The American Mercury Years 1929-1935

Each of W.J. Cash's eight articles for The Mercury appears here, and includes at its heading graphics from the magazine and an introductory note. The first three articles "Jehovah of the Tar Heels", "The Mind of the South", and "The War in the South", were written in close proximity to one another, appearing in July, 1929, October, 1929, and February, 1930; and form essentially a related trilogy on Southern politics, culture, and the South's reaction to the labor movement and attempted unionization.

The remaining five articles, in order of publication are: "Paladin of the Drys", a sardonic critique of North Carolina Senator Cameron Morrison, published in October, 1931, "Close View of a Calvinist Lhasa", a biting look at Charlotte, published in April, 1933, "Buck Duke's University", an early examination of the institution of higher learning bearing his name, from the September, 1933 issue, "Holy Men Muff a Chance", a satiric prodding of Fundamentalism, appearing in January, 1934, and "Genesis of a Southern Cracker", May, 1935, a short concluding article on the truer than widely believed background of the average Southerner in which Cash began to develop a clearer thesis on Southern origins, a thesis to be amplified in the The Mind of the South, to be published six years hence.

These eight articles taken together form a fair palette for a sketch preliminary to the far more expansive portrait of the South in the subsequent book involving much the same topics.

The often-discussed "Menckenian style" attributed to Cash is certainly more evident in these eight articles than in The Mind of the South; yet, probably too much is made of this notion by analysts of Cash. Cash was 29 years old when he began writing for The Mercury and 35 when the last article appeared. In this time, he matured in his formulation of ideas and that increasing grasp of the subject matter is evident; that is not to say that the early articles are callow for they are fully formed, well thought out, and executed with an aplomb seldom seen in authors twice Cash's age at the time. As to style, however, clearly the articles display the pen of a more youthful Cash than does the book, possessed of more dry wit and more acerbic cynicism; by the same token, they feel freer than the book with the probable consequence to the reader of being more inspirational of action to ameliorate the problems examined. And, ultimately, the articles are more purely entertaining, though less substantive, than the book, precisely because of Cash's more evident bouncy, rhythmic style, almost subject to being set to meter and music at times, (as were whole sections of the book as well, but to a lesser extent).

This marks the first time that all

eight articles have ever been assembled together; the primary

basic subjects--racism, obscurantism, intolerance, and corrupt,

intellectually dishonest politics and politicians--always seem

with us and perhaps therefore do not properly belong to any one

decade or even century and certainly are not reserved to any

particular locality, state, or region of the country. It is the

hope of the site publisher that the articles provide insight not

only to Cash and those harsh Depression years of the Thirties in

which he lived and wrote, but, perhaps to these times as well,

both vis à vis the South and other parts of the country

suffering from time to time the same sorts of basic human pathos,

as well as human comedy, discussed.

A Brief Word on Words

In regard to the articles and their topics, inflammatory to this day, the following obligatory note must regrettably be made for our times: Cash wrote with irony and Jungian persona. If you are unfamiliar with these tools of the writer, usually reserved to novelists and poets, then please study the terms before reading Cash. Even if you are familiar with the concepts but have forgotten a little about the nuances of their meaning, do not be chagrined to look them up again; it is always worthwhile to taste sweeter plums each new spring.

Cash was always an aspiring novelist, read novels assiduously throughout his life, could name characters of novels and their roles years after the reading, and used these creative writing tools thus absorbed in order to survive by his wits--to enable him to say things in local and national print media which could not be said at that time by anyone from within the South without being tarred and feathered and run out of the region or lynched--as Cash, himself, pointed out repeatedly in The Mind of the South.

He hoped to diffuse some of this violent tension through the use of the very terms which the racists and lynchers and their political enablers used, in order to mirror their words and actions and shame them in writing or, more to the point, enable the more educated, peaceful people of the community to have a vehicle through which to fight back with intelligence and understanding and less risk of social or economic ostracism or worse.

The use of the terms in question is not to mock the subject of the terms, in most cases, and is obviously not to lend credence to any stereotype; the terms instead appear to be used as paradoxical conundrums into which it seems Cash hoped to box the thoughts of the very people who used such virulent terms to hurt others. Words, in other words, as mirrors, to defeat and discharge the use of such terms and, more importantly, the ideas, beliefs, and actions which stimulated and tacitly permitted their use; not to inflame, as other writers had routinely employed them for centuries in the South, culminating in the racist novels of Thomas Dixon. More recent examples of this type of literary usage of such terms can be found in the writing of James Baldwin, some of the songs of Josh White or of Bob Dylan, and the humor of Lenny Bruce, Monty Python or Richard Preyer. Even more recently, one can hear the strains of persona and irony in the songs of Randy Newman, Leonard Cohen, John Lennon, and contemporaneously, Jewel, U-2, or any number of "indies" and rap artists.

Thus, as you read, you will encounter phraseology adopted by Cash which today is not in use by respectable editorialists and journalists: "white trash", "lint-heads" (referring to cotton-mill workers, among whom Cash counted himself from his summer spent working in the cotton-mill owned by his uncle), "nigger", Nigger", "niggerphobia", "niggerwool", "wop", "coon", "Cuffy", referring to an exemplar for the politically manipulated African-American, "Hun university", "Yankee", "bumpkin", "hill-billy", "mill-billy", and other such labels and phrases referring to various institutions and groups of people, black, white, and colors in between. But no one need be offended or even raise an eyebrow regarding these blushingly retrograde sounding words and phrases, seemingly, to our more modern, sensitive ears, antithetical to Cash's broad spirit demanding equitable treatment for everyone. When Cash was being entirely serious, he used "black" and "Negro", "white" and "Northern" and other such neutral phrases; in fact, in 1929, it was indeed not the expected norm for any Southern white writer to employ the use of the word "Negro" and capitalize it as Cash did (much less in the context of condemning lynching and the Klan). He did not expect thanks for that; he simply believed it was proper justice as well as English.

