![]()

The Charlotte News

Tuesday, January 25, 1944

THREE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

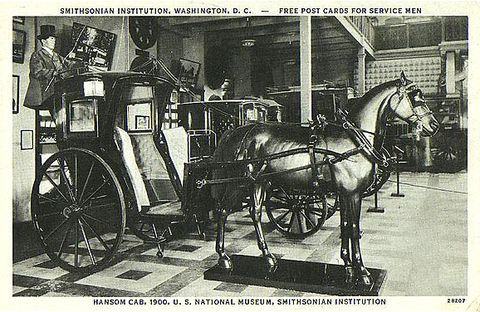

Site Ed. Note: We digress a moment to our note attached to Saturday's prints, to take a little hike back in time to the notes three years ago, associated with January 31 and February 3, 1938, as they related to buggies, or, more specifically, in the case of the February 3 note, to hansom cabs. We went in search of the specific hansom cab in the photograph provided us three years ago by a kind reader, that cab existing in spring, 1964 on display at the Smithsonian. We found it, as pictured below. (We had tried three years ago, but without success, probably because we were searching for the "buggy" exhibit rather than that of the hansom cabs.)

The hansom belonged to Alice Maury Parmalee, a member of Washington society. She was granddaughter to Matthew Fontaine Maury, the founder of modern geography as a science, a person who W. J. Cash listed in The Mind of the South as one of the true members of antebellum Southern aristocracy, based on learning and achievement from creative thought, not mere swellheadism, viz.:

One almost blushes to set down the score of the Old South here. If Charleston had its St. Cecilia and its public library, there is no record that it ever added a single idea of any notable importance to the sum total of man's stock. If it imported Mrs. Radcliffe, Scott, Byron, wet from the press, it left its only novelist, William Gilmore Simms, to find his reputation in England, and all his life snubbed him because he had no proper pedigree. If it fetched in the sleek trumpery of the schools of Van Dyck and Reynolds, of Ingres and Houdon and Flaxman, it drove its one able painter, Washington Allston (though he was born an aristocrat), to achieve his first recognition abroad and at last to settle in New England.

And Charleston is the peak. Leaving Mr. Jefferson aside, the whole South produced, not only no original philosopher but no derivative one to set beside Emerson and Thoreau; no novelist but poor Simms to measure against the Northern galaxy headed by Hawthorne and Melville and Cooper; no painter but Allston to stand in the company of Ryder and a dozen Yankees; no poet deserving the name save Poe--only half a Southerner. And Poe, for all his zeal for slavery, it despised in life as an inconsequential nobody; left him, and with him the Southern Literary Messenger, to starve, and claimed him at last only when his bones were whitening in Westminster churchyard.

Certainly there were men in the Old South of wide and sound learning, and with a genuine concern for ideas and, sometimes, even the arts. There were the old Jeffersons and Madisons, the Pinckneys and the Rutledges and the Henry Laurenses, and their somewhat shrunken but not always negligible descendants. Among both the scions of colonial aristocracy and the best of the newcomers, there were men for whom Langdon Cheves might stand as the archetype and Matterhorn--though we must be careful not to assume, what the apologists are continually assuming, that Cheves might just as well have written The Origin of the Species himself, if only he had got around to it. For Darwin, of course, did not launch the idea of evolution, nor yet of the struggle for existence and the survival of the fittest. What he did was laboriously to clarify and organize, to gather and present the first concrete and convincing proof for notions that, in more or less definite form, had been the common stock of men of superior education for fifty years and more. There is no evidence that Cheves had anything original to offer; there is only evidence that he was a man of first-rate education and considerable intellectual curiosity, who knew what was being thought and said by the first minds of Europe.

To be sure, there were such men in the South: men on the plantation, in politics, in the professions, in and about the better schools, who, in one degree or another, in one way or another, were of the same general stamp as Cheves.

There were even men who made original and important contributions in their fields, like Joseph LeConte himself, one of the first of American geologists; like Matthew Fontaine Maury, author of Physical Geography of the Sea, and hailed by Humboldt as the founder of a new science; like Audubon, the naturalist. And beneath these were others: occasional planters, lawyers, doctors, country schoolmasters, parsons, who, on a more humble scale, sincerely cared for intellectual and aesthetic values and served them as well as they might.

