Change to solid gold background

| Change to beige | Change to pale solid green | Change to whiteClick browser refresh for Mercury background | If in Netscape, click flashing numb-pun to change

If in 3.x browser, go to links at bottom of page to change

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA

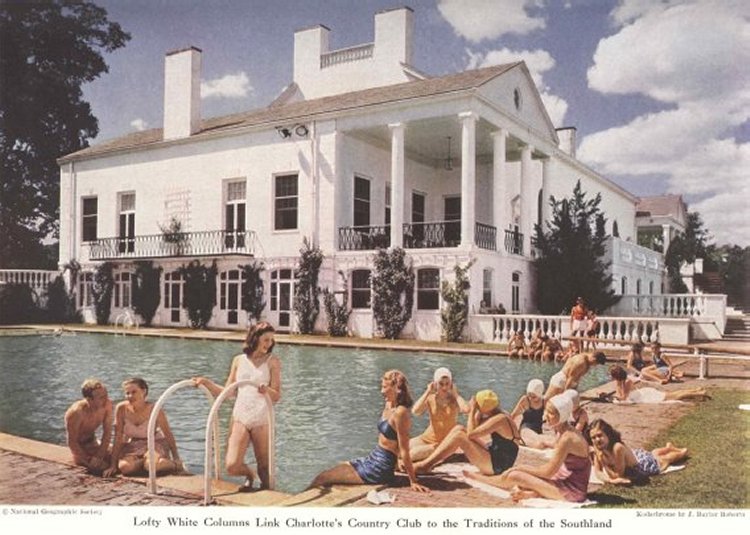

Two views of Charlotte, the subject of "Calvinist Lhasa", appeared in an article in National Geographic, "Tarheelia on Parade", by Leonard C. Roy, in August, 1941, the month after W.J. Cash's death in Mexico City

Site Publisher's Note: This fifth Mercury article which saw the light of day in April, 1933 saw Cash unleashing his barbed lash on Charlotte; the Mercury issue quickly sold out in the "old Torytown", as Cash lampooned it. Cash picked on Charlotte probably because then, as now, it was the largest city in North Carolina--then approaching 100,000 in population, which mark it would proudly celebrate surpassing in 1940--and the largest city in the region where Cash grew up in its shadow, some 50 miles to the southwest.

Cash had worked on the Charlotte News for a brief time in the mid-Twenties and would finish his newspaper tenure there from 1936-1941. In fact, the bulk of the final version of The Mind of the South would be written in the "Queen City" while he lived downtown on Church Street in the still extant tan-brick Frederick Apartments, just a block from where Jefferson Davis first met with his cabinet at the formation of the Confederacy. (A plaque on the art deco facade of the Frederick today commemorates Cash's three-year stay there--virtually the only place he ever lived in Charlotte. After his marriage, he lived for six months at a different residence until leaving in May, 1941 for the fateful trip to Mexico.)

Charlotte seemed abuzz in the latter Thirties with young cognoscenti and literati. At the same time, just across town, the young Carson McCullers, (whom Cash would meet briefly in early 1941 in Atlanta while visiting as the guest of Margaret Mitchell and her husband, John Marsh), was beginning to write The Heart is the Lonely Hunter and Reflections in a Golden Eye, during her year or so of residence. During the period 1939-1941, the young John F. Kennedy, who would publish to great fanfare in September, 1940 his expanded college honors thesis, Why England Slept, would visit Charlotte numerous times, including the weekend immediately preceding the publication of The Mind of the South. Kennedy went for his health, and on the latter occasion, to find a ghost writer for his father's memoirs, something, he told a friend at the time, he hoped would be in the manner of North Carolina native Walter Hines Page's well-respected two-volume autobiography. (Source: The Search for J.F.K., by Joan and Clay Blair, Jr., (N.Y., 1976), pp. 103-107) But whatever attracted such people, including Cash, to Charlotte in these later tumultuous days had apparently not impressed Cash by 1933, when he wrote this article, just as Franklin D. Roosevelt ascended to the Presidency.

Indeed, though not as pointedly, he continued to criticize Charlotte in 1940, identifying it only as a "Southern city of a hundred thousand people, which serves as trading center for a million people", in the latter pages of The Mind of the South, complaining about the lack of a decent library or even a regular clientele for classical music--as the largest music store owner claimed to Cash only four such customers. (Mind of the South, pp. 418-421 [subsection 21], 1991 ed.)