Cash took on in his editorials and book some of the most powerful and violently determined political forces the country has ever known--in the South of his time and in the memories which lingered in others of his time of their storied forebears. He labelled anyone of them given to intolerance or race-baiting as "Neanderthalers", or worse. And, it is plain in context that, in those instances, his terms were in no way used in ironic fashion. (If you doubt me, use the convenience of your "Find" menu, plug in some of these words, and scroll down this page and through the subsequent Mercury articles, reading the paragraph or two of context for each such usage; it should become obvious what Cash was doing.)

Most writers on Cash, including in the preface to the 1991 reprint of The Mind of the South, have pointed out the fact that in the Twenties and Thirties, such language was in common usage in liberal, progressive editorial writing throughout the country, including by Cash's renowned mentor, H.L. Mencken. Yet, no one need offer an apologia for Cash and his words. He used his vocabulary--educated and vernacular--powerfully and pointedly.

Nevertheless, as obvious as this point may seem, some misunderstand. One professor of history at a prominent university has actually suggested as recently as 1991 that Cash was a racist, even comparing him to his nemesis, Dixon, and even going so far as to provide in print an elaborately framed concatenation of semantic arguments to "prove" the thesis. (Whether this particular commentary was made for the sake of stimulating controversy and critique at a seminar on Cash, where it initially occurred, or was seriously propounded as truth in a wedded premise, the notion devolves to the preposterous: Cash despised intolerance of any sort and dedicated his entire adult writing life to its eradication; he despised Dixon's writing with a passion and openly excoriated him and the Ku Klux Klan as early as 1929 in the opening paragraphs of "The Mind of the South" piece for the Mercury. And as Dixon was from Shelby, N.C., just ten miles up the road from Cash's residence at the time, and as the woods were very much still full of racists and lynchers who revered the Reverend Dixon for spreading their corrupt thinking far and wide, such open mocking of these forces may well have eventually cost Cash his life. Indeed, such reverence of Dixon apparently still persists around Shelby that as lately as 1995, The Charlotte Observer found Dixon's memory long installed in the "Cleveland County Hall of Fame" at the Shelby courthouse while W.J. Cash still remained on the outside--even though he wrote much of The Mind of the South in Shelby. Cash's close family, incidentally, has long considered it a blight that in 1946, Dixon's remains were parked under a gaudy obelisk full of his "accomplishments" and roles, not 50 yards from Cash's burial place in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby. (The simple flat 18-inch square head-marker on Cash's grave bears his father's chosen words: "Behind the dim unknown standeth God within the shadow keeping watch above his own"; the line preceding it in the poem from which this line comes--"The Present Crisis", written by James Russell Lowell on the occasion of Lincoln's assassination--is: "Truth forever on the scaffold, Wrong forever on the throne/ Yet that scaffold sways the future, and...")

Cash might have laughed, of course, at all of this continued periodic controversy surrounding his views on the South and its cultural mind, including the silliness of the professor, long removed to the North, who called him a racist 50 years after his death; for Cash understood that life is full of irony and that is the color of life. (To be fair, this same professor, it should be noted, perhaps has had a change of mind: speaking in 1998 at a commencement in upstate New York, the professor stated as sage advice to the students that if they could not say anything good about a person, they should say nothing at all. Maybe the good professor has thus profited from that advice since the 1991 expression of an exclusively negative opinion on W.J. Cash.)

Cash was probably the first Southern journalist since the Civil War to appear in the national press openly criticising lynching; he even took on law enforcement in North Carolina who he accused of standing by idly to allow the lynching of blacks and labor organizers and any sympathizer to these causes. So vital and unique were his remarks on lynching that the N.A.A.C.P., at a time when Thurgood Marshall was its special counsel, openly and expressly thanked him in 1941 for his book and its strong stand against lynching.

Yet, to some modern ears, the language is the issue; the semantics, the important matter--not the substance of what is expressed, nor the context in which the words appear in the whole, nor the art necessary to employ to be able to safely say it at a particularly volatile time in history. Times have changed since the Sixties and earlier: it takes no great courage today for someone to write publicly that vigilante lynching is wrong, that racism or ethnicism is wrong, that invidious stereotypes of any kind are wrong, that use of racial epithets is wrong--that everyone has equal rights and opportunity under the law in any decent societal system of mores. It is always worth the reminder: such voicing of these high-minded beliefs should never be treated as truistic or shop-worn from their repetition or greeted with, "I know that", and a roll of the eyes--even today; yet, these are widely accepted truths now and their expression does not generally incur the risk of the rope, even in the deepest rural areas of the still sometimes wrathful South. In 1929, however, one literally risked his or her life--or at least livelihood--to dare to stand on a Southern soapbox, especially one placed in a small rural milltown, and say such things amid avowed and stamped racists and lynchers. Murderers murder people--or destroy their reputations--to keep their worst crimes--or that of their fathers and grandfathers--from being discovered. Cash knew this chilling fact; understood the perverse psychology; had seen it up close among his very neighbors in Gaffney, Boiling Springs and Shelby.

