![]()

The Charlotte News

Monday, January 25, 1943

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

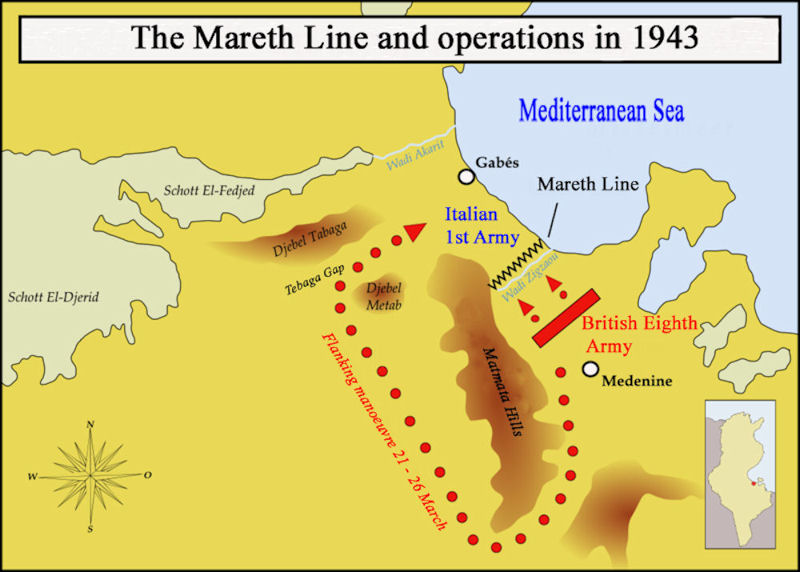

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports that the core of Rommel's remaining estimated contingent of 63,000 troops had ducked behind the Mareth Line, the "Little Maginot" of Tunisia, a series of fortifications erected by the French between the Gulf of Gabes and the Matmata Hills to the southwest, between the towns of Gabes in the north and Medenine to the southeast. An airdrome near Medenine, a town about 60 miles west of the Tripolitania frontier, had just been attacked by Allied bombers.

The remainder of Rommel's forces not yet holed up behind the Mareth Line were struggling along the Gabes coast from Tripolitania as the Tunisian forces of Col.-General Jurgen von Arnim, who had recently replaced the Rommel-disputed command of Walther Nehring, fought desperately to keep the roads along the gulf sufficiently clear to enable the rearguard troops to join the main force.

As evidence of American mobilization in the area near Gabes, along the Gabes-Sfax coastal railway and road, some 100 miles south of the area in which fighting had been steadily ongoing since December, in the region between Kairouan and Pont du Fahs, the American command had received a note from the Nazis asking, "Why won't the Americans come out and fight?" to which quick rejoinder to the R.S.V.P. was made in the form of a raid on Maknassy which captured 80 Nazi prisoners.

Supporting this theory of a massive attack to cut off Rommel's retreat along the Gabes-Sfax route, was the massing of American troops on the Algerian-Tunisian border 145 miles to the west of Sfax.

The front page story is continued on a second page, along with other continued stories, plus two maps. The maps contrast the vast differences in the pictures of the previous June and the present. In June, the German pincer offensive in the Ukraine and Caucasus was moving steadily forward with the goal of securing Stalingrad and then the Volga at its back in the north, and oil-rich Baku in the south, all as Rommel's forces sought to pummel Alexandria and capture the Suez Canal in North Africa. Now, the Russian counter-offensive of the previous two months, at present centering on re-capturing Kharkov and Rostov, thereby bottling up and capturing or killing over 500,000 German troops, a fourth of those remaining in Russia, was moving just as ferociously and unremittingly in the other direction, as the American-British-French fighting forces attempted to bottle up Rommel in Tunisia and eliminate the Axis from that theater.

Another communique meanwhile reported that the British Eighth Army, which had chased Rommel since October 23 halfway across Africa from El Alamein, continued its drive unabated toward Tunisian territory from Tripoli, which had fallen with little resistance into Allied hands Saturday following a scorched-earth retreat by its defenders.

A German thrust in the Ousseltia Valley, between Kairouan and Pont du Fahs, in Tunisia had been repulsed, taking away the attempt to occupy the Kairouan heights which would have afforded a sentry post to guard the coast road for Rommel.