But in the aggregate these were hardly more than the exceptions which prove the rule--too few, too unrepresentative, and, above all, as a body themselves too sterile of results very much to alter the verdict.

In general, the intellectual and aesthetic culture of the Old South was a superficial and jejune thing, borrowed from without and worn as a political armor and a badge of rank; and hence (I call the authority of old Matthew Arnold to bear me witness) not a true culture at all.

--The Mind of the South, Book I, Chapter III, "Of an Ideal and Conflict", Section 11, pp. 95-97, 1941, 1969 ed.

Mr. Maury, however, as Cash did not disclose, perhaps not wishing to dilute the former's distinct academic achievement with unrelated social views common to Mr. Maury's time and place, led a movement at the conclusion of the Civil War to re-form the Confederacy in Texas or Mexico--being a mite, perhaps by then, tetched in the heed? (We gather this information, if memory serves, from the memoirs of Josephus Daniels, though we do not have the book at hand to prove indubitably the source, that being the result of the Ku, the Klux, and the Klan, Strutting Peacocks practicing relentlessly and, with bribe-induced impunity, Murphy's Law in one burg in North Carolina, who seem not at all hospitable to us for some reason, trying hard to set the brice, winding up in their own gin. But let us assure these Strutting Peacocks of that particular burg that there is nothing more which these beings insignificant can or may attempt to do to us, which they have not already tried, and at which they have not already miserably failed; and we assure them that they stand impotent before the Law of the Land, and before Nature itself in their inchoate attempts. We reiterate that there is no Power in a Limping Deacon. Oh, strike that. We do have the reference, after all. We had no idea.)

Mr. Maury re-settled for a time in Mexico with a band of former Confederates and established a small colony of expatriates, somewhat ironically, or is it? intermarrying with Mexican women. We say ironically, as miscegenation was quite common, quite obviously, on the plantation, perhaps in some ill-begotten, adulterated, and bastardized notion to unite a disunited nation, perhaps out of conscience, perhaps in the profundity of the fundamentals to produce unity of the elements out of the separate but equal qualities of the fuller's earth, perhaps, most probably, out of simple lust for the fleshy bosom, when confronted with no other alternative.

Mrs. Parmalee's Washington wedding, April 21, 1900, was attended by Chief Justice Melville Fuller, and the families of the other Justices of the Supreme Court, as her father, a judge, had been an Assistant Attorney General under former President Grover Cleveland, who had appointed Mr. Fuller to the high bench in 1888, a position in which he served until his death, July 4, 1910, the same year, just a couple of months later, in which the man whose years were bounded by Haley's Comet also left the earth, and for whom Chief Justice Fuller was sometimes mistaken, or vice versa, leading Mr. Clemens once, it is said, to provide his requested autograph in the stead of the Chief Justice.

Chief Justice Fuller was succeeded by Edward White, who, in 1915, if you recall, at first shunned as puerile the short-shorts of filmdom, then, when told of the very first feature film's noble and fuller purpose, to promote the glorious past of the Southern Confederacy and its post-war rebirth in the form of the grandly avuncular and nepotistic White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, suddenly, the story goes, embraced with full bosom "The Birth of a Nation", based on the 1903 and 1905 novels, The Leopard's Spots and The Clansman of Thomas Dixon, the weaver of the tale to Mr. White, leading to a premiere of the landmark, ground-breaking D. W. Griffith film before the full and fuller Congress, plus the entire Supreme Court, assembled together in congregation at the Capitol.

Ohio Senator Marcus Hanna, from Cleveland, campaign manager for William McKinley's 1896 initial, successful run for the presidency, also attended Mrs. Parmalee's wedding, presumably as a friend of the groom, a native of Cleveland, not to be confused with Grover Cleveland, Democratic predecessor to Republican President McKinley.