Cash mocks Charlotte in "Calvinist Lhasa" as a "citadel of bigotry and obscurantism", a "blue-nose posed on the face of Carolina" possessed of a Presbyterian God "impossible to match anywhere in the South or even in the ranges of interstellar space", and Scotch-Irish who are "the very peak and capsheaf of their kind". (And why, then, "Lhasa"? Probably because for centuries, through Cash's time, Lhasa, the holy city of the Lamaist monks in Tibet, was known, because of its zenophobic exclusionary policy toward non-Tibetans, as "The Forbidden City".) Cash uses Charlotte essentially as an every-city of the South at that time, a town growing out of a rural landscape, suffering from excessive gaudiness and parvenuism--the new Babbitt part doing battle with the traditional Calvinist or Fundamentalist part within the same populace or even within the same person--still wearing its overalls underneath its tophats and tails, dreaming perhaps of the Never-never Brobdingnag and the ladies in farthingales of the plantation-era, and wanting to create in reality as closely as possible every nuance of the dream sequence, but with the whole effect ending as something similar to the image conjured by the price tags dangling from Minnie Pearl's new Sunday hat.

Just what Cash would make of Charlotte today is anyone's guess. Cash would likely still find fault with some of the things with which he found fault in 1933. He would not be at all surprised that the likes of Jim Bakker had found a partially friendly haven there from which to broadcast his P.T.L. Club in the 1970's and 80's; but would no doubt be astounded and pleased that the Observer broke the story that led to the end of Bakker's empire and, with it, the eventual virtual end of the popularity of money-bagged televangelism.

He would also find other things to provide optimism, especially in the political and cultural-literary arenas. Charlotte has grown to nearly a million people, has a sure-enough 60 story bank skyscraper and a spanking new professional football stadium smack-dab in the center of downtown, just a few blocks from Cash's old Frederick. A modern multimedia center next to an open green called Freedom Square occupies a large expanse now, just down the block from his old apartment. And the immediate area of the Frederick is now mainly surrounded by handsomely gentrified sand-blasted old brick townhouses. Cash no doubt would positively cheer at the short perambulation from the Frederick to a bright new award-winning library--even open on Sundays for the "bookkeepers" of the town--stocked with plenty of books and all the Wagner, Bach, and Beethoven Cash would have needed for contentment, plus a special collection of materials on W.J. Cash in its well-stocked North Carolina room, not to mention all of Shakespeare's plays produced by the BBC on something called video tape--in fact a collection which rivals or surpasses even such urban libraries as San Francisco's recently remodeled Romanesque masterpiece.

(Pardon the digression but the comparison is deliberate as Bank of America, founded a century ago by A.P. Gianini as a small family enterprise in the City by the Bay has just merged this year with a Nations Bank out of Charlotte to form the bigger B. of A, with its headquarters to be in this once beatified bastion of Toryism. Time will only tell how mates such a merger of seemingly vastly different cultures--the one more apt to spawn attendees to a tribute to Jerry Garcia on Thursday, Patti Smith reciting Allen Ginsburg on Saturday, and a Shakespeare play in Orinda or an exhibit of Monet at the DeYoung Art Museum in Golden Gate Park on Sunday--and all this by the same person, mind you--, while the old Tory is more apt to send forth those who revere Richard Petty or Garth Brooks or, for the more literate, college hoops and Squirrel Nut Zippers, than Shakespeare or paintings any day of the week--but yet with the cognoscenti still finding their way to ferret out a local production of old Will's Measure for Measure and the one Bosch or Brueghel on display at the local art museum when they have the spunk and need to do so... But both cities would find ample crowds for a Rolling Stones or Paul McCartney venue on Saturday and a Panthers-49er's joust or Michael Jordan ballet on Sunday; so, in that, at least, there will be initial and immediate commonality.)

And while Cash would likely find nothing but an array of contumacious typeface for the horn-honking stuffed miasmic morass of confusingly intersecting broad boulevards now belting the city, he would no doubt find both amazement and pride in the fact that Charlotte elected an African-American mayor a few years ago, (an architect whose current offices look toward the Frederick, a block away, and parted now only by a newly erected edifice owned by Nations Bank tending toward obscuring the once very visible Frederick)--a mayor who later admirably contested Jesse Helms for the Senate in North Carolina both in 1990 and 1996.