Whether Cash's death at the ne plus ultra of his powers at age 41, just as he had a chance to place his ideas into an entertainment format--a novel--and thereby make his great debate between Reason and the Race-baiter more accessible to more people, was the result of the long-promulgated suicide or outright murder by Nazis and/or the Ku Klux Klan or by sympathizers of either or both groups, it should be kept uppermost in mind that the views he propounded, accepted today, but resisted with passion and violence in those times and for decades later, likely directly led to his premature death.

It is therefore important to be cognizant of the context of these articles and the book through time, and the risk being taken in them, so that severe, blinding misunderstanding does not result, stultifying truth in the end.

Through the years, most students of Cash have understood the accurate picture in this regard, sub silentio or expressly; but the art of reading and understanding high-minded literature has unfortunately gradually diminished in our times, with the stress on movies and television and more literal-minded interpretations of subject-matter, a process of devolution begun in Cash's time, (see Cash's commentary on the topic in "Holy Men Muff a Chance"), and heavily influenced in fact by the Reverend Thomas Dixon and his quite literal trash novels. The resulting movie, "Birth of a Nation", was actually viewed and endorsed, racism and all, "Aryan brotherhood--north and south--reunited against the negro party" phraseology and all, in 1915 by Woodrow Wilson, and in joint session in the halls of the Capitol, by both houses of Congress, and by the United States Supreme Court. And, sadly, from that publicity and endorsement given this first epic length film, the rest of Hollywood history owes much to this founding father of the medium, "actor, lawyer, minister, writer" Thomas Dixon of Shelby, North Carolina. It is a thought, perhaps, worth keeping when revering the unadorned minimalist expression of ideas over symbolic, poetic rendering or in relying too much or exclusively on films and television to teach history.

Yet, it is also true that in our more information-laden times, there is, most of the time, less critical need for the cloaked meaning and the symbolic understanding than was necessary by the more educated members of society 40 years ago and more. Such conditions as we enjoy today, however, notwithstanding, it is important to grip that things have not always been the case and may not always be the case in the future. It is thus important at least to appreciate such literary usage of language and its power to change the opinions ultimately of the most acrid and tenaciously dark aspects of the human mind, lest we have no choice except to employ such irony and symbolic use of language on some future day to combat again some more goose-steppers somewhere in our midst.

It is wise to avoid, therefore, being led astray by a complete misunderstanding of the intended context of individual words or inartful displays of "analysis" performed without any apparent awareness of the beneficial art being practiced and its context. Words are short-hand symbols for meaning and the meaning appears not always just in the dictionary, but also within the nuances intended by the author provided in the context in which the words appear; and not just in the context of the sentence containing the words, but the paragraph, and the whole text by the particular author. (While this seems obvious enough, many seem to miss the point today too much; so pardon the pointing lesson.) Writing must always be viewed in that fashion or we ultimately fashion a form of speech that is so devoid of intuitive, creative input that the search for truth in its purest form--with the ability stripped away of language to really affect beliefs and actions--is potentially pretermitted; and language is alienated from any useful meaning whatsoever. That, it seems, would be the worst lesson of all to impart to those who follow us. Tender ears will always hear words of all stripes from a very tender age; I did--as a youth in the Fifties and Sixties--and long before I ever heard them at the movies or read them in any book. The question becomes therefore how do we teach the reading, the listening, the usage of the words, immediately offensive or not? Should it be for the sake of increased courtliness in parlance? Or should the lesson be to employ words--ugly and pretty--to search for the most precious thing there is--ever elusive truth?

It is not overly dramatic to state again that this is the reason our Constitution's Bill of Rights begins with the right of freedom of speech; the founders had witnessed the evils of its stifling by the royal-hearted among them too often and were willing to risk their lives to establish this most precious right anyone has. W.J. Cash saw the strutting royal stiflers--the "bluecoats" and "parvenus", as he called them--among the rural peacocks of piedmont North and South Carolina and he wrote of them ruefully--and with good reason. He had to survive among them.

It is ultimately the hope that these articles provide a small part of truth, and, more importantly, how to get at it and make it available and safe for others to see. With that result, no one will be able to say that we can not see.

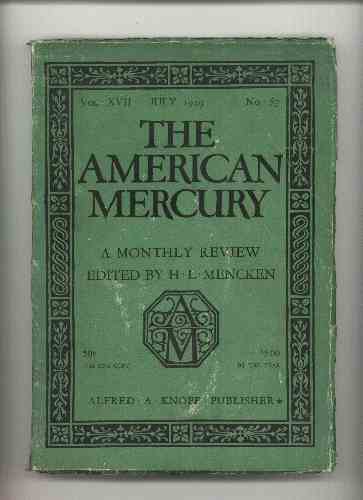

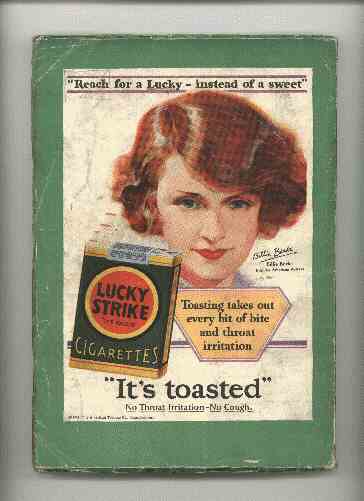

Front and back of original July, 1929 American Mercury in which appeared W.J. Cash's first article scalding North Carolina Senator Furnifold Simmons, "Jehovah of the Tar Heels"

