Three Articles on W. J. Cash

Go to article 2: "A Prisoner in Time", by Bob Smith

Go to Article 3: "A Footnote on W. J. Cash and Southern Paradoxes", by James McBride Dabbs

Site ed. note: In February, 1967 when this article appeared, the Knopf Publishing Company was about to release the first biography of Cash, by Joseph L. Morrison, W. J. Cash: Southern Prophet. Morrison, originally from New York City, had obtained his undergraduate degree at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill where as a senior he saw Cash speak in May, 1941. After serving in World War II, Morrison obtained his masters degree in history at Columbia and his Ph.D., also in history, from Duke. He then began his teaching career at the University of North Carolina in the School of Journalism where he remained until his untimely death from a heart attack in 1971. Professor Morrison published several books on North Carolinians, including two on Josephus Daniels, Josephus Daniels: Small-d Democrat, U.N.C. Press (1966), and Josephus Daniels Says ..., U.N.C. Press (1962). He also wrote articles for American Heritage and other journals.

A Biographical Detective Story

by JOSEPH L. MORRISON

(Reprinted from the Red Clay Reader, Vol. 4, 1967)

THE REPUTATION of Wilbur Joseph Cash, an obscure North Carolina newspaperman in life, has continued to grow every year since his suicide in the summer before Pearl Harbor. Sales of his The Mind of the South have approached the six figure mark in hardcover and exceeded that in paperback. College bookstores, in particular, have found the book a favorite with succeeding generations of collegians, each group of young people coming newly upon W. J. Cash with an air of "wild surmise."

And who, exactly, was this "Jack" Cash that we should now make him prescribed reading (as we increasingly do) in college courses? Simply put, Cash was a Southerner who "psychoanalyzed" his native South, who revealed its extraordinary talent for self-deception, and who warned that the South had better wake up and come to terms with the Twentieth Century. Since World War II, and especially since the thrust of the Negro revolution in America, Cash's prophetic book has come into its own. It has been cribbed from, plagiarized, and imitated. It has been cited and quoted endlessly. Nobody has excelled it as a feat of historical interpretation, sweeping in scope, detailing the Southern experience in its totality. Historians are generally agreed that studies of the South today must begin where W. J. Cash left off.

Cash was not one for the passionate gesture or the white-hot polemic; as a Southerner he wrote more in sorrow than in anger. Yet, in his own dispassionate way, he ruthlessly exposed the historical falsity of every Southern myth he had had to unlearn in the course of his own intellectual growth. Not only was the Old South a myth, he

![]()

![]() Cash's

favorite picture of himself.

Cash's

favorite picture of himself.

(Site publisher's note: In its original format, this picture was, of course, the intact version of the picture which appears at the frontispiece of this site. The picture became mangled in the scanning process and, well ... the irony was too fine to pass up. Cash would have likely "whooped" at the thoughts conjured by the "abstract" version, as in fact he despised this picture, taken only a few months prior to his death. Professor Morrison misunderstood (or was having a private joke with readers) when he described this as Cash's "favorite". In fact, when the picture accompanied a Time Magazine book review in February, 1941, Cash remarked to his wife, Mary, that he thought it rather made him look like a gangster. She reminded him that he had only himself to blame for sending the picture to the Knopfs. (Source: W.J. Cash: A Life, Bruce Clayton, p. 167.) His true favorite seems to have been the photo taken of him by Alfred Knopf in 1939, the one showing his bald pate and a broad grin.)

demonstrated, but so also was that New South so loudly proclaimed in the 1880's. Moreover, Cash laid bare the emotional crises that led Southerners to invent these myths and to insure their survival. He revealed the factors bearing upon class consciousness; the relation one with the other of religion, race, rhetoric, romanticism, leisure, and the cult of Southern Womanhood; also, the patterns formed by demagoguery, violence, paternalism, and evangelism. And on the very last page of his book Cash reverted to Topic A, criticizing his native South for ". . . above all too great an attachment to racial values and a tendency to justify cruelty and injustice in the name of those values."

