![]()

The Charlotte News

Thursday, October 19, 1944

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: Unconfirmed Japanese reports, indicates the front page, stated that the Third Fleet had entered Leyte Gulf in the Philippines, between Mindanao and Luzon, landing invasion forces on Saluan Island. Leyte is 415 miles southeast of Manila. The report was accurate. General MacArthur

Details remained sketchy.

The British in Western Burma had captured the Japanese stronghold at Tiddim, the point from which the Japanese had launched their invasion of India early in the year. Units of the Fifth Indian Division were the first to enter Tiddim.

Second Army British and American forces pushed back the Germans in the direction of Venlo on the Meuse River in Holland. West of Antwerp, also in Holland, Canadian forces were within two miles of Breskens, overlooking the entrance to Antwerp. Second Army forces were also advancing toward Amerika after having taken on Tuesday Venray.

On the Aachen front, the First Army resisted German counter-attacks as it continued to hold about half of the city, making new inroads to the northeastern sector.

The War Department announced that, as of October 3, American casualties in the war had totaled 174,780, of whom 29,842 had been killed, 130,227 wounded, and 14,711 missing.

The Russians, supported by 500 tanks, had penetrated East Prussia to the evacuated border town of Eydtkuhnen, 37 miles east of Insterburg. The Germans contended that breakthrough to engulf their lines from the rear, however, had been averted.

The front within the Suwalki Triangle had been extended from 30 miles to 45 miles in breadth.

Other attacks were taking place west of Riga in Latvia and southeast of Liepaja, the escape route for as many as ten German divisions in the Baltic region. Heavy fighting was also reported by the Germans in the area beyond Petsamo.

Another Russian offensive along a 60-mile front on the Narew River, aiming toward Danzig in Poland, was also taking place, according to German reports.

Approximately a thousand American heavy bombers struck Mainz, Ludwigshaven, and Mannheim in Southwest Germany.

The White House disputed Governor Dewey's remarks the previous evening which had labeled the Rumanian armistice as a full-fledged peace agreement fixing the boundaries and rights to possession of Bessarabia and Transylvania. The White House responded that it had only been a temporary military agreement, viable for the duration.

The hurricane which had hit Cuba and Florida had now passed through, heading north and expected to go out to sea. Cuba had suffered seven dead and 300 to 400 injured. Florida was spared any casualties but suffered some property damage as the storm took 24 hours to pass through the Miami area. Vacationing News Managing Editor Brodie Griffith provides his firsthand account of the aftermath.

On the editorial page, "Footnotes" makes note of two episodes in the campaign for the presidency: 1. In California, Wendell Willkie's 1940 campaign manager for the state, Bartley Crum, had formed a Republicans for Roosevelt club, denouncing the Republican proposed foreign policy as isolationist and nationalist; and 2. General Lewis Hershey, Director of Selective Service, who had contested Governor Dewey's contention that it was cheaper to keep soldiers in the Army to stem unemployment at war's conclusion, stated to the President that he remained nevertheless a Republican.

"An Issue" points out that Governor Dewey, if elected, would become the ninth President to sport a moustache. The Governor, himself, had injected the issue of his forelip, or whatever you call that space, into the campaign.

So, in support of the anti-discrimination against moustaches league, or whatever you would call it, The News includes the current and recently past world leaders with moustaches, several. Presidents Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Arthur, Cleveland, Harrison, Theodore Roosevelt, and Taft, all had moustaches.

So Governor Dewey posed no threat on the basis of his hirsuteness, rather followed in a long, distinguished line of the moustachioed.

But as to his resemblance to the man on the wedding cake...

"In the Red" comments on the fiscal responsibility risibly being counseled in Raleigh, in spite of the large surplus accumulated during the war. Because of anticipated smaller revenue bases after the war, it was no time to start squandering the surplus.

"First Reader" decries the effort of Democratic politician and lawyer William Rubin of Milwaukee who had filed a complaint with the FCC to get them to force Governor Dewey, Governor John Bricker, and Representative Clare Boothe Luce to retract several defamatory statements they had allegedly uttered against the President and correct them, and to require them to submit their manuscripts 48 hours in advance for scrutiny as to their truth.