Jehovah of the Tar Heels

Site Publisher's Note: While a nearly seventy year old article on North Carolina politics may seem at first arcane and of little relevance to present day politics anywhere, read on and decide for yourself whether the article belongs among the cobwebs of the library shelves. What Cash saw and foresaw in 1929 did not come to full fruition in North Carolina until 1980, but it did finally occur. The legacy of North Carolina senators like Furnifold Simmons can be traced to their latter day counterparts quite easily. Present day Senator Jesse Helms obtained his start in politics as campaign manager for race-baiting Democratic senatorial candidate Willis Smith who in 1950 defeated populist liberal University of North Carolina president Frank Porter Graham, who Cash admired greatly. Smith's campaign won largely through the very tactics Cash lampoons with a jaundiced and quite serious eye in the article which follows. It is evident from the tone of this opening article for The Mercury that Cash was an angry young man, barely able to restrain his open contempt for the system of hypocritical, racist, zenophobic, and ethno-centrist money-sopped politics strangling off rationality in his beloved native state. North Carolina remained a one-party state through the 1960's and many such adherents to the old politics followed in the footsteps of Simmons as only nominal Democrats before finally bolting to the full-fledged ranks of the inaptly dubbed "conservative", evangelical-soaked, right wing of the Republican Party; such was of course true throughout the South until at least the early 1970's. As you read, close your eyes, forget that Cash wrote in 1929, and see how much startlingly remains true today.

Go Back to Top of Page Go Home

JEHOVAH OF THE TAR HEELS

BY W. J. CASH

A BOUT the Hon. Furnifold McLendel Simmons, LL.D., senior United States Senator from North Carolina, there is nothing reminiscent of either God or the traditional Southern Senator. Yet for thirty years he has successfully played God in his native province, and he has retained his seat in the Senate longer than any party colleague now sitting in that one-time august body.

In him one discovers nothing of the flashing eye, the craggy mien, the Bryanesque shine which one instinctively associates with the Lord God Jehovah and the Senator from the South. Nevertheless, the man's deeds, in the aggregate, are worthy of the stateliest Neanderthaler who ever cooled his heels on a Capitol Hill desk, worthy even of Jehovah in His most waggish moments, as reported by the Hebrew historians. Indeed, I gravely doubt that in all the gallery of illustrious rogues who have graced the Senate in the past, nor even ill Omnipotence Itself, could one find a talent capable of measuring up to what begins to emerge as Simmons' salient achievement. Only a Gargantua, it seems to me, could ever have risen to that gigantic yardstick. It is a sad commentary on something--what, I don't know--that the man himself is humorless, and hence without power to savor the Rabelaisian quality of his handiwork. For all that, the fact remains that his chef-d' oeuvre is of a piece with the immortal buffoon's filching of the bells of Our Lady of Paris to make a necklace for his mare.

The record of Simmons' career makes one of the saltiest chapters in the history of American politics; it is a devastating expose of the essential sottishness of democracy. For the plain and horrible fact is that he is a Republican, and has always been Republican by every rational test. For thirty years, sitting as a Democrat, he has served Republican causes and the Republican lamas--with all the power that has been his in the Senate and in North Carolina--with all the very power that he arrived at and has maintained by captaining the Democratic party in his State, by making himself the hero and veritable God of Hosts of its Democrats, to be worshipped blindly and drunkenly, and obeyed without question. And in Democratic livery, with the dazed butts of his genius gaping on, he has now slain the revolt which at last raised its head by lopping 50,000 from the Democratic host to create what amounts to a third party, and has intrenched himself a well-nigh impregnable position by reducing the remaining Democrats to a choice between his mastery or that of Republicans. Thereby, quite incidentally but inevitably, he has brought about what no avowed Republican has ever been able to bring about: he has lifted the Republican party in the State to fighting equality with its foe, and set North Carolina on a path that, according to every omen, must lead finally to Republican rule. That is the Simmons masterpiece.

So long ago as 1912, it was clear to his contemporaries in the

Senate, and to all the nation with the exception of his

infatuated, nigger-haunted constituency, that he was a Republican.

The Democrats were then at the height of the Progressive

Liberalism which was to end with the War for Humanity. The

Republicans, taking the

JEHOVAH OF THE TAR HEELS 311

other direction, had kicked the smelly liberalism of Roosevelt downstairs and embarked on the reaction which was to flower in the Ohio Gang. It was a time of charming forthrightness. Sweetness and light had not yet been hatched. Collier's, under the editorship of Norman Hapgood, thundered against the Interests. The People were the Masses. The flaming rapier of their righteousness was, in theory, the Democratic party. The money-kings were, ipso facto, the money-hogs, the enemies of the People, to be put down with fire and sword. Their bodyguard was the Republican party. The battle-line, dividing the sheep from the damned, was drawn clearly and precisely on the tariff.

In 1908 the Democratic platform declared for the free entry of lumber. Simmons, a year later, repudiated that position on the Senate floor by defending the prohibitive duty imposed by the Payne-Aldrich bill and by voting for it on roll-call. He defended his action on the ground that he was serving the interests of his own State. But the lumber interests of North Carolina, at that time, consisted only of half a dozen large companies. The total number of people even remotely interested in the trade was not 15% of the population. Moreover, the Democratic campaign had been conducted in the western section of the State with particular emphasis on the assurance of cheap lumber. But Simmons voted for the Payne-Aldrich lumber schedule--and against the expulsion of William Lorimer, the Stone Age predecessor of Bill Vare and Frank Smith, whose election was charged to bribery of the Illinois legislature by the lumber interests.

