.

There apparently exists a mistaken view of some "historians", most probably having its derivation from disinformation promoted by Nazi propaganda during the war, not properly filtered out of certain "histories", (written by persons with the functional equivalent, if not the fact, of an eighth-grade education), that the abbey was not being used by the Nazis at the time of the bombing, only serving as a refuge for civilians, and that it was only used as a German fortress after the bombing, after it had been laid to ruin.

That is simply false, an absurdity when considered at any length. It takes but a little imagination to understand that the Allies were not without binoculars and eyes through which to view the abbey from the hillside and below, not to mention air reconnaissance. It is nonsensical thus to believe that the Allies could not see from whence emanated machinegun fire and artillery shells raining down on them from above during a period of fully two weeks before this date. If the abbey housed only observers to direct artillery fire by coordinates, then the precision of those coordinates also had to derive from somewhere in the vicinity, with sufficient vantage to observe the precise positions of the Allied soldiers. That was the abbey.

But, some "historians", seeking "balance" and "fairness", will give credit to Nazi propaganda, whether deliberately ignoring the facts consonant with logic or just being plain stupid, residing in the occlusion most characteristic of obscurantism which these "historians" practice, or perhaps in the incessant, wasted haste without due contemplation which most characterizes the product resultant of that all too often supervening edict within some "university" environs, "publish or perish". You will know them by their nonsense, when considered.

Meanwhile, as the rain and cloud cover had now cleared, Allied bombing of Northern Italy continued, in an effort to relieve the Anzio beachhead where fighting persisted, as during the weekend, in a see-saw fashion.

Bombing resumed on Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific, important airfield supplying enemy positions in the Marshall Islands. The airfield had been hit repeatedly between January 30 and February 5.

It was during a raid on Engebi airfield within this atoll on February 2 that the Avenger bearing Raymond Clapper crashed into another American plane, killing all aboard both planes.

Meanwhile, the Japanese struck on Friday at Roi airbase, recently captured by the Marines on the northern tip of Kwajalein in the Marshalls. Admiral Chester Nimitz indicated only moderate damage from the raid.

American troops occupied without opposition Rooke Island, to take control of both sides of the Vitiaz Strait, located between New Guinea and New Britain, providing an avenue into the Bismarck Sea to the Caroline Islands.

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox reported that a blockade had been imposed by Allied warships on the Bay of Biscay, to prevent German blockade runners from bringing vital war materials from Japan’s Southwest Pacific holdings into Spain and thence to France or Germany for manufacture. A great amount of material, said the Secretary, had been coming to the Reich's factories via that route. Based on the sinking of three German blockade runners reported February 4, the shipments primarily consisted of tin, ores, and rubber, and very probably some oil.

The Secretary also reported that American bombers were now operating at will in the Marshalls and extending west as far as the vital Japanese supply dump at Truk. The Japanese were said to be starving at this point in the remaining Marshall Islands not yet taken, having been severed from their supply routes.

He added, too, for levity, that the Japanese had proclaimed that 1,065 Allied planes had been shot down over Rabaul; in fact, only 30 to 40 planes had been lost in that area.

More American bombing raids hit Rabual on New Britain, Kavieng on New Ireland, and Wewak in New Guinea.

The Marines on Cape Gloucester gained another three miles, to a village near Cape Mensing, twenty-one miles from the point of landing December 26.

In Russia, the Red Army stopped a wedge of tanks forming a counter-offensive northwest of Zvnigorodka in the upper Dnieper Bend, seeking to rescue the trapped ten divisions of German troops west of Cherkasy, centered around now-captured Korsun. German Field Marshal Fritz von Mannstein was said to be apparently oblivious to the huge numbers of men and tanks being lost by his forces in the futile rescue effort.

An unconfirmed report indicated that unofficial communications from within the Soviet Government had been relayed to the Finnish Government in Helsinki to the effect that the Soviet Union would not demand any significant territory of Finland, provided it would unconditionally surrender and enable access by Russia to all its sea, air, and communications facilities. Another report indicated the belief that, in terms of territory, the Russians were demanding only that the borders established in March, 1940 at the conclusion of the Russo-Finnish war continue to be recognized.

Hal Boyle reports of the sad state of civilian casualties for whom care was being provided in the field hospital on the Cassino front, a whole family practically wiped out in one case, leaving a six-year old boy, Leonardo, with a gash in his head suffered December 27, probably eventually to die, seepage from the badly infected wound giving an odor all the way across the room. He belonged in the hospital at Venafro, said a medic tending him, but that facility was full and no longer receiving wounded.

A press report from a Nazi-controlled organ in Stockholm promoted the fact that German veterans of the war in Russia were now fighting on the Cassino front against Texans, who were likened to the Russian fighters at Stalingrad.

Given the result at Stalingrad in early 1943, it is questionable how that remark would have provided boost to German morale at home. Perhaps, it was subliminally to equate the Texans with those manning the mission amid the cottonwoods called the Alamo, given that the Germans had been holed up in the Benedictine Monastery on Monte Cassino. But then, wouldn't that mean…?

And Rome radio reported that Allied planes bombed Rome, dived down to machine-gun civilians. We assume that, somehow, the Pope was able to escape, despite his obviously having been targeted. Indeed, it is likely that Bruno Mussolini, notwithstanding his reported death earlier in the war, was now flying with the Allies, having formed the special "Blooming Red Rose" unit.

On the editorial page, "Dreaming" assesses the delay in bombing Monte Cassino and the Benedictine Monastery atop it, finds it to have been foolhardy, a failure to recognize the Nazi willingness to wage total war, hiding in this instance behind the walls of a monastery from which to cut to pieces many Allied soldiers who for two weeks had struggled in vain to reach the summit, beset by enemy fire raining down on them from the monastery.