Mr. Rubin had sought also to have the FCC void the licenses of radio stations which broadcast any such offending speech.

He was advocating these positions in the name of free speech. The editorial begs to differ, that it was an American tradition during a campaign that the out-party had the privilege of saying just about anything it wished of the in-party. And since the in-party appointed the members of the FCC, then it would greatly smack of political bias to undertake any such restraint as Mr. Rubin proposed.

Drew Pearson talks of the opportunity to win over labor which Governor Dewey's advisers saw available for him in his upcoming Pittsburgh speech. He had the chance to take advantage of the vulnerability of the President with the steel industry because no action had been taken to change the Little Steel formula.

During the invasions of Saipan and Pelelieu, a dispute had arisen between Major General Ralph Smith of the Army and Lt. General Holland Smith of the Marine Corps regarding the need to await artillery support before invading, General Ralph Smith favoring the safer approach while General Holland Smith was gung-ho to land on any beach at any time. Now that General Ralph Smith had been transferred to France, their particular argument had subsided, but the question still remained in the Pacific as to whether the landing forces needed more artillery support to avoid high casualties. The problem lay in logistics, that it was too risky to provide artillery support after the landing for fear of hitting U.S. troops.

Finally, Mr. Pearson reports that Martin Dies, retiring after 14 years in Congress, was booed when he sought to provide a Red-baiting speech against fellow Democrat FDR at the Texas state convention. He was the only speaker booed off the stage, suffering the endless boos for ten minutes before departing.

Friends of Governor Coke Stevenson were seeking to place Mr. Dies on the Board of Regents of the University of Texas. But the University president, Homer Price Rainey, the same who had extended the invitation to W. J. Cash to speak at the 1941 commencement, protested so loudly that the appointment to the Board appeared derailed.

Dorothy Thompson tells of the disturbing mob violence and harsh punishment otherwise in Italy directed against Fascists. In one instance, a mob had lynched and drowned the Roman prison director, Donato Carretta. In another instance, the director of the Bank of Italy, Vincenzo Azzolini, had been condemned to 30 years in prison. The lynching had been witnessed by New York Times correspondent Herbert Matthews who expressed horror, describing the violence to be worse than Fascism.

Ms. Thompson differs on the latter point, explaining that in 1925, five liberal lawyers had been drowned in the Arno River in Florence by the Fascists. The only difference was that the 1925 lynching was organized by the State.

Mr. Matthews had also protested the harsh punitive treatment of the bank director on the ground that his defense of following orders of the State was plausible. He had been accused of providing Italy's gold to the Nazis and providing other funds to the heads of the Fascist Government.

But the Fascists and Nazis thus far accused of atrocities had provided the same excuse, that they had been following orders on penalty of death for disobedience.

Thus was raised the question of the legality of inflicting such harsh punishments on subordinates for alleged war crimes. Maestro Arturo Toscanini had resolved the conflict in his mind when he decided to disobey Government requirements of obtaining a passport to leave Italy, on the ground that the Fascist Government was not legitimate. Eventually, third parties obtained for him a passport, but he had established the principle that it was honorable to resist the orders of a Fascist Government.

Karl Goerdeler had been recently hanged by the Nazis after severing his ties as a civil servant in Germany on the ground that the Nazi Government was not legitimate.

Ms. Thompson suggests, however, that since no international body of law existed which prevented the waging of war, it was questionable whether any legal basis existed on which even Hitler could be tried for war crimes. So all tribunals had to be established on revolutionary authority, not grounded in legality.

Ms. Thompson neglects in this analysis to recall that the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, of which Germany was a signatory, along with Japan and Italy, had outlawed war and had been violated by the three rogue Axis nations. That violation did form a basis for asserting illegality on the part of each of the aggressor nations in waging offensive wars, whether the defense was that they were "pre-emptive" or not. A pre-emptive strike is not available under the law of self-defense or defense of others; neither, therefore, should it be available under international law.