In the final analysis, Cash liked Charlotte; he admitted to visiting often even long before he lived there. (Both of his slightly younger brothers moved there in the late Forties and both died there in the Nineties, one having been a successful orthodontist and the other a successful small business owner.) Ultimately, Cash criticized only that which he wanted to make better when he could see the potential for betterment from the criticism. In that--as with the South and his fellow Southerners--Cash expressed his profoundest respect for this small city which he prodded like one would mock and prod a beloved little brother slow to catch on to the finer mysteries of life. Maybe, just maybe, the criticism helped over time, at least as to some aspects of life there.

And what would Cash think of the turn-of-the-next century computer terminals at this fancy new library with most of all the great works of literature in the public domain crammed onto a five-inch shiny disc one could read at will off a typewriter keyboard with a little cubic foot movie screen attached to it, along with whole encyclopedias one can hold in the palm of the hand, the Charlotte Observer daily projectible at will on the little movie screen and accessible throughout the world? The PC, the Mac, terabyte servers displaying satellite photos of the Frederick in one yard resolution from interstellar space? Hard to say... As his wife recounted, he could not adjust his bulbous fingers even to the portable typewriter he bought for the fateful final trip to Mexico and instead preferred the bulky iron-encased Underwood typewriter on which he wrote throughout the Thirties; nor did he ever even own an automobile. But it is known that his younger sister, a school teacher, marvelled at the new computer technology prior to her death in 1987 and Cash was always in favor of machines which increased the potential for learning, as long as they did not measurably interrupt or curtail the creative, intuitive part of the process. So he would probably find all of this stuff pretty worthwhile as tools at least to remove some of the drudgery of sticking keys and ink stains with which he put up daily sixty years ago at the now long-gone Charlotte News.

Yet, even in 1998, had he lived

so long as the last of his two brothers who died that year in

Charlotte, you would be liable still to find Jack Cash with his

bald as ever pate somewhere over under the shade of the brim of

his Panama hat, under some maple tree on Freedom Square, looking

sleepy while being wide awake, inkstains aplenty on his fingers,

cussing a little as the keys stuck, wishing he could climb to the

top of that maple and run with Pan, and still probably pecking

away some critical statement or another in fine humor on the old

black Underwood.

In this October, 1998 photograph of downtown Charlotte looking across Church Street, Cash would recognize the foreground view of the founders' cemetery just three blocks from his Frederick Apartments building, but would see nothing familiar in the background in which the 60-story NationsBank building and other skyscrapers rise to the Southern heavens.

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA

BY W. J. CASH

IT IS a magnificent and outrageous irony that the town of Charlotte, the capital of Mecklenburg county in North Carolina, should set up to be the original birthplace of what used to be called, without conscious cynicism, American liberty. According to the chief legend of the place, the men of Mecklenburg, foregathered in the log courthouse which stood at the corner of what nowadays is Independence Square, declared themselves free and independent of the wicked George III on May 20, 1775--more than a year, that is, before the Continental Congress enacted the Declaration of Independence. As to the truth of this, I am not able to say. No one, indeed, is. It rests wholly on the testimony of those who represented themselves to be the chief actors in the proceedings, and that testimony was delivered long after the Revolution was safely fought and won. But with its truth or lack of it, I am, after all, but little concerned here. What really concerns me is the astounding contrast between the town's legend and its character

For, in its essence, Charlotte is an old Torytown, a citadel of bigotry and obscurantism--one of the most hunkerous, if not, in fact, the champion for hunkerousness, in the South generally, and certainly by long odds the champion of North Carolina. It is possible, in truth, to chart the flow of civilization in that great State by the simple device of conceiving it as a thundering field of battle whereon the justly famous State university at Chapel Hill gallantly defends the standards of intellectual integrity against the ferocious assaults--no, not as one might think, of everything and everybody else in sight, but chiefly, and almost wholly, of this very town of Charlotte.

Elsewhere in North Carolina the spirit which reaches its apogee in the university has been getting in its work, and for a long time. For instance, there is Greensboro, a town which for two decades has been clearly emerging from the old grooves. To say that it has completely emerged or that it is likely to do so soon, would be to go far beyond the facts. Its liberalism, in so far, at least, as it is not a vague and amorphous thing, is the property of relatively small groups, and its advances are intermittent: it may be questioned, indeed, that there have been any notable ones since the day, some years ago, when Gerald W. Johnson folded up his desk in the office of the morning newspaper and crossed the Potomac. Nevertheless, the tendency unquestionably exists; it would be difficult, and maybe impossible, to make a lynching there or to stir up a pogrom for any of the more imbecile of the ancient superstitions. And the same thing may be said, in varying degree, for other towns in the State.