The left Allied Libyan pincer, meanwhile, which had been approaching north from an area southwest of Tripoli, the Fighting French forces under General Leclerc, had obtained Jebel Nefusa, only 50 miles from the Mediterranean, with an objective of intercepting Rommel's retreat along the coast road to Gabes.

From Guadalcanal, it was reported that during the weekend six important hills above the Matanikau River were taken in the northwest sector of the island where Japanese troops still held sixteen miles of beachhead, north of Point Cruz. The hills collectively formed Mount Austen, the most prominent heights of which the soldiers had dubbed "Sea Horse" and "Galloping Horse", taken Saturday and Sunday after two weeks of steady fighting.

Below the heights of these hills, their capture having enabled Allied movement forward with impunity, lay the village of Kokumbona, three miles north of Point Cruz. Kokumbona was also therefore seized along with vital stores of the Japanese, as the Army forces recently relieving the Marines were quickly beginning to clean out the remaining Japanese forces on the island.

The capture of the village was deemed one of the most important of the Guadalcanal campaign as it had been through this village that the Japanese had landed reinforcements and supplies throughout the five-month engagement. Thus, the taking of the heights guarding Kokumbona had been a crucial assignment to finish off the Japanese occupation of the island--even if on December 27, the Japanese High Command had decided, unknown to the Allied commanders, that it would evacuate all remaining forces from Guadalcanal.

Also attacked on New Georgia Island to the northwest of Guadalcanal was Kolombangara, possessing a small airdrome supplementing the major airbase located at nearby Munda.

--Have a Coca-Cola on us. The pause that refreshes.

The Allies lost 250 in the two-week Mount Austen campaign while an estimated 3,000 Japanese soldiers were killed. These were the largest part of the remaining 4,000 Japanese troops on Guadalcanal estimated by Marine Lt.-Col. Chesty Puller in a press report appearing Saturday.

Marine Maj-General A. A. Vandergrift proclaimed without hesitation and as being beyond dispute that the Japanese had fought tenaciously and well in the Solomons, but added that, nevertheless, the American forces had effected a kill ratio of 10:1 against Japanese infantry and 7:1 against the Japanese air force.

In the Rostov Province of Russia, a key rail center was reported captured on the road to Rostov, 95 miles away. Two other forces were within 125 miles and 78 miles, respectively, of the steel center at Kharkov.

Moscow radio confirmed the capture of 3,000 more German soldiers below Voronezh, a total of 70,000 in the sector during the previous eleven days of fighting.

Berlin radio acknowledged the loss of Voronezh back to the Russians, which it claimed as captured the previous July 7, albeit a claim never acknowledged by the Russians.

The reports suggested that the Nazis had been pushed completely out of the area east of the Don River in the Voronezh region.

General MacArthur forecasted victory in the Pacific as a foreseeable event, given the proven success of transporting troops and materiel to the war front on the Papuan Peninsula of New Guinea, a campaign just concluded with victory.

General George Marshall was being reported by the press to be the likely choice for Allied Commander of the combined European Army forces, with British Vice-Admiral Sir Percy Noble likely to become chief of Allied naval operations combating the continuing pest of Axis U-boat activity in the Atlantic, North Sea, and Mediterranean.

To resolve the crisis in the muddled French leadership in North Africa, it was indicated that a joint British-American council would be formed to oversee the area, a council to which Generals De Gaulle and Giraud would be subordinated as immediate leaders. General De Gaulle, however, was quoted as saying that he would never assent to any such arrangement, that French territory had to be administered by the French, not by the British or Americans.

Each of these joint command reports apparently leaked out of the just concluded Casablanca Conference, a vague allusion to which is made in the article on the French leadership problem, as if the conference was yet to begin.

These good reports for the Allies from Guadalcanal, combined with the successful Papuan New Guinea operation gave credence to General MacArthurís contention that the war was going well in the Pacific and victory appeared on the horizon.

With the indication that a plan was being organized to achieve a major thrust into Europe to end the war in that theater within the ensuing year, the news combined to provide ample ground for optimism by the public that World War II would be over before spring, 1944.