When Aldrich increased the duty on coal 60% and set the barons gurgling hosannas, Simmons dutifully voted with him, after first voting against a proposed reduction of 40%. He prayed protection for the beleaguered cotton-seed oil manufacturers. He championed the downtrodden American pineapple. He spoke and voted for higher duties on building materials (other than lumber) and carpenter's tools. And he voted for Aldrich's enormously increased duty on iron ore, darling of the Steel Trust. Mark Sullivan, in Collier's for September 28, 1912, illuminated his votes with brutal directness:

Not only did Simmons vote for a high tariff on lumber, he addressed the Senate in favor of it: "I am ready, with him and with any other man on either side of the chamber, to extend the same treatment to every product embraced in this bill; I do not care in what section of the country it is located." There you have it. That is exactly how every high tariff bill has been passed--"'You vote for my lumber, I'll vote for your steel.'' Senator Simmons has put into a single sentence the whole philosophy and mechanism of logrolling.

A little earlier, Gilson Gardner was writing:

Senator Penrose is following the footsteps of his predecessor, Mr. Aldrich, in trading across the party line when it comes to protecting the high tariff schedules. The other day, when the Pennsylvania Senator reported his suggested revision of the wool schedule, he held a little informal meeting in the Senate lobby with Senator Simmons of North Carolina. The writer stood by and heard this conversation:

SIMMONS--What do you want us to do? Do you need any votes?

PENROSE--No. I think I can put it over; you fellows vote for your own bill.

SIMMONS--You don't need any of our votes then ?

PENROSE--No. ... I'll take a chance on putting it over and then I'll fix it up in conference.

Throughout this period, the pet hate of the Democrats was the ocean mail subsidy. To them it showed the hand of Big Business in the public till. Contrariwise, in the late years of the Taft reign, the proposed tariff reciprocity agreement with Canada, sanctified as it was by Democratic tradition from Jackson onward, became their pet passion. Simmons twice addressed the Senate and voted in behalf of mail subsidy bills, and he was one of three Democratic Senators voting against reciprocity. He came to the end of the extra session of 1911 with a record of having sided with the Republicans in nineteen of a total of forty-three votes.

In 1912, he found his seat contested by Governor W. W. Kitchin,

shaggy, eloquent, fire-eating, as reminiscent of the traditional

Southern Senator as Simmons is not. Revolt menaced, with Kitchin

and

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 312

his campaign manager, Frank McNinch--who was afterward to glorify God as chairman of the State Anti-Smith Committee--ringing the changes on the charge that Simmons was a Republican. McNinch is a praying, grandiloquent fellow from the godly town of Charlotte, much given to such Scriptural injunctions as ''To your tents, O Israel!'' and passionately addicted to Great Moral Ideas. He daily occupied pages in the State newspapers with advertisements of the Simmons record on tariff, mail subsidy, and reciprocity.

The Democratic party of the whole nation was demanding Simmons' scalp. Mark Sullivan, writing in Collier's on September 28, 1912, cited the activities of Gorman and Brice, Democrats, against the Wilson tariff bill of 1894, quoted Cleveland's famous phrase, ''the deadly blight of treason,'' and proceeded to lay on with the knout:

Once more . . . the Democratic party is approaching another ''hour of might." . . . Again in its hour of triumph the party is going to be threatened by the blight of treason. Again it is going to find its Gorman and its Brice. The Gorman of the coming year will be Simmons of North Carolina--unless the people of North Carolina vote to keep him at home.

Said Bryan, in his Commoner, October 11, 1912:

Senator Simmons asks the people of North Carolina for reelection. He ought to be defeated.... He would do very well as a representative of the standpat Republican party.

The Helena (Montana) Independent minced no words:

Simmons is the same kind of Democrat that Aldrich, Penrose, Crane and Smoot are Republicans--a rank Protectionist--in league with the Interests, against the people, and ever willing to trade anything and everything in the Senate to gratify the greed of the grafters.

Harper's Weekly, the Baltimore Sun, the New York World, the Indianapolis News, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, the New Orleans States, the Dallas News, the Chattanooga News, the Columbia State, and scores of other Democratic organs joined the chorus. But Simmons won--and his victory was dramatic evidence of the unshakable worship of his constituency. That worship has always mystified outsiders. There is, I repeat, nothing in Simmons reminiscent of the traditional Southern Senator, nothing of the leonine and sweating statesman torture-marked by Service, nothing of the vaudeville talent that delights the yokel. Eloquence? Three-fourths of his audience walked out on him when he spoke at Raleigh last November on the eve of election. Yet that same audience had cheered him madly when he appeared on the platform. Personal charm? He might be any bookkeeper, any village banker or sexton. He is totally undistinguished in appearance save for an almost oriental slant to his eyes, save for the petulant downward curve at the corners of his mouth. One gains an impression of a small boy about to cry. Perhaps that is the ultimate secret of his strength--infantilism, the immeasurable, implacable wanting of a child. If so, it is an infantilism supported by an extraordinarily shrewd mind.

II

His is the story of a realist, moved only by self-interest, knowing exactly what he wants, and playing upon zanies and romantics to attain his ends. His deeds are those of a scientist who has measured exactly the potentialities in the ferment of hate and fear in the minds of cowherds and cotton-mill peons on the one hand, and the bitter nostalgia for lost glories in the master class of the ancien regime on the other. His method has been the time-honored one of using the red herring. The tools with which he has attained and held his godhood have been the Nigger and the Cotton Mill. Lately, however, he has replaced the Nigger with Great Moral Ideas.