Charlotte, of course, is not its only Tory stronghold. But if

Raleigh and Wilmington, for example, are also to be set down as

exponents of the old Kultur then they are only passively

so. In them is a great

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 444

defeatism. The Goth, they know, is upon the Flaminian way. The Hun swings southward from the infidel universities of the North and makes himself at ease within the Tar Heel gates. Tomorrow--next week--in time--, they understand with a great certainty, their world will end. Meanwhile, they will not think on it, they will not fret themselves with contending against the inevitable. They will doze in the sun, they will pull all their jugs, they will make love to their charming women, they will cultivate serenity and a kind of elaborate, but still somehow homespun, Tar Heel grace, thanking an inscrutable God that the day of wrath is at least not yet.

But the Toryism of Charlotte is militant. At its heart is a vast and nearly insatiable zeal, an immeasurable itch for blood. The town breeds crusades as a pup breeds fleas. Out of it have proceeded every one of those forays, not only against the university but also against liberalism in general, and not only against liberalism in general, but even against elementary sense and decency--every one of those forays which have from time to time in recent years elevated North Carolina, blushing and cringing in some vague realization that she was somehow being made to seem ridiculous, to the front pages of the nation. And on its stage have been enacted the more atrocious, at least, of the lynchings (I use the term figuratively, of course: all North Carolina may be said practically to have abandoned the sport in its old raw and vulgar form of frying the black brother) which have disgraced the State in the same period. Do I seem to exaggerate? Then get down the newspaper files and examine the record for yourself.

There, in 1926, was cooked up the Committee of One Hundred, which had for its aims the enactment of a monkey-law and the throttling of the university's appropriations unless it agreed to swallow the law without a whimper and to fire every man of any honesty from its faculty.

There, again, in 1928, was born the Anti-Smith Committee. There arose its captain and most of its members, and out from Charlotte went most of the warnings that the Pope was hovering off Wilmington with thirty thousand sail and a hundred million wops--all that idiotic clamor which in the end brought NorthCarolina up slavering to avert the Coming of the Scarlet Woman.

It was from Charlotte again--as all informed Tar Heels guessed even then--that, in 1929, its handmaiden, Gastonia, drew the inspiration and the courage to resort to shooting and burning against the Communist strike-leaders who had set themselves down in its virgin precincts, and so turned what was essentially farce into tragedy. And it was in Charlotte, as everybody will remember, that these strike-leaders were at last formally and legally lynched.

It was Charlotte, and almost wholly Charlotte, which stood on

its head and tore its shirt and screamed for gore, when, in 1932,

Norman Thomas and the Negro poet, Langston Hughes, appeared on

the lecture platform at the university. And it was in Charlotte,

and almost wholly in Charlotte, that, immediately thereafter, the

Tatum petition--which demanded that the Governorof the State

forthwith expunge from the university library the works of Darwin,

Freud, John Watson, Bertrand Russell, and, indeed, of everybody

who has had anything to say since 1800--was hatched. The authors

and promoters of that document were all Charlotteans, and of the

284 signatures, at least three-fourths were drawn from the town

or its satellite villages.

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA 445

II

Well, and what is the explanation? What ails the place? Wherefore all its Christian zeal? How does it happen that this town of the Mecklenburg legend not only remains impervious to the spirit of liberalism but pants to put it down?

Probably I have already suggested the answer in calling it a Tory town--but that plainly calls for a great deal of explaining. Certainly the casual observer would be hardput to it to discover anything of the traditional Tory there. For, by an irony but a little less striking than that of the legend itself, Charlotte is one of the two or three greatest exponents of Progress in the whole Southern country. Forty years ago a shabby village, horribly dogged and torn by the poverty of Reconstruction, it has grown up to be the keytown, both industrially and commercially, to the valley of the Catawba--the cotton-mill country par excellence in Dixie--and the metropolis of both the Carolinas.

Physically, it is nearly Middle Western. The South survives in the yellow wash of the sunlight; in an occasional burst of flowers and vines about the shacks where the coons live in the alleys back of Friendship Baptist Church; in two or three blocks of moribund old houses set back in shaggy lawns along North Tryon street where it descends to the Seaboard depot; above all, in the sedate beauty of the Old First Presbyterian Church, which sends up its single gracile spire from a park of great trees in the heart of the downtown district. But, for the rest, the scene is supremely commonplace and modern--a matter of the inevitable crown of so-called skyscrapers, of a girdle of factory villages and sub-divisions, of warehouses and spur tracks, of chain stores and filling-stations, of countryclubs and snooty suburbs with their faces new-washed, and of an infernal din which, when the citizens are in a really patriotic mood, when they bear down on their automobile horns with true civic zeal, is comparable to nothing save Hell or Chicago's Loop.