Countries which engage in pre-emptive strikes are to be considered by the world as rogue nations, terrorist nations, and should be dealt with accordingly at the international bar of justice—including the United States. No nation is permitted to do that which it wants merely by the fact of its having superior military power. That was the corrosive and subversive thinking which prompted, and, ultimately destroyed, Germany after World War I.

"Why not?"

Because it's wrong, stupid. Moreover, it ultimately backfires.

Marquis Childs, now in Portland, states that Oregon was too close to call in the presidential race, but Governor Dewey had a slight lead. Republican Senate candidate Wayne Morse, who would win the race and become a long-standing Senator, changing eventually to the Democratic side of the aisle, was the wildcard who might conceivably change the outcome in Oregon for Dewey.

That was so even though Republicans didn't like him. Mr. Morse, dean of the University of Oregon Law School and member of the War Labor Board, had virtually no money and no organization, but had struck a chord among voters and beat the incumbent, Rufus Holman, in the primary.

Governor Dewey, recognizing the political winds, counseled his fellow Republicans to get behind Mr. Morse. The CIO had endorsed him, despite the faction led by ILU head Harry Bridges voting to stay exclusively with the Democrats. Mr. Morse had also been endorsed by AFL.

The President had carried Oregon by only 40,000 votes over Wendell Willkie in 1940. With Oregon labor predicted to split 60-40 for the President versus 75-25 in 1940, the difference might be enough to enable Governor Dewey to win the state. And so the effect of Wayne Morse on marshalling this vote for the Republicans could not be underestimated.

Samuel Grafton, having just returned to New York after his cross-country tour, states categorically that he would vote for Franklin Roosevelt because he had been disturbed by some of the things he had seen and heard during his travels. Among them was the labor-haters of Oklahoma who were solidly behind Dewey, despite his support of labor and favoring the extension of social security to Government employees. Also among them was the isolationists who supported Dewey, despite his having trumpeted internationalism. The anti-Hillman campaign, equating Sidney Hillman of the CIO with Communism, also had an ugly ring.

In all, Mr. Dewey's coldness and calculation as a strategist to get himself elected, not solving the country's problems, was the centerpiece of his campaign. To garner enough electoral base, he had to court the various splintered interests despite the fact that they held views vastly different from those which he had enunciated.

Seeing all of this expediency and discord abroad the land under the Dewey banner, Mr. Grafton speeded back to New York in time to register in his home precinct so that he could proudly cast his vote for the President.

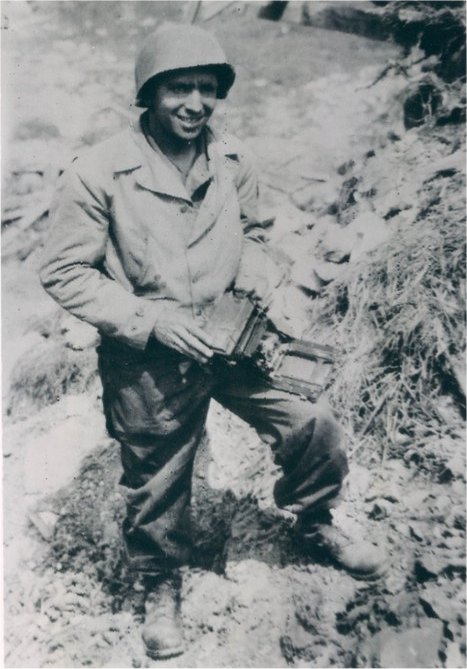

Hal Boyle, reporting from Germany on October 11, relates of a letter written from a widow of a soldier and photojournalist, Bede Irvin, of the Associated Press, who had died in combat at St. Lo in July. His wife had written him every day he was gone from home, for fifteen months. Mr. Boyle had known both Mr. Irvin and his wife well, and so felt obliged to quote from a letter she had sent to another A.P. photographer, thanking him for providing her the details of her husband's death.

She explains her difficulty in adjusting to the remote loss she had suffered. Now, she could write no more letters to her husband. She only had his letters, her memories, their photographs, and two

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()