W. J. Cash was born in Gaffney, South Carolina, on May 2, 1900, raised there and in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, worked mostly in Shelby and Charlotte, North Carolina, all being within seventy-five miles of one another. His background was orthodox Baptist, but an element of individualism at his alma mater, Wake Forest College (also Baptist), and his prodigious independent reading led him to his two-decade quest for "The Mind of the South." He tried teaching

RED CLAY READER 14

for two years before giving it up as a bad job, then gravitated to newspaper work in the hope of moving ahead some day to the role of novelist. His writing plans were hedged in by ill health, stemming apparently from a hyperthyroid condition he developed in young manhood, so that he was forced to make his bid for economic independence by writing from his parents' home in the depths of the Depression. Even so, by 1936 he had won a contract from Alfred A. Knopf for The Mind of the South and had published a spate of articles in H.L. Mencken's American Mercury.

In late 1937 Cash got a job as editorial writer on The Charlotte News where, the following Spring, he met the young woman who was to become his wife. Jack agreed with Mary that they would put off marriage until he had completed his manuscript, a chore that was not wound up until the summer of 1940. One of the factors slowing the manuscript's completion was Cash's obsessive outrage at the totalitarianism then spreading over Europe, a matter about which he repeatedly editorialized in the News. He and Mary were married on Christmas Day, 1940.

When, as Cash's biographer, I first undertook my round of "saturation" interviewing, I found to my dismay that this man, dead for a quarter century, had grown into a legend. A mythology had sprung up around him, a mythology that had confronted every other scholar interested in Cash. My biographical task would require that I "demythologize" W. J. Cash, that I play the role of part-time detective. What lay in store for me became clear when I found that three stories relating to Cash's suicide had been credited in various quarters without anyone ever having bothered to check further. The three may be stated substantially as follows: (1) Cash was murdered by Nazi agents; or (2) he decided to end his life because he was suffering from an incurable brain tumor; or (3) Cash was the victim of .somebody's foul play because, when he was found hanging by his necktie, his feet were touching the floor. In one way or another I have since satisfied myself that these stories are false.

It turned out that demolishing the third myth was easiest, because here I could turn to data accumulated on the subject of suicide. Can the feet of a suicide by hanging--I had to ascertain--touch the floor? The answer is yes, and, in the majority of instances, the feet do touch the floor. The authorities point out that a suicide standing on the floor has only to double up in order to cut off his supply of oxygen, and, when he relaxes in death, his feet invariably touch the floor. In fact, I learned, a would-be suicide who does not use a chair--and Cash used none--cannot succeed in his attempt without his feet touching the floor. Furthermore, I found in none of the contemporary official documents relating to Cash's death anything about his feet touching the floor--because this was apparently irrelevant--but somehow a student writer "reported" it as a presumably sinister fact in the Wake Forest Student Magazine of November, 1959. Of such stuff are myths made.

The second myth, that of the "incurable brain tumor," is so much alive and kicking that Ralph McGill of the Atlanta Constitution, who picked up the story quite innocently, repeated it in a recent letter to me. I learned that the story gained currency at Cash's funeral, where it was spread by word of mouth, because Mary Cash had wired home--thinking to spare Cash's parents further pain--a white lie: "Doctor thinks brain tumor may have been responsible." I learned, furthermore, that the same story was invented independently at the funeral by Cash's old friend, Everett Houser of Shelby, who told me as much. There was no "incurable brain tumor." In an autopsy performed upon Cash and required by Mexican law--as explained by U. S. Ambassador Josephus Daniels to Cash's father in a letter of .July 3, 1941--there was no report of a brain tumor.

Cash's heartbroken parents could never believe that a complex of physical illness and psychological pressures could have brought their brilliant son to suicide. The "Nazi murder" story obviously got started among those who, like Cash's parents, simply could not bring themselves to accept the fact. The nagging conviction of foul play harbored by John William Cash--he long outlived his son and died only a few days short of his ninety-second birthday--took published form as late as August 14, 1964, in the Cleveland Times of Shelby. The interviewer quoted John Cash about his son: "'It was publicized that he committed suicide, but he didn't,' says the father firmly. He has always believed that his son's death was caused by foul play, thinking it connected with his strong editorial and newspaper stand against Hitler and Mussolini. "