It is necessary to understand that he came upon the stage in a

period of transition. Reconstruction, the Nigger in Politics, was

flaring for the last time. The Cleveland panic had swept the

Farmers' Alliance from the Democratic party into the Populist

camp, from which it had slipped swiftly into the Republican fold

JEHOVAH OF THE TAR HEELS 313

through the process of Fusion. A Republican governor, backed by a Republican Assembly, to make certain the Republican hold on the State, began the systematic enrollment of Negro voters, rained honors upon them, being particularly lavish in the creation of black magistrates. Indignation swept the State. Violence broke out. At Wilmington, a Negro editor, having cast aspersions on the virtue of the white female, was ordered to leave town; when he declined, a mob destroyed his printing plant. Rioting followed, with the net result that many blacks--the number is curiously indefinite--were killed and thrown into the Cape Fear river.

In that red hour Simmons, who had already shown his capacity as a local machine-boss, was made chairman of the State Democratic executive Committee. A Democratic convention, dominated by him, adopted a White Supremacy platform. On the heels of it, Red Shirt Clubs, modelled on the Ku Klux Klan of thirty years before but differing from that organization in the absence of masks, night forays and violence, sprang up overnight to deflate the new-found glory of the black brother with ominous parades. On election day the coon shivered at home behind closed shutters and the Democrats swept back to power.

It was in fact the end of the blackamoor as a menace to the ascendancy of the Goth. The Republican party, convinced of the utility of attempting to rise on the shoulders of the Ethiop, was to turn its back on him and spend the next thirty years, in sackcloth and ashes, at the bitter task of rehabilitating itself in the esteem of the outraged Nordics. But Simmons had emerged as the hero of the conflict; in the popular mind, he was the Little Giant of New Bern who, single-handed, had slain the dragon of Nigger Rule. In point of fact, it was the life-long contention of Claude Kitchin, leader of the House Democrats under Wilson, that he himself drew the White Supremacy platform. And former Governor Cameron Morrison claimed in the Smith campaign that it was he who spawned the Red Shirt scheme. That is as it may be. What matters here is that Simmons got all the glory, and used it to elbow aside more gaudy fellows and snatch the Senatorial toga. Once in power, he found the Nigger a weapon ready to his hand to keep him there.

III

He had grown up in the old river town of New Bern against the background of Reconstruction, and understood the morbid concern of his people with the menace of the black. Old bogeys live long in conservative communities; ghosts sway alike the merely ignorant and the backward-yearning romantic--the two classes which embrace the mass of North Carolinians. The shadow of the blackamoor was to be as haunting in the next thirty years as the blue-gummed fact of him had been in the previous thirty. Accordingly, Simmons made the Nigger his major theme. For thirty years, mounted on the Democratic ass, he rode forth, in fanfare of trumpets, to ghostly jousts which cheering thousands counted real.

The medium through which he fed the flame of this niggerphobia was the so-called Simmons machine, which reached to the headwaters of every Little Buffalo and Sandy Run in North Carolina, into every alley of every Factorytown. It carefully planted as axiomatic in the people's mind the belief that its overthrow meant inevitable subjection to their ax-lackeys. L'e'tat c'est moi was the Simmons dictum; he was the symbol of White Supremacy; topple him, it toppled. ''The Senator thinks " became the rule of conduct for every loyal Democrat.

But if the machine made possible the feeding of his

constituency's niggerphobia and the consequent consolidation of

his power, his very identification with the White Supremacy

mummery made possible, in turn, the elaboration and perfection of

the machine. Power was used to advance power. Every Democratic

politician came

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 314

to be embraced within the machine; any attempt to operate outside it began to be political suicide. It named Governors, passed on all appointments, framed all legislative programmes; Simmons was merciless in destroying those who opposed him; to those who served him well he gave commensurate rewards. Impatient souls sometimes rebelled, but only to rue their madness. Kitchin and McNinch tried it in 1912; it ended Kitchin's career and McNinch required fifteen years to crawl back.

The old boy's diversion of attention from his record has been manfully aided by the newspapers of the State. The most powerful of these is the hymn-singing Charlotte Observer. Behind them lies the Southern Power Company. This huge corporation, darling of the late Buck Duke, once a blood-brother to Blackbeard but now canonized in North Carolina, along with Dr. Wilson and Walter Hines Page of the Bended Knee, is generally credited with being the power behind all Simmons' activities. Certainly, his record of smoothing the political pathway for its grabbing of water-power sites in North Carolina, of consistent voting with the Power Lobby in the Senate, and of opposition to the Power Trust inquiry indicates a close alliance, at least. The advertising club of the company keeps the newspapers quiet.

Ergo, Simmons' deeds have never been reported in the State; correspondents sent to Washington, dull pates for the most part, have exuded only adoration for the Presence; if a humorous oaf risked blasphemy, he was fired. McNinch, it is true, advertised the record in 1912, but he confined his efforts to the larger dailies, unread in the rural districts; the bucolic gazettes wisely preferred to copy editorials from the same dailies which pictured the Senator as the bleeding Christ of the farmers, and so the attacks were quickly forgotten as campaign thunder.

Ironically enough, as the Republicans passed out in sorrow, the stage was being set for a drama which was to sweep the State steadily Republican-ward. Cottonmills were rising upon the land; North Carolina was at the beginning of the era which was to lift her from turpentine and razorbacks to the forerank of Kiwanis. The gentry were losing their ascendancy to coarser, more virile spirits; the Cannons, Reynoldses, and Dukes were emerging as the new masters of a new order. With them, Simmons, with canny judgment, promptly aligned himself; and in that alliance is probably to be found the explanation of his interior Republicanism. For these hairy fellows, who eventually were to give tone to the whole life of the State, were, naturally enough, Republican in their philosophy and yearnings, though for many years they were to find it imperative to hide that fact under a bland Democratic front. They wanted tariff protection--and Simmons saw that they got it. And so, in nigger-haunted North Carolina, the bumpkin and the clod began to complain to God about the rising cost of houses, wool clothing, ploughs, coal and food, and meanwhile the Senator explained to the Senate that his tariff activities were actuated by a passion to bolster the wages of the cotton-mill serfs! The cynical regard in which his colleagues hold his nominal Democracy was patent in the organization of the last Senate when, despite his clear title to the post, they declined to make him minority leader, choosing Joe Robinson instead.