All of which is to say, of course, that Babbitt swarms and pullulates. As realtor, as cotton-mill sweater, as banker, above all as the Duke Power Company, which has its principal offices in Charlotte, he overshadows and overruns the scene. Nowhere else in Dixie is the hierarchy of Rotary more firmly established, and nowhere else is the Chamber of Commerce more an oracle, nowhere does it whoop more grandly for the Future.

But Babbittry, per se, does not explain Charlotte--not adequately, at any rate. The fact is, indeed, that, if one leaves aside theYankee he-men who infest the place in hordes, the local Babbitt is apt to be a very different fellow at bottom from his compatriots in Buffalo and Omaha. Scratch under his hidedeeply enough and you find, not a visionary, but a Tory; you find, that is to say, that what counts primarily in his make-up is what counts primarily in the make-up of Tories everywhere: the past--that, in reality, he is simply the natural, and maybe even the inevitable, outcome of his town's past.

And this past? Primarily and fundamentally, a matter of the

Scotch-Irish and their dour Presbyterian God. There are other

gods in practice in Charlotte, certainly--Methodist, Baptist,

Holy Roller, Catholic, what you will. And there are other blood-strains--mainly

English and German. But either these other gods are servile

understrappers, aping the ways and opinions of the Presbyterian

God, and worshipped only by stuffy bourgeois and the brassiest of

nouveaux, or they are outcasts, kept under the surveillance of

the police,

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 446

and adored only by the utterly damned. And these blood-strains, wherever they are not amalgamated to the Scotch-Irish by marriage or long tradition or both, are the blood-strains of long generations of green grocers or of cotton-mill peons lured in from outside. Only Presbyterianism and the Scotch-Irish really count.

A hundred and ninety years ago, a band of them reached the lower valley of the Catawba from Pennsylvania and Maryland, and set up seven fanes in honor of their God. And a hundred and sixty years ago, the seven congregations came together in the wilderness and built a courthouse and, a few steps away, an eighth fane--and the town was born. In that beginning, I suppose, the God of the place was simply the God of Presbyterians everywhere. Nor, so far as I know, is there evidence that these Scotch-Irish differed noticeably from the norm for the Scotch-Irish generally. They were enormously strait-laced, they looked upon industry and the getting of goods as pious exercises peculiarly pleasing to Heaven, and they had all the smugness, all the complacency and selfrighteousness, natural to the belief that they were handpicked for Grace. They exhibited all these qualities in the measure common to their race.

Gigantism, however, set in immediately and has continued through all the years since, with the result that Charlotte today is a sort of holy town, a Lhasa of Calvinism, a Gargantuan blue-nose posed on the face of Carolina. Its God is not merely a Presbyterian; he is such a Presbyterian as it would be impossible to match anywhere else in the South or even in the ranges of interstellar space. And the Scotch-Irish of Charlotte are no ordinary Scotch-Irish but the very peak and capsheaf of their kind.

All this is the outcome of vast and primal forces. In the first place, there was the backwoods. Down to the beginning of the present century, the valley of the Catawba remained a relatively isolated section, and in the first seventy-five years after its settlementit was almost completely cut off from the world. Between it and the Eastern seaboard stretched a vast and nearly uninhabited waste, which yielded but slowly to the advance of the plantation. The Confederacy (by which I mean all that economic and social order which centered in the plantation) did not come to Charlotte until late; the first cotton-gin in Mecklenburg was not set up until about 1830. Accordingly, the local Scotch-Irish, never very susceptible anywhere to modifying and restraining influences from outside, found themselves completely removed from such influences. In Charlotte the lid was off. There their Presbyterianism could flourish as in vacuo. And there all their tribal qualities could shoot up in neoplasmic abandon.

The country fitted with the people. Before them was the forest, old, untamed, pagan--the obvious symbol of Satan. To mow it, to burn it in great heaps, to bend the earth to their will--that was at once to slake their lust for acquisition and to acquire favor on high. And the proof of that favor was that they prospered. None of them had any money, but all their logbarns swelled with grain and all their flocks and herds multiplied after their kind, for the earth was fecund with the accumulated mold of centuries. And so inevitably they waxed in piety, and so inevitably they sank deeper and deeper into complacency.