The desire to save it under such circumstances, while motivated by sentiment, was evil in its result, in that it placed an edifice of stone and mortar above the lives of men. Taking the hill was of paramount strategic importance for clearing the entire Cassino front of Nazis, and thus for taking the entire area below Rome and, ultimately, Rome itself.

In the end, there was no choice but to destroy what had become a Nazi fortress, no longer a monastery.

Wasn't this notion entirely correct?

To criticize the attack is simply to fall victim to old Nazi propaganda--tricks to pit the rational security interests of the Americans and British against their natural sentiments tender to such humanities as art and religion, tactics practiced by the Nazis since the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939.

"Speed-Up" takes notice of predictions, primarily from Chinese sources, that the war in the Pacific, being won apace against decelerating opposition from the enemy, would end sooner than estimates had previously asserted, perhaps before the fall of Germany.

Not stated by the piece, the implication was that, as Germany was expected to fall by the end of the year, Japan would surrender as well during 1944.

"Peace Money" reports that the Reconstruction Finance Corporation of the Government had announced its ability to make or guarantee loans for the purpose of reconversion of the economy from a war footing to peace. The editorial indicates that the primary effort by RFC would be for small and medium-sized businesses, as large corporations could, for the most part, take care of themselves.

"Hand-Biters" examines the strange new outlook of Labor as exemplified by the Carpenters' Union of the AFL. Meeting in Florida, it had denounced the New Deal as now having established too much government influence over Labor.

Having obtained most of their gains from the New Deal, Labor now wanted to preserve those gains but also return to a time of Republicanism where the free market could reign unfettered by government restriction.

Democratic Senator Josiah Bailey of North Carolina, not a New Dealer, had spoken recently as a seeming disciple of much the same philosophy now embraced by Labor, suggesting that Labor had been given too much reign over the country, essentially free to tax at will by establishing at will its dues for its members. Indeed, he said, Labor had become so strong as to threaten the Government itself.

The piece then asks rhetorically whether the Carpenters' Union and others of the same view within Labor would be prepared to cultivate to their cause more enemies of Labor within the Congress, such as Senator Bailey, to undermine the New Deal and return the country to the ways of the Grand Old Party.

The piece did not say it, but should have concluded with "Do you see?"

Dorothy Thompson suggests that the Lincoln Day speech of Governor John W. Bricker of Ohio, sounding as Warren G. Harding, uninspired and uninspiring, had amounted to little more than evidence of the Big Sleep by the Republican Party, still clinging to the notion that the community exists to serve business, not the other way about, that the war effort was testimony to the great tradition of private enterprise, neglecting the fact that it took government organization and government contracts to enable the war effort, which private enterprise had resisted with a passion right up to and beyond Pearl Harbor.

Governor Bricker had criticized rightly the vast bureaucracy, says Ms. Thompson, but neglected to take into account that its spread and constituency was quite the result of bi-partisan effort.

The Bricker line, echoing that of the Republican leadership, was to have the country revert to business as usual after the war. But that was no longer possible if another war was to be averted. Governor Bricker, concludes Ms. Thompson, was merely practicing Rip Van Winkleism--or that which Samuel Grafton was wont to call obscurantism.

Drew Pearson discusses the impact of wives on the promotions of military officers, especially generals, finds two theories extant: one, that it was of supreme importance to a officer's future how the wife behaved or to whom she might be related, citing as example General Pershing’s wife having been the daughter of an influential Senator during World War I, citing also General Patton's wife who demonstrated equanimity, offsetting the General's rough edges; or, the second theory, that the converse was true, that the spouse came to little in determining directly the officer's military promotion, citing Mamie Eisenhower as an example, unassuming and remaining in the background, or General Somervell, who was until recently a widower, or General Marshall, whose first wife had aspired to be an opera singer, fell sick for an extended period, and eventually died.

Samuel Grafton examines what should be done about Germany at the end of the war. He disfavors the proposals for war crimes tribunals, thinks it much too legalistic and suspending of judgment. He instead favors, as a part of the war, finally to defeat the enemy, even after the unconditional surrender, to dismantle completely all vestiges of the leadership and sub-leadership structures within Germany, as well as in Italy and Japan.

The famed trial lawyer, Louis Nizer, had written a book in which he proposed war crimes trials, but also favored summary execution for the top 5,000 Nazis.

Mr. Grafton instead proposes, in a concrete sense, to imprison or exile 100,000 of the leaders in each country, and in the case of exile, placing them under permanent guard, perhaps utilizing for the service volunteers from among the Poles.

In addition to Nuremberg, was not the partition of Berlin essentially an attempt to partition and confine within the Petri dish the prior catalysts of Nazism, civilian, military, and political, that part not made defendants at Nuremberg?

We think that the answer must be given indubitably in the affirmative.

It was, in the end, not completely such a bad thing, perhaps, this Wall, at least for a generation, until the little Nazis could learn to behave themselves. In any event, for all the vagaries of the Cold War, we have not thus far had World War III after nearly 66 years, a good track record, given the prior history of the world, characterized more by war than by peace.

The Reverend Herbert Spaugh again remarks on the regular attendance of church, even as the war raged around him, by General Sir Bernard Montgomery, finds it estimable and inspirational.

But, the Reverend has not remarked in awhile on the religiosity of General Patton, and we have to wonder when he might tell us, in unvarnished terms, of the General's own self-assessment of his daily Bible studies.

Perhaps, it will come during the Battle of the Bulge.

![]()

![]()

![]()