But if he was clearly a Republican by 1912, that is not to say

that he nursed dreams of lifting the party to power in North

Carolina and of himself going over to it. No sword-eating Colonel

of the old South, suh, ever breathed more sulphurous hate for

Damned Radicals than he did in his public bulls. For thirty years,

under his leadership, Republicans were nobodies who emerged from

nowhere on election day to cast apologetic votes and fade swiftly

into nowhere again; Republicans were the ax-barkeeps who tended

postoffices; Republicans were brass-armored come-ons who had

bartered their souls for

JEHOVAH OF THE TAR HEELS 315

"a handful of silver . . . a riband." It was more than politics; it involved social standing. Hell was a condition in which one associated, perforce, with Republicans; so one propitiated Jehovah--and Simmons. The Democratic ticket from constable to President; that was the Simmons law. One defied it at peril; one lost caste; one was suspected of consorting with niggers; one was even likely to find one's banker regretful but firm. The decline of more than one solid bourgeois family to the cotton-mills can be traced to a flouting of it.

For years, the Republicans of the State took the old boy at his word, and repaid his hate with interest, but then word of his knightly conduct on distant fields gradually seeped in to give them pause, and by 1912 thousands of them were expressing their admiration by voting for him in Democratic primaries--indeed, Governor Kitchin charged that Simmons was nominated over him purely through their vote--, confident, I suspect, that they read on the Senator's face a ribald wink--that was not there.

I say it was not there; of that, of course, I cannot be sure. But he sprang from slave-owning stock and so was born to the Democratic party; he accepted his destiny, moulded it to his personality, and was, I think, thoroughly loyal in the sense of being willing to destroy the enemy, even though that enemy was fashioned in his own image. His genius is purely objective; self-analysis is no part of him. He would, I suppose, resent angrily the suggestion that he is Republican in all but name.

They were probably bitter and honest tears he wept in the Senate last Fall when he charged that foes at home were seeking to destroy him. They were. Ergo, it is highly likely that the lifting up of the Republican party necessarily involved in his activities in the 1928 campaign was merely incidental to his hard choice between loyalty and self-protection.

For, from 1920 to 1928, the Simmons power had been decaying. Max Gardner, the present Governor, had been quietly building up a rival machine. In 1920 he had almost snatched the gubernatorial nomination from the Simmons candidate, Cameron Morrison; and, so powerful was his following that the machine found it prudent to come to a tacit agreement with him, whereby, if he would stump the State for Morrison in the campaign against the Republicans, he might have the nomination unopposed in 1928. That was a confession of weakness; no other rebel had ever brought the machine to terms. Gardner had the backing of the strong Webb-Hoey clique, which has dominated Democratic politics in the Ninth Congressional District for twenty-five years. Moreover, he was young, magnetic, and eloquent. Simmons was old, past seventy; it was whispered in the State that he was in his dotage, and had become a mere tool in the hands of his ambitious secretary, Frank Hampton. The machine itself was disintegrating.

Gardner himself probably hopes to go to the Senate at some not too distant date. In the meantime, he would like to send his connection, Clyde R. Hoey, a former Congressman, to Washington to succeed Senator Overman, who is scheduled to retire at the end of his present term. Cameron Morrison also aspires to that seat. In the eastern section--rigid custom assigns a Senator each to the east and west--divers hopefuls, prior to 1928, had been loudly assuming that Simmons would retire in 1931, and leave the way clear for their ambitions. All these gentry, east and west, had shown a lamentable tendency to take matters into their own hands. That was distressing, more particularly since Frank McNinch, whose humble services had so far atoned for past derelictions that he had won a place close to the Senator's heart, also aspired, somewhat secretly, to the Simmons toga, and since Hampton, trained for years, had been anointed as the Senator's chosen successor.

That was the situation when Al Smith loomed over the skyline

and the pastors began to whet their bowie-knives.

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 316

IV

Early in 1928, Rodney Dutcher, a Washington correspondent, published a story to the effect that it was rumored in the capital that Simmons was presently to emerge as captain of the Smith forces in the South. The Senator replied merely that he was not the father of the rumor. In North Carolina it was whispered that he was angling for the vice-presidential place on the ticket with Al, a prize which was to go to his old enemy, Joe Robinson. It may have been. At any rate, when, about that time, Frank McNinch, at Charlotte, began to fulminate against Al and the Pope's ring, he was ignominiously muzzled.

But, whatever the truth of all this, Simmons, by mid-Summer, had made up his mind to take the bull by the horns, for before the apparition of Smith his Democratic enemies at home were hiding their heads in the sand and ardently saying nothing. Very well, he would end that. And so, to the whooping ecstasy of the political parsons, he announced that Al was ineligible, since his candidacy would inevitably raise Great Moral Issues, that he could never achieve the nomination, and that he (Simmons himself) would lead the righteous at Armageddon. That last promise he did not keep, for by the time the convention opened, it was clear that Smith was master, so Simmons contented himself with sulking at his home in New Bern.