If now and then the world swung close, then it only served to

confirm them in their way. The Revolution rolled southward and

Cornwallis came along to set up his headquarters. But the fates

and the Scotch-Irish conspired against him, and presently he was

hastening north to Yorktown. And

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA 447

the Scotch-Irish, forgetting the fates, remembered only that their God was obviously a very puissant fellow, only that the redcoat had clubbed them Hornets for the ferocity with which they had defended their razorbacks. Afterward, gold was discovered, and newcomers trooped in--rough and hearty Germans, an Italian who called himself a count, and a beef-eating Englander with a lackey and two wenches. But the Germans married Presbyterian gals and set up for storekeepers, the Italian took himself off sadly for more promising fields, and the Englander, abandoning lackey and fancy women, took to saving souls.

So when the Confederacy at last heaved across the skyline, it found Charlotte already far gone in Calvinistic giantism, already definitely a holy town--and completely adamant against the thin stream of paganism which was properly a part of the classic Confederate tradition. But that is not to say that it was adamant against the Confederacy in general. Far from it. With glad hosannas, the Scotch-Irish fell upon cotton culture and the coining of shekels from the hide of the black brother, seeing in them but the natural reward of their virtues, but another proof of the favor of their God. And with equal joy, they seized upon the central notion of the Confederacy--that of aristocracy--and made it their own.

III

Certainly, they had not been aristocrats in the beginning. On the contrary, they had been the simplest of men: peasants, smiths, artisans of one kind or another, practically to the last jack. And certainly, they had not got to be aristocrats in the valley of the Catawba, though, of course, several families had emerged as local magnates.

One family in particular--with a grand Scotch clan name--had so prospered that one of its members had built himself a two-storied house of flint rock. But that was the limit. Everybody else lived in houses of logs; and Washington, riding this way on his junket to Charleston, could find nothing resembling gentry to entertain him.

But none of this deterred the Scotch-Irish. All about them, everywhere in the South, other peasants and smiths were turning aristocrat overnight, so why not they? With cotton came wealth, and with wealth political power, and with political power social ambition. As well as they might, they adopted the manners of the Virginians and the more polite Carolinians to the east. Then the greatest family--that one of the clan name, of course--gave a Governor to the State, and the thing was practically done. All that remained was to endow themselves with a sufficiently imposing tradition and a sufficiently dazzling ancestry.

This was easy. For there, ready to hand, was the legend of the Mecklenburg Declaration. The greatest family, recalling that it could boast the author and the chief signers of this immortal instrument, seized hungrily on the half-forgotten story, routing all its dotards from their chimney-corners to set down their memoirs as to just how it happened. And the other signing families naturally hastened to follow suit. It was a little embarrassing, of course, that the document itself could not be produced, but then there had been a fire.... And if Mr. Jefferson and his Virginians sniffed and hooted in high contumacy, then what ailed them, obviously, was ignoble envy. The Charlotte gentry could and would stare them down.

Nor would they stop there. The greatest family, observing its

grand clan name,

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 448

turned back and proceeded to adorn itself with kings--traced itself to David II of Scotland, and beyond David to the Bruce, and beyond the Bruce to Alexander I. Here again, of course, the lesser families followed eagerly. In time, indeed, it got so that a family which could show only one king was accounted but little better than white trash--with the natural result that the supply of kings presently began to run out. So with the years, the Scotch-Irish got themselves back to Kenneth McAlpine, and beyond Kenneth to Scota, and in the high melodramatic time which followed the Civil War they abandoned Scotland altogether and took to the Lost Tribes, carried themselves back to David, the son of Jesse, and beyond David to Noah, and beyond Noah to Adam and the quickening breath of God. I do not exaggerate; they literally did it.

And so, by dint of fiercely asserting their aristocracy, they half-began to convince even the snooty Virginians and wholly convinced their own imaginations. But, of course, they did not really become aristocrats; of course they did not succeed in investing their subconsciousness with that peculiar coloring which was the secret of the few genuine aristocrats the South could show. In their hands, indeed, the notion of aristocracy became simply a new and powerful sanction for their ancient standards and ways.