What did I find, however, in the contemporary documents? Ambassador Daniels quite exploded the "Nazi murder" story in a letter to his son Jonathan, one of Cash's friends, to whom the ambassador wrote on July 10, 1941: "She [Mrs. W. J. Cash] must have known his mind was unhinged when he was obsessed by the thought that the Nazis wished to get him. It was purely imaginary,

RED CLAY READER 15

for nothing of the sort occurred." That Cash's death came by his own hand the official documents make quite clear, and these reports were not completed until a thorough police investigation had been made. Even the first news story out of Mexico City about Cash's death, an Associated Press dispatch dated July 2,1941, reported without qualification: "Commander Alvaro Basail, of the Capital's Radio Police Patrol, asserted Cash committed suicide."

Destroying the Cash mythology is one thing, but trying to

explain why Cash committed suicide is entirely another. I pursued

that explanations partly by consulting with three separate

psychiatrists, each unknown to the others, in preparing a chapter

entitled "Why?" in my forthcoming biography of Cash.

The subject is altogether too complex to pursue here. But I

conclude with two observations: first, that the mind that

conceived The Mind of the South, even if

neurotic, was of sunburst clarity; and second, that, like every

truth-seeker, W. J. Cash gleaned his bits and pieces of truth at

the expense of his bitter toil and agony.

Site ed. note: At the time of publication of this article, Bob Smith was a young staff member of The Charlotte News, the newspaper for which Cash worked in the mid-twenties and latter thirties. Smith had authored a study on the integration of Virginia's schools, titled, They Closed Their Schools. He had worked on other Southern newspapers and had been a contributor of articles on folk and jazz music in Down Beat.

by BOB SMITH

(Reprinted from the Red Clay Reader, Vol. 4, 1967)

IN THE FALL of 1960 Cash's book blossomed on the reading lists in Harvard's Yard like some lush tropical growth. Everywhere the young in mind wanted to know about the South and, of course, only Cash could tell it like it was. The book was instant revelation to a generation of yearlings who had never been south of the Jersey Turnpike; they picked about it for cryptic wisdom as though sifting through runes, or they swallowed it at an indigestible gulp like one of those dreadful purgatives of Eighteenth Century medicine, sustained only by faith. One young man in Psychology of Social Processes, taught by an expatriate Virginian, confessed to me that Cash had helped him know himself for the Yankee that he was.

I was astounded but not entirely displeased. I was a guest on the campus, an academic Fellow with journalistic credentials and I found myself--who had always been suspect as a Northerner down South--accepted as a genuine Southerner in the North. Unconsciously I reverted to historic type: I caught myself deep in mythic dream at cocktail parties, loud to the point of brashness in my laughter, sweet-mannered beyond believing, prideful, quick to the heroic gesture. They asked me if the South was still Cash's South and I smiled uncommunicatively. The truth was that I did not know. Feverishly I dug out my battered copy of The Mind of the South and read it again.

It is a remarkable book by any standards but perhaps, like Gulliver's Travels, its truths are so large that they are best perceived from a distance. I had read it first two years earlier when it seemed that the South was ready to go to war with the nation over the Supreme Court's school desegregation decision. I had inspected every tree in that forest, looking for a way of understanding the trial the South proposed to bear. To my mind, Cash's people were figures etched sharply but in the near background. They were vivid enough in their own context but things were so much more complex than that now. The Yankees-stole-the-silverware old ladies, the gentleman with patches on the pants under his longcoat, the courthouse hell-of-a-fellow--these were archetypes fixed in the past, useless except as reference points. And Cash's Negro, Cuffey, "lamentably inclined to let his ego a little out of its chains and to relapse into the dangerous manners learned in carpetbag days"--was he not dangerously close to stereotype? So I thought but yet was powerfully moved by that first reading and could not tell why.