It was thus not surprising that it was also reported from Washington that scores of bureaucratic agencies were engaged in post-war planning, dubbed "powarps".

Manpower administrator Paul McNutt and Secretary of Agriculture and Food Administrator Claude Wickard announced the intended formation of a 3.5 million person volunteer farm labor corps to be deployed to assist the farmers beset by the dramatic labor exodus to the more lucrative war industries of the city during the previous year.

And, Canadian Vice-Admiral Percy Nelles indicated that the Nazis were supplying U-boats in the Atlantic for longer voyages via freighters loaded with gasoline and torpedoes, and, presumably, other vital supplies such as food. These freighters were dubbed the "milk cows" which, said Vice-Admiral Nelles, were supposed to cow the Allied forces but didn't.

These "milk cows", incidentally, should not be confused with the Russian terror weapon known as the Rebbaj Gnickow, also said at times to be deployed by the other Allies as well, instilling fright in any Axis soldier for its ineffably fierce, nasty teeth.

On the editorial page, Burke Davis takes issue in "The Alarm" with the stance adopted consistently by Dorothy Thompson, reiterated in her editorial of the day, favoring stress on shaping democracies in the process of wresting nations from Axis control, rather than waiting until the end of the war. Mr. Davis finds this view to be myopic in its self-promoted hyperopia.

He is inclined to the notion that the military commanders had their hands enough full with war chores and should not also have been constricted along the way to smoothing divided political factions of various stripes into unified democratic folds, lest the war be lost, quand même, as French republican ideals were being restored during the winning.

Ms. Thompson, however, believed that so adapting societies, grown accustomed to Nazi-Fascist oppression, back to democratic ideals was a sine qua non for winning the war and preserving peace after the war, that war and the post-war environment were continuous functions of history growing out of and into one another and not separately categorized points on a history class timeline. To dichotomize the process between military occupation and establishment of political stability on democratic foundations, she opined, invited the same disaster which followed World War I and led directly to World War II, that the failure of post-war planning had led America to curl back into its isolationist down after providing the trench-fighting cannon fodder significant to the final thrust which won the war.

Who was right? Could Ms. Thompson's premise have been carried effectively into operation while the war was being fought? Was it, eventually, after France was liberated by the Allies in the summer of 1944?

Raymond Clapper addresses the suggestion, favored by the former isolationists led by Senator Wheeler and by the farm bloc led by Senator Bankhead, that the other Allies, predominantly over-populated Russia and China, should bear the brunt of the fighting, leaving to America its better focus on food and industrial production to provide the manufactured goods and raw materials for the war effort, to better achieve thereby the goal of its role as the "arsenal of democracy", as President Roosevelt had deemed it a year earlier in the wake of the disaster of Pearl Harbor.

Mr. Clapper thinks otherwise than the view of Senators Wheeler and Bankhead, adopting the stance of the Army that such a limited role for America would lengthen the war by depriving the fronts of needed American personnel abroad.

Who had the better of the argument? Could the war have been won in Europe without American participation beyond that already provided in the North African offensive? Was the tremendous sacrifice of American life in Italy, and on D-Day and in the liberation of France truly necessary?

But, even if one could imagine General Patton's tremendous campaigns without American soldiers behind him, what proper role could America have claimed morally in restructuring post-war Europe along lines necessary to prevent World War III? and without any notion at the time that on the landscape of 1945 would arrive suddenly the atomic bomb to alter all diplomatic equations.

Chapter 19 of They Were Expendable begins the harrowing tale of the only two operational MTB's remaining in Lieutenant Bulkeley's Squadron 3, PT-41 and the newly re-vitalized PT-34, fresh from dry-dock, seeking to intercept and eliminate the Japanese destroyers and cruiser reportedly in the neighborhood of Cebu and Negros Island--on the scene apparently because the Japanese had become aware of the seven inter-island steamers loaded to the gills with supplies, to be protected by a complement of twelve Flying Fortresses and several P-35's up from Australia, ready to provide relief to the embattled Army contingents defending Bataan and Corregidor.

However untested the renewed PT-34 boat was, its patched hull boards unexpanded, Lieutenant Kelly was nevertheless ready to go when Bulkeley came to him with the prospective mission.