In all this, it is difficult not to see the hand of their peculiar God. Certainly it smacks of predestination and manifest destiny. For if Charlotte had really achieved the standards of the Confederate aristocracy, or even if it had only really attempted them, then it plainly could not be what it is today. If, in the years when the cotton-mill was rising on the land, the town seized the ascendancy, and became, not only a great industrial hive but also merchant and banker to all the country within a radius of a hundred miles, if today it is the great Babbitt town in Tarheeldom, then it is primarily, as it seems to me, because of the character which it brought to the new order.

IV

The Scotch-Irish-Calvinist Kultur was admirably adapted for the business in hand.Without exception, every Southern town which has risen to eminence in the new order has been more or less under its sway. And in Charlotte, where it reached its apogee, it naturally worked most perfectly.

There the coming of Babbittry involved no revolution, nor even any conflict. There were no heart-breaking last stands and massacres, no Bourbon houses in bitter, shuttered mourning for the advent of Gradgrind and Bounderby--nothing of that struggle and defeat which has accompanied the industrialization and commercialization of such a town as Charleston, of every town where the classic Confederate culture had really taken root--but only hosannas and Te Deums. There the past flowed into the present soundlessly and without a jolt. There the gentry not merely received the Yankee go-getters with open arms, but themselves, and to a man, turned Babbitt without a qualm or a pang and without an iota of change in their proper character--took to Rotary with all the loving gusto with which a duckling takes to water, with all their ancient zest for acquisition and all their historic confidence that they were laying up treasures in heaven.

And here, of course, we have the last great justification.

This is the final secret of the town's unbending adherence to its

ideals, and the key to its militancy in Toryism. The thing works--and,

even in

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA 449

these days of Depression, it pays. Yesterday and today, it has made and makes uniformly for the prosperity and security of those who rule in Charlotte. What is more, it promises to keep on making for them indefinitely. Do the peons in the mills begin to rise and protest that to work for five dollars a week--as they do work these last bitter days--is too much for human flesh and blood? Then what better answer than the Presbyterian answer that it is all God's will, ordained from the first day, and so to be endured quietly lest complaining draw down fire from Heaven? What better answer than the Scotch-lrish answer that, if the peon is exceedingly ragged of behind and lean of belly, it is because he is shiftless and unthrifty, because he and his fathers have succumbed to sin and sloth?

Tradition and economic interest join hands and fuse as they have rarely done elsewhere, in the South or out of it. The very Chamber of Commerce can reserve its proudest boasting, not for the biggest cotton-mill, not for car-loadings, nor even for the high-spouting fountain on the Duke estate, but for the slogan: After Edinburgh, the Greatest Church-going Town in the World. In fine, save for the little matter of its manners, Charlotte is well-nigh perfectly integrated. Theology and the hog literally make one flesh, and that, so far as the natives go, without any alloy of dreadful hypocrisy to sully their innocent confidence. To question Babbittry is to question God, and to question God is to question Babbittry, and to question either. . . And so, plainly enough, liberalism, the university, whatever questions and challenges in North Carolina, must be destroyed. Plainly enough, Charlotte is called on to take up the role of Defender of the Faith, to fare forth, shining-eyed and unafraid, under the standard of the Cross and the Feed-bag, in the happy knowledge that Heaven will give the victory.

The consequence of all this, however, is appalling for the town. If its culture is not actually on a level with that of the Tshi speakers of West Africa or the natives of Nias, it is nevertheless of the same general order. There is the same enormous concern with decorum, the same vast body of taboo and penalty, the same terrified truckling to shaman and rain-maker. Life is one continuous blue-law. Does a handful of naive mamas, hearing that their high-school daughters are necking gloriously at public dances, arise to suggest timidly that maybe chaperoned dances at the high-school itself would be better? Their petition is thunderously vetoed by the town clergy, and they (the mamas) themselves are pilloried in public bulls as so many Messalinas. Do the bookkeepers of the place, having no automobiles to escape in like the Presbyterians, think life would be more bearable if the public library was opened to them on Sunday afternoons? They are denounced as agents of Satan and the library is shut up tighter than ever. Does the Junior Chamber of Commerce, in its youthful ingenuousness, take pity on the proletariat and suggest Sunday baseball? The holy men proceed to ram through a law banning Sunday tennis on private courts and even Sunday bridge in the parlor, and are only persuaded to retreat from this position by the earnest prayers of the chief Babbitts.