In any event, Mrs. Parmalee's mother was Betty Herndon Maury, who maintained a diary during the Civil War, not unique to her time. (cf. Mary Chesnut, and many, may live-long many, others) Mrs. Parmalee edited her mother's diary and produced it dutifully for publication, which, should you desire to read in fuller embrace of the brush to the side of the mind which she indited out of her less than candid self-equivocations educed from the quivering quill at the beck of her, no doubt, dainty limb, stretching unequivocally fuller in its course down to the very nerve endings at her fingertips, to motivate the flow of the India ink to wed itself inextricably from its corses to the paper, you must, in paying your devoirs to the author, realize the Belle Noir, and its complex, out of which most of these Southern aristocrats, especially those of the female variety, of the time wrote their innermost thoughts? scarcely being Belle-lettrists, mainly lettered in and by other belles constrained to their context, afraid the while of most things which went bump in the night, including the black boogey at the window, while the soft breeze, fragrant with the mashings, blew the curtain over her aching breast, desirous for the time of the touch of warmth from the fragrant apple blossom tree immediately below her second-floor window, though not fully knowing why, as a hound in the distance, sparked by the full moon, shredded over with a cloudy mist, bayed to the minor annoyance of the cat, aroused by her bedside to the call of the wild, which beckoned from afar--afar to the hills, the lonely green hills, and the marshes, the soaking wet, weedy winter-brown marshes, beyond, of Scotland or Ireland, depending on the break of the mind of the moment, as the guns, increscent in their iron balls fired with fiery, measured cadence, moving closer, ever closer, to despoil her sense of sanctity and grace, her foreordained understanding of forgiveness for earthly thoughts and consequence of her mastery when juxtaposed to those without, all uneasily expectant of dash--in sudden, blasting blasphemy issued from the marauding, uncouth, haberdasher Yankee intruder, dusty, sweaty, filthy, riding astride an equally dusty, gangly, and unthorough horse, replete with thoughts unclean of rapine and plunder, all fit only at once to do violence to her pedestal on which she posed daily in ritual countenance for those only within the confines of her finery-endued retinue, tradition of her aristocratic nobility in train, the better of the less she knew, all of which she could routinely, without strain, without the slightest bit of unerring reflection, each bright morning, as the birds greeted her with their special song, adorning the day with delight and fawning, see plainly, deeply within her lightly shining looking-glass eyes.

In any event, the hansom cab owned by Mrs. Parmalee, who passed away in 1940, was provided to the Smithsonian in 1920 by its owner who had used it to that time to transport her being around Washington City. And so, now we know the significance of that hansom cab which appears in the photograph from April, 1964, wherein appears also Mr. Cash's sister and some unknown boy, perhaps her student, though appearing a bit superannuated for the third grade which Mr. Cash's sister taught, unless, of course, the boy flunked a couple. (If so, that would have been no shame. Robert F. Kennedy had to repeat the third grade. It did not hold him back in life. His younger brother, Edward Kennedy, by his own insistence, once climbed the Matterhorn, in 1957.)

Incidentally, we do not know of any special significance attached at the time of the photograph to the particular exhibit of the hansom cab by the photographer or the photograph's subjects, as none has ever been imparted to us. It is simply as it is.

Moreover, we do not know whether the Maurys aforementioned were in any manner related to Army Major Maury, to whom Mary Cash Maury subsequently was wed about five years after the death of W. J. Cash, her second husband. Perhaps a genealogist can figure out that trail, if one exists, for what it may be worth. (Psychologists, especially of the amateur variety, however, beware of that into which you may step. You were forewarned, especially should you be possessed of the unfortunately confused notion that W. J. Cash took his own life rather than the better theory that it was taken impostumaceously from him by a network of Nazi spies operating at will, with impunity, in Mexico City in 1941, Mr. Raymond Clapper's April, 1941 beliefs imparted from observation and information conveyed with good intention to the contrary, notwithstanding.)

We make further note, in a separate context, in relation to the same note associated with the previous Saturday, regarding "Wastrel". Our last paragraph of that portion of the note, save the somewhat rearranged last phrase, was written, we kid not, before, mysteriously before, we ever laid eyes on two magazines, an issue of Everybody's Magazine, from January, 1908, an article by Zane Grey titled "Lassoing Lions in the Siwash", plus one immediately following, titled "Berlin and Its Burghers", and the issue of Life, dated March 25, 1946, the latter for both the article on the preservationist hunt for the cougar as well its immediately ensuing photographic essay anent the resumption of the bergamasks of Mardi Gras for the first time since 1941, banned, we take it, during the war for the possibility of permitting sabotage from behind the masks.

As we have before mentioned several times, it is sometimes ghostly dealing with this old print. Some other entity than, strictly speaking, ourselves, may sometimes grab our fingers and glide them unerringly along the paths of the keyboard. Musicians, no doubt, understand the concept well. We are aware of it when it occurs and thus become motivated to go in search of what it was beckoning us to the hunting of the snark for the day. Sometimes we impart it, sometimes we imply it, sometimes we simply let it go. Today, at some greater length than we intended initially, we imparted it.