A year later I had stood amidst the honeysuckle in a Prince Edward County, Virginia, field, at the Hillsman House, which had been converted into a Union hospital during the battle of Sailor's Creek, in the company of five men who called themselves Defenders of State sovereignty and Individual Liberties. In the name of all that was Holy and Southern they were about to cause the public schools of that county to close. I remembered Cash's assertion that the Yankee had made the

RED CLAY READER 16

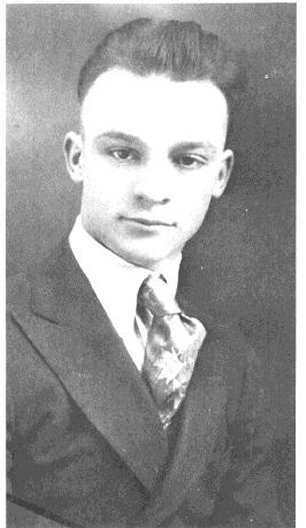

Wilbur J. Cash as a high school student at Shelby, N.

C.*

Wilbur J. Cash as a high school student at Shelby, N.

C.*

*[Site ed. nt.: Cash actually attended high school in Boiling Springs, ten miles from Shelby.]

new frontier in the South by destroying Southern institutions. I had thought it overstated but the men who stood about me on that thick, sweet Spring morning believed it. Cash had believed it. Nobody believed it more readily and less critically than my young friend in Psychology of Social Processes. Dimly, I began to understand the book at once on a simpler and more profound level.

The Mind of the South is about the South only as Faulkner's novels are about the South, because it belongs there. Its true locus is the human mind, with all of its brilliance and its sorrowing failure. W. J. Cash wrote about a state of mind he shared, sometimes consciously, sometimes surely unconsciously. His was a mind of the South, or of an educated man of the South, never more revealing than when self-revealing. The Harvard young were responding to these intensely personal signals as the disciples responded to Christ--to a fierce, sure, personal teaching. If they believed uncritically everything he had to say about the South, that was perhaps no less necessary than that the disciples believed in miracles; nor did it make what he had to say any less true.

The comparison with Faulkner seems to me to be especially apt. Cash wrote of Faulkner: "There is in his works a kind of fury of portraiture, a concentration on decadence and social horrors . . ." Cash, too, wrote with a fury of portraiture and he, too, "hated the South with the exasperated hate of a lover who cannot persuade the object of his affection to his desire."

He was given to extravagant fancies. He described how Charlotte, Winston, and Greensboro were building skyscrapers in 1914, having little more use for them "than a hog has for a morning coat." Then he observed: "Softly, do you not hear behind that the gallop of Jeb Stuart's cavalrymen? Do you not recognize it for the native gesture of an incurably romantic people, enamored before all else of the magnificent and spectacular . . . but I generalize too easily, I am a little fanciful."

His habit of exaggeration led him to be unfair at times. He disposed of the Yankee schoolmarm who came South in the Reconstruction floodtide as "horsefaced, bespectacled and spare of frame... no proper intellectual but at best a comic character, at worst a dangerous fool." Surely not just that; but the truth is there because Cash saw what the Southerner saw who suffered the Yankee schoolmarm's invasion of his land. Romantic, rhetorical, grandiloquent,disputations--that was Cash's Southerner and that was Cash, the writer, as well.

In style as well as substance Cash was part of what he conceived. At his best, describing how the Southern tinder of imagination had failed to ignite a literature because of the essential barrenness of the old way of life, he is the literary critic, viewing with an almost palpable pain the ruins of what might have been writing. "Imagination there was in plenty in this land with so much of the blood of the dreamy Celt and its warm sun, but it spent itself on puerilities, on cant and twisted logic, in rodomontade, and the feckless vaporings of sentimentality."

And Cash's language, even his simplest image, is undistilled Old South. "Black laughter," he wrote, "rolled in flood through Tar Heel legislative halls." What Yankee analyst--or for that matter what Southern analyst holding himself up

RED CLAY READER 17

to a mirror of objectivity--would have hazarded in describing a Reconstruction legislature the phrase "black laughter"? Is it just a metaphor, or is it a metaphor that only Cash could write seriously and that only a Southern Negro would understand as having absolutely no overtones of irony?

Read this way, Cash's book exerts an almost eerie power over the imagination. He was no fool, mistaking his own reflection in a mirror maze for a reality that did not exist. He saw all too clearly, but with the internal eye of the genius who sees through a glass flawed by the human experience he comprehends (and yet tells more than he comprehends). It is the agony of that telling reflected in Cash's deeply subjective style that lifts the book out of social criticism into literature. The Mind of the South is a great book today--a meaningful book to today's generation of readers--because it is really about the ultimate human condition, man's mind as life wore on it in a time and place which is the present as much as the past.