Intellectually--but, in the very nature of the case, the word

has no applicability. One takes what the pastor of the First

Presbyterian Church is thinking, one takes what the Duke Power

Company is thinking, and one arrives at the editorial page of the

Charlotte Observer--the very living mirror of the

Charlotte mind and a catechism for all true believers. "The

Bible,"

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 450

it appears, "is the best textbook of biology." "The bulk [sic] of the Depression," it appears, "is all in the talk." The cotton-mill barons, it seems, are Little Flowers, and the Duke Power Company a sort of orphan asylum for cold, wet, hungry kittens. And the Carolina cotton-mill peon, it seems, is the happiest of all men. And the arts? And books? Ah, yes, the arts and books! A matter of no import to be disposed of in a puny weekly column sandwiched between tales of the tall deeds of obscure Babbitts--a matter (until quite recently at least) to be handed over to a spinster whose aesthetic yardstick is her Fundamentalism.

Such stuff is significant of the mental status of Charlotte, it ought perhaps to be said, not because everybody is inherently so stupid as to be unable to rise above it, but because nobody or nearly nobody (the town has two or three somewhat querulous and rabbitty "liberals") ever dares rise above it. These people are not without the elements of mind. Take them out of here and they often distinguish themselves. Two of the three presidents who have made the University of North Carolina what it is arose from Charlotte. Even in the town itself, it is possible, and pretty often, to discover individuals who, as individuals, are at once sensible and charming. Behind the privacy of their locked doors and over their jugs, they reveal, not only flashes of intelligence but, sometimes,--and however improbable it may sound--even a streak of something perilously like poetry.

In mass, however, they are a people chronically and greatly frightened--of themselves. Let the word come down and they become simply a herd; their idiosyncrasies and their private convictions slough away and they click into line like so many marionettes, slide through the grooves of their Kultur-pattern with all the inevitability of Hardy's dynasts in the coils of the Immanent Will. If any man hesitates, he is lost. If he belongs to the upper orders, he finds himself in a prickly situation in which it is impossible to live and so has eventual resort to potassium cyanide; if to the lower, he is branded a Communist and handed over to the humors of the cops.

Thus life degenerates to a dreary ritual of the office, golf, and the church--becomes nearly unbearably dull even for Presbyterians not wholly pathological. A superior dozen or two find refuge in classical learning or the Flemish primitives--something utterly and safely removed from any possible contact with their dally lives. Others, turning neurotic, go in for romanticism and live out their days in dreams.

A melancholy picture, no doubt--maybe, in truth, a shade too

melancholy to be left so. It may be that, even as I write, what I

say begins to be a little untrue; it may be that even this last

citadel of Calvinism in Tarheeldorn begins to crack--that the

latest sorties testify, not to strength but to decay. Certainly,

there are strange signs to be seen. For one thing, there is a

Little Theatre now--a Little Theatre which, whatever its

shortcomings as a temple of art, has at least had the courage to

go on with a play which the town pastors had forbidden. For

another thing--a wandering Spanish fiddler, armed with all that

capacity for faith which distinguishes his race, sat down in

Charlotte a year or two ago to organize a "symphony

orchestra." To say that his faith has been justified would

be to exaggerate unduly; nevertheless, at the last hearing, his

performances were enabling him to eat regularly and to wear a

pair of sound pants--surely no mean success for a fiddler in

Dixie.

CLOSE VIEW OF A CALVINIST LHASA 451

More promising yet is the fact that, in June of last year, the town rose up and, in the teeth of the whole body of holy men, repudiated its own first citizen, the uproariously dry Senator Cameron Morrison, to vote overwhelmingly for an even more uproarious wet. More encouraging still is the story of the Charlotte News. When the Tatum petition appeared last August, this sheet, following its immemorial policy of echoing the Observer, published an editorial whooping it up. Then the editor resigned and one of the owners, a young fellow, took up the task, frankly repudiated the former stand, and published a series of editorials panning not only the petition but the town's bigotry in general. It was a brave and decent thing to do, for the signatures of the owners of the two chief department-stores, and, indeed, of other principal advertisers, were on that petition.

Finally, there is the younger generation.Tradition, shaped in the days when the institution was a Presbyterian stamping machine, still sends it to the university to be educated. Most of its members, it goes without saying, are immune to ideas, but the number of those who succurrib tends to increase. They take it out largely, as yet, in drinking loud and violent damnation to all bluesnouts and in flaunting their amorous antics. Maybe, however----

But this, all of it, is, after all, only maybe. I have reported the town for what it is: the chief enemy of civilization in the Near South.

Let the future answer for itself.

Go to Top of Article Go to Top of Page

Go Home Go to 6th article: "Buck Duke's University"