That all said, the front page of this day indicates that unconfirmed Berlin reports stated that American forces of the Fifth Army in Italy had driven 18 miles northeast of Nettuno, point of Saturday's massive amphibious landing on the Italian coast, capturing Velletri, 22 miles from Rome, and nine miles from the Via Casilina, the road some 60 miles south to Cassino.

Fascist sources reported that the Americans had captured the entire thirty-mile stretch of the Italian coast from Nettuno to the mouth of the Tiber, and were threatening Ostia, port of Rome, three miles up the Tiber.

American reports confirmed only that the Fifth Army forces had advanced twelve miles inland from Nettuno, apparently to a point near the Appian Way, and had met little German resistance in the process. Anzio, the other landing point near Nettuno, had been captured. Forces were reported within a mile of the tracks of the Naples-to-Rome electric rail line.

An American reporter, Reynolds Packard, on the scene in the Nettuno sector at the time of the landings, indicated that Italians had informed him that the Germans had expected the operation to be initiated further north along the coast and had made preparations accordingly. That advice was confirmed by the reporterís observation of stacked mines in wooden crates rather than metal cases, suggesting only light German defensive preparations along the Anzio-Nettuno stretch of beach.

Don Whitehead discusses the vast change from two days earlier, when he saw a large, empty plain before which ships were landing, now bustling with Allied tanks, jeeps, and artillery, as small contingents of Germans were engaging American troops, yet, however, without any concentrated fighting. He describes one action taking place in the vicinity of Anzio at the Mussolini Canal, where American infantry units supported by tanks engaged German forces also supported by tanks, in an effort of the Allies to hold bridges taken in the initial thrust on Saturday and Sunday against enemy counter-attack launched Sunday night. After a night of fighting, the bridges were still held by the Americans on Monday morning, though four had changed hands three times during the long, loud night.

German forces were being shifted from the Cassino front to protect against the Allied drive toward Rome to the northwest. Nevertheless, heavy fire was being exchanged on the Cassino front, with American patrols having re-crossed the Rapido River.

The State Department, together with seven other nations of the Western Hemisphere, refused diplomatic recognition of the new government of Bolivia which had taken over in a military coup during December. The new government was said to have ties inimical to the Allies. The revolutionary nationalist movement which spawned the coup had vocally favored the Axis and had denounced the West prior to the coup, but had also come to power assuring that Boliviaís previous contract commitments to the United States for mining of tin would be recognized. The non-recognition policy with regard to Bolivia was not accompanied by any expressed form of sanction.

Behind the U.S. move, it was inferred, lay an attempt to strain the continued Axis relations of neighboring Argentina, the only country of the Western Hemisphere which still maintained a policy of recognition for the Nazi government in Germany. Presumably, the thought was that the new Bolivian Government would pressure the Argentine to sever its Axis relations so that both could live in harmony, economically and politically, with the Allies after the war.

Drew Pearson had reported recently that Argentina was still financially supporting Nazi spy activities, even within the United States.

Democratic Senator Frederick Van Nuys of Indiana, 69-year old chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was reported to have died. During his eleven-year tenure in the Senate, Senator Van Nuys had opposed many of the social programs advanced by the New Deal, as well as the 1937 court-packing plan. He had, however, supported the administration in its foreign policy, even prior to the outbreak of the war. As a progressive on racial justice, he had also co-sponsored anti-lynching legislation and legislation to outlaw the poll tax.

Hal Boyle returns to his regular space after a day of roasting by a colleague, to report of Lieutenant-General Omar Bradley, who he deems a shrewd selection for leading the American infantry in the invasion of the Continent to come. General Bradley was generally regarded as the favorite general of the G.I.'s, was plain in his demeanor, lacked any of the flamboyance and prima donnaism associated with General Patton and General MacArthur, (even if Raymond Clapper had found General MacArthur's reputation in that regard to have greatly outrun any reality behind the image conveyed by the American press).

General Bradley, from Missouri, had taught mathematics at West Point for many years, had an established war record in both Tunisia, where, under General Pattonís command, he led the Second Corps to victory, and in Sicily, also under Patton, where in 38 days he led the assaults which took Tronia, Randazzo, and Messina.