I was a little miffed that my young Yankee friends at

Harvard had seen this when I had not. So I gave them an equivocal

answer: The South was still Cash's South, I said, and then again

it was not. Cash would know why the South was saying never and he

would know that in the end The Progress would change the mind of

the South; but he could not know the kind of new Southerner all

this would produce. As an example, I cited a young man of my

acquaintance in Prince Edward County who was torn between his

loyalty to the old--the bad as well as the good of it--and his

keen sense of anticipation of the new. He was a prisoner in time,

trapped between the thrall of the past and the promise of the

future. Would Cash understand such a young man, I asked? Why not,

responded by friend in Psychology of Social Processes with the

mildest of smiles. Have you not just described--minus the

critical faculty--a man very much like Cash himself?

Site ed. note: When this article was published, James McBride Dabbs was a writer in Sumter, South Carolina who had taught college English in South Carolina between 1921 and 1942. He had contributed many articles and authored several books on the South, including This Is the South and Who Speaks for the South?

A Footnote on W. J. Cash and Southern Paradoxes

(Reprinted from the Red Clay Reader, Vol. 4, 1967)

"POOR CASH! He couldn't bear all the paradoxes he uncovered." That was the comment Alfred Knopf made to me during the publication of my book The Southern Heritage in 1958. Knopf had published Cash's The Mind of the South in 1941.

I don't know whether this explanation of the death of Cash is correct or not. But my experience tells me it may be. This is the experience I had while preparing for my later book Who Speaks for the South? The more I studied, the more aware I became of the paradoxes of Southern life. The more aware also that the Southerner who attempts to probe these paradoxes needs to be well balanced. If he harbors too many ambiguities, paradoxes, and contradictions within himself, he will find them written large in his culture and may be overwhelmed by them. As perhaps Cash had been. An outsider studying the South does not run this risk. The paradoxes he uncovers are his own only so far as he is human. His flaws are not immediately matched and deepened by the flaws of the culture.

Perhaps I should mention some of these Southern paradoxes. The existence side by side of kindness, even compassion, and cruelty; the swift change from agreeableness to violence, from indirection to terrible direction; the change from easy speech to menacing silence; the contrast between the flowing social life of the South and the deep inner privacy which may be privation and loneliness. "I think Southerners are the loneliest people in the world," a Southern woman once

RED CLAY READER 18

Cash and his publisher, Alfred A. Knopf (left), a short time after the 1941 publication of The Mind of the South.

(Site Publisher's note: More accurately, the above photograph was taken at the Hotel Charlotte, February 20, 1941, by a photographer for The Charlotte News. Knopf had come to Charlotte to celebrate the release of the book ten days earlier and to discuss Cash's planned proposal for an epochal novel about a cotton baron family in the twentieth century South, "nothing like the legend-mongers had made it out to be". When asked by News reporter, Pete McKnight, Cash's longtime friend, whether Cash could write a novel, Knopf responded, "It's not up to me to say whether Cash can or can not write a novel. It's up to Cash... And the best way for him to find out whether he can write novels or not is to try. If he can, swell. Nothing will be better news for us." From: W.J. Cash: A Life, Bruce Clayton, p. 169, citing Charlotte News, Feb. 21, 1941.)

remarked to me. We are a religious people, nominally Christian, who insist upon Christian doctrine and so often deny Christian practice. We speak the words of love, accept the fact of injustice, and are shot through with sentimentality.

These ambiguities, paradoxes, and contradictions have never really disturbed me. I see sufficient reason for their existence. I do not admire our unhappy, or evil, traits; but I do find human nature wonderful in its complexity. Though I wish that the South could strengthen its love with justice, I am not discouraged. After all, the universe itself is of doubtful quality. I have found it at moments patently unjust, at other moments hinting of a love beyond words. The worst, the best, you can say of the South is, we are human. This is troublesome in a machine-tooled world, but it is at least interesting. And there is the possibility that the universe is not machine-tooled.

RED CLAY READER 19

VOLUME 4, 1967