The importance and danger of the mission were communicated by the fact that the skippers were provided the radio frequency to contact American air support at dawn should they find themselves in a tight spot.

The crews arrived at the designated enemy alley at around 11:30 on the night of April 8. By 11:55, they had made visual contact with the Kuma-class cruiser, a ship of 5,100 tons with six-inch guns, supposed to have four seaplanes aboard. The two boats sought to encircle the ship before it spotted them, Kelly going toward the bow as Bulkeley headed for its quarter. Each boat fired two of its four torpedoes; all four missed. Bulkeley then circled in an arc and fired his other two, one making contact with a big splash but no explosion. The cruiser, however, had already increased speed, apparently spotting the wake of the missed torpedoes.

Out of torpedoes, Bulkeley attempted to distract the cruiser with tracer fire while Kelly maneuvered across the wake of the ship to fire his last two torpedoes to its starboard side, as the cruiser marked down PT-34 in its searchlight. Kelly fired, the last two torpedoes any of the squadron would fire in the Battle of the Philippines.

As he turned and sought to get away, a destroyer gave chase. Caught in between tracers weaving overhead in crossfire from the cruiser and the destroyer, Kelly set PT-34 on a zig-zag course to escape the deadly cannonade. Just as the situation began to look dire, an explosion erupted as one of the torpedoes, fired in an overtaking course, hit home. Then, in quick succession a couple of seconds afterward, came the second, right into the engine room. Kelly saw the cruiser's searchlight slowly dim to black and knew the ship was doomed.

Bulkeley watched as the cruiser sank within twenty minutes while he was busy warding off three other destroyers on his tail.

Kelly, meanwhile, had to take evasive action to avoid the fourth destroyer, two more than had been reported from aerial reconnaissance prior to the mission. According to Bulkeley's count, PT-34 endured 23 salvos of 5½-inch shells, any one of which striking home would have split the plywood hull asunder. Kelly cut a path astern of the destroyer to lose it and was able to duck away out of its searching beams.

After making good his escape, he looked around the deck to see his port gunner and cook, Reynolds, bleeding from wounds in his throat and shoulder.

Kelly had no ability to call in the air strike against the destroyer as his radio antenna had been shot away.

Bulkeley managed to speed from the area and escape the three destroyers tailing PT-41, finally finding safe haven just before dawn in a shallow cove, one which was six miles from any depth sufficient to accommodate the destroyers. He and his spent crew slipped quietly into death's analogue and slept the day away drifting complacently in shallow tropical waters.

Lieutenant Kelly, 28 years old at the time, would be awarded the Navy Cross for his bravery in the face of enemy fire in sinking the cruiser.

But his safe haven was yet to be found, on the night of April 8-9, 1942.

And, remembering the quote this day from Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., obviously provided to Clark Kent the notion last week that he had to depart from Lois on the street and run back into the building to retrieve his hat to keep from catching a cold. But, still, we have to wonder how this exigency even came to be when all the while Lois was in the elevator and Superman was Up, Up, and Awaa-aay in living color seeking out The Voice in the highrise, on the thirty-third floor. Doppelgangers, we suppose.

In any event, Mr. Montgomery, presumably of Montgomery Ward, has Superman trapped in his offices, imputing to him co-conspiracy with The Voice, seeking the spread of Nazi propaganda.

Since Friedrich Nietzsche created Superman as an answer to man's overcoming and downgoing, an insensate constant without fear or feeling--in other words, a Nazi, even if Mr. Nietzsche probably had something else entirely in mind--, we tend to lean toward Mr. Ward's viewpoint. But, we shall see Tomorrow whether Superman can talk his way out of this one.

Meanwhile, Lolita begins to comfort the bee-sting blinded Red Ryder.

You see? We told you so. He does plainly, however, have a defense in his Flynnesque trial surely to follow: "Doc, I was blinded by the honeybees--if you know what I mean."

And, returning to that second page, the one with the maps, we have to wonder whether NBC executives, in their recent ponderously equivocating fractured Philippic, anent the shuffling of nighttime lords of hosts, perhaps, with assiduity, studied the ad put forth by the Charlotte Hardware Co., and then took comedy quite a mite too seriously.

![]()

![]()

![]()