Cool, modest, confident, Mr. Boyle described him.

His military philosophy was simple: flank the enemy whenever possible and avoid frontal attack, a life-saving strategy.

The men called him "Our General", not "Our Blood, His Guts", as with his former senior commander.

He talked to his men as a peer, had what Kipling called, says Mr. Boyle, the "common touch".

He exerted his authority lightly and judiciously, insisted that his men at headquarters get along and without special perquisites.

He was also one of the best marksmen in the Army. Once in Tunisia, he had been consulting a map when a bullet whizzed past him. Unflustered, he took up his rifle and went in search of the sniper; wisely, the sniper resisted giving away his own position with another shot.

And some comforting news came from New York City. A detection crew, wearing earphones and carrying a steel rod, were hot on the trail of three missing tubes of radium which a patient had strapped to her by her doctor treating her for cancer. She misunderstood the doctor's instructions to wait in his office, instead left with the radium tubes still taped to her body inside a container, as she proceeded to the hairdresser. One of the tubes was recovered in the drain of the hairdresser's building. The other two and their container were still at large--and may be yet.

Beware, New Yorkers. These tubes are said to have long half-lifes. Stay in your houses and apartments. Do not take the subways. Avoid general panic. Stay away from all hair salons and any buildings which may have housed same in January, 1944. Do your research on your neighborhood accordingly.

Simply obtain plenty of duct tape and do with it what you will. Whatever you do, do not leave your homes without a good, working Geiger counter in your possession, or at least earphones and a steel rod.

On the editorial page, "A Victory" celebrates prematurely the ease with which the Allied amphibious landing of the Fifth Army VI Corps had taken place at Anzio and Nettuno on Saturday. It suggests that the leap-frog action, bypassing the natural defense barrier presented by the Pontine Marshes, was a brilliant maneuver saving many lives, and was successful as evidenced by the reports that the Nazis were fleeing Rome. It was, it further indicates, almost unbelievable that such a large force could be landed without detection by the enemy, further attestation of the increasing aplomb with which Allied operations were being conducted and further evidence of the decreasing efficiency of Nazi intelligence.

Nevertheless, it cautions that even such an unqualified success would be met with criticism by those who had long grown impatient with the sloth of the Italian Campaign, begun in early September with the landings at Salerno, after the relatively quick success enjoyed in the course of a mere five weeks on Sicily. These critics had been quick to assail the Italian Campaign as a waste after the disastrous Luftwaffe low-flying raid on Italy's Bari Harbor in mid-December. The critics wanted an assault on the coast of France.

Unfortunately, the initial success would be an illusion in this instance, the hope of a quick victory dashed, as the fighting bogged down in the crescent around Anzio and Nettuno during the ensuing six weeks of increasingly ferocious battle, continuing thereafter until the day before D-Day in early June.

"The Yield" sets forth from the Congressional Record an incisive debate regarding aid to India, led by Congressman Bloom of New York. You should read it for yourself, as the level of trenchant dialectic on this subject is such that it could not easily be summarized without loss of its finer points.

"DeGaulle" suggests, in irony, that a close eye be maintained by the Allies on General Charles De Gaulle for his latest advocacy that an immediate election be held as soon as France would be liberated by the Allies, not awaiting the return of the eighty percent of Frenchmen in exile, forced into German labor camps by the Nazis. The editorial asserts that such is a radical position, not awaiting the policy of expedience to take hold as in North Africa and Italy, to allow those who were in sympathy with the Nazis within Vichy to be dealt with sympathetically by the Allies.

Surely, it stresses again, this De Gaulle was dangerous to advocate democracy be asserted by the French citizenry immediately upon their liberation, before the politicians of Britain and America could move in to guide them and have their say over the future of France.

Dorothy Thompson opposes the concept of universal service championed by the Administration and Secretary of War Henry Stimson. She believes that elimination instead of the complex system of 25 different agencies regulating wages and price controls while passing anti-strike legislation and repealing the Smith-Connally Act, passed over the Presidentís veto, would serve better to accomplish the ends sought by national service, avoiding strikes while insuring that the work force would be employed at tasks best suited to each individual citizen's skills. She also suggests providing public broadcasts of the particular needs for employment in the various sectors of the economy.

Whereas Secretary Stimson had spoken of the soldiers' complaints regarding the country's labor strife and seeming callous indifference to the plight of those who waged the fight on the fronts, Ms. Thompson urges that the real problem was in educating the soldiers to the reality of the miraculous accomplishment of industry since the war had begun, with record production enabling simultaneously for the American civilian population few shortages of goods, save gasoline. She believed that in so doing, the soldier could be convinced that he was not going to return to a society of uncaring hedonists, but rather one which had engaged itself heroically to take up the gauntlet and achieve the production necessary to fight the war without the sacrifices normally expected from such a supreme effort in time of war. In that event, the soldier would not wish upon the society at large the same rigorous military discipline required of the soldier, "military socialism" as Ms. Thompson phrases it, required of the military for efficiency, but disastrous for a free republic.

Samuel Grafton finds that the Western Allies were splashing around Europe too much gray paint, keeping things bland and sterile, by seeking to counter-balance support between the stinkweed and the violets in countries such as Spain, France, Yugoslavia, and Poland. The reason for this tendency of bland décor was that the Americans and British, especially the Americans, would not have to live in and around the neighborhood of the result. But, for Russia, the results would be a daily environment with which to cope post-war. The Soviets were more interested therefore in preservation of the violets and elimination of the stinkweed, more interested in color than gray.

There was need, he concludes, for new décor and new decorum.

Drew Pearson relates of the Justice Department's investigation of a restraint on trade being practiced by a British trust in mining and production of mica. Without mica, there could be no radio, no radar, no detector devices, or electric gun controls. After World War I, it had been discovered that the British had restrained trade on mica to the point where there was just enough to accommodate the allies and keep it out of the hands of Germany and its allies, all in an effort to maintain a coign-of-vantage in the trade after the war. The investigation thus centered on whether the current practice bore resemblance to that of the earlier war.

The United States was a prime supplier of mica, but the resource had never been developed because the British had sold the world on the idea that its mica, chiefly from India, was of a superior grade. But that argument had been knocked down by tests, which found no difference in quality between the mica of India and that from the United States.

Efforts by Jessie Jones to establish production of mica in the U.S. had been placed in the hands of a manufacturer who had past ties with the British industry and thus was suspect of collaboration with the British trust.

Meanwhile, American manufacturers were utilizing special types of paper as unsatisfactory substitutes for mica.

Mr. Pearson also reports that the Library of Congress kept back issues of Esquire, along with other erotic reading materials, in a special file dubbed the Delta Collection, available only to adults, barred to adolescents.

Those under 18, therefore, should not bother the Librarian of the Library of Congress with your spate of sudden requests to view the back issues of Esquire. Your tender eyes might never recover, even should you somehow pull a fast one and tender a false identification. For the sort of female nudity which was then put forth in Esquire has never since seen the light of day--or so we've heard.

He next explains how lumber, used for some time to replace shortages of light metals such as aluminum, was now in such short supply as to be substituted by light metals.

That was probably bad news for the ladies at home, wishing a nice piece of new mahogany furniture with which to decorate the bedroom or living room, forced instead to resign themselves to some tacky aluminum monstrosity.

Raymond Clapper continues to detail the primitive conditions encountered by the Marines fighting on Cape Gloucester on New Britain, in the vicinity of recently captured Hill 660, so named, as he pointed out the day before, for its height of 660 feet.

Everywhere there were trucks and jeeps. The men he initially encountered were naked, bathing, washing clothes, setting up sandbags. He was informed by a lieutenant-colonel that when the observer encountered naked men, he knew he had arrived at the front. They would, further informed the colonel, remain naked until the nurses arrived, at which point they would don shorts. (You probably won't see that scene depicted just that way anytime soon in the movies. Anyway, let us hope not. It is quite alright to depict a man being blown apart by shrapnel, blown to bits, vividly and completely blown apart to bits, but let us not ever show his private parts intact, for that would be grossly offensive to the ladies and adolescents of both sexes present in the audience, not accustomed to such horror.)

The jeeps had to forge constantly through hub-deep mud and water, far worse than anything the men had encountered on Guadalcanal where the soil was sandy. No one much paid attention to heavy and incessant rain as the warm air quickly dried out clothes. The men wore whatever they deemed most suitable to avoid snipers, most opting for green coveralls. As their helmets were too cumbersome, they did not wear them unless they were at the front, three to four miles inland from "Yellow Beach" by the time Mr. Clapper arrived at that location by LST.

![]()

![]()

![]()