Nevertheless, he had achieved his main purpose; his pronouncement against Al had maneuvered his foes from under cover, since they could no longer pretend ignorance concerning the designs of the Pope, and forced them, in order to appease the clamorings of the holy men, into joining him in opposing Smith's nomination on the ground of Great Moral Issues. Moreover, a tour de force, in which fleets of cruising automobiles swamped the precinct primaries, with Anti-Smith voters to win him control of the State's delegation to Houston, had given him the inestimable psychological advantage of apparently establishing that the people of North Carolina were overwhelmingly opposed to Smith--a proposition open to grave doubt, as a matter of fact, since a poll taken by the pious Charlotte Observer a month before had shown Smith a two-to-one favorite and since the parsons themselves had only dreamed of capturing a half of the delegation.

Now, just as his enemies, returning from Houston, were unlimbering their preliminary ballyhoo for Candidate Al, he struck again, this time below the belt. It was the thing they had told themselves ten thousand times could never happen. Was it not Simmons who had taught them to lisp ''from constable to President''? Perish the thought! The Senator would never desert! But he did desert, announcing simply that, though he would support the State ticket, he would not vote for Smith.

It was a master-stroke. Far from bringing down on his head the odium which is the portion of the turncoat, it definitely established him in the North Carolina mythology as a Man of Honor who placed Principle above Party, identified him forever with the rising philosophy of Great Moral Ideas, and increased his stature from that of a mere hero to that of a legendary figure, a tribal god. More, it just as definitely established his foes within the Democratic party as a snide lot of time-servers and bench-warmers, placing Party above Principle, opposing Great Moral Ideas, and, potentially if not actually in the hire of the Pope and the Rum Ring, which everybody below the Potomac knows to be one and the same.

The upshot was a majority in North Carolina for Dr. Hoover of 60,ooo votes. The Democratic majority is ordinarily 80,000.

One may not say that the State would not have gone Republican

in any case; that is a matter for dispute; religious hate is an

imponderable. Certainly, however, if it had gone Republican with

Simmons supporting Smith, it would have done so by a narrow

JEHOVAH OF THE TAR HEELS 317

margin. Moreover, and this is more significant, that margin would have represented an unorganized rabble, definitely on the defensive and eager enough to be swallowed up by the Democratic party again. What Simmons did was to clearly establish the ascendancy of Great Moral Ideas over party ties, demolish the ghost of the Nigger, inspire timid parsons with a lust for blood, and lend courage to faint-hearted voters by his example. His greatest achievement was to supply leadership, to weld the rabble into a compact, cohesive body, no longer on the defensive, no longer apologetic, but swaggering and shouting its moral superiority--to create a party, that is.

To be sure, in doing that he relinquished control of the regular Democratic party to his foes, but it was a party reduced to a size with its ancient antagonist, the Republican party. Today they face each other in the State, these two, the Republicans and the Democrats, the Republicans greasy-mouthed, shining-eyed, the Democrats gaunt, distinctly unhappy. Between them stand the 50,000--a minimum figure--of the pure in heart, the so-called Hoover-Democrats. The name is a misnomer; actually they are neither Democrats nor Republicans, and Dr. Hoover has less than nothing to do with them. Simply, they are Simmons men, shock troops of the Lord, whose Bayard the Senator is. At his command, they will vote en bloc either the Democratic or Republican ticket. The Senator's foes dreamed of war with him--they got it, with a vengeance. They sought mastery of the Democratic party; they have it. His is the balance of power.

In point of fact, the odds are that the Democrats will be favored by that balance. The Senator, indeed, already makes the fact plain. Naturally, he would prefer it that way; would like, when the end comes, to lie in state in all the pomp and circumstance of public mourning as a Democratic chieftain. As I write, the Democrats, like the burghers of Paris when Gargantua lifted the bells from Our Lady, have no choice save to send their sophisters to wait, cap in hand, for audience. Terms will come high; they will contemplate much genuflection, much bending of the pregnant knee, the crucifixion of the dreams of the staunchest white hopes of the party. The test will come in 1930 when the Senator stands for reelection. He will demand the nomination without opposition; if he is opposed, he will almost certainly win, since the Republicans openly announce their intention of invading the Democratic primaries to support him, and, if he wins, his revenge will be exacted with rack and wheel. If the Republicans are barred and he is cheated of the nomination, he will, according to his supporters, run as an independent; in that case, the Republicans promise to withhold a candidate of their own and give him their support, which will mean his election. Possibly, of course, this Republican promise merely hides an intention to run in a candidate of their own at the last moment and take advantage of the Democratic dissension to seize power for themselves. But in no case is the outlook happy for the Democrats.

How complete is the Senator's power is well shown by two incidents in the politics of the State. The first of these deals with the fate of a bill in the General Assembly of this year. It was an innocent-seeming bill, providing simply that a voter participating in a primary of any party must take an oath to support that party in the ensuing election. In fact, it was aimed at Simmons; it served notice on him that he would not be allowed to capture the nomination through Republican votes, it thumbed the Democratic nose at him. Well, it died--smothered, not by brazen-faced Republicans, not by cadaverous Jesuit-swatters and convent-burners, but by impeccable Democrats.

The second incident concerned the ruling of the State's

Attorney-General that, under the law, McNinch, as chairman of the

Anti-Smith Committee, must file a report of his receipts and

expenditures in his cam-

THE AMERICAN MERCURY 318

paign against the Pope. This, too, was a gesture of hate, designed to discredit McNinch and Simmons by establishing the financing of the Anti-Smith campaign by the Southern Power Company, which had obvious fish to fry. As to the truth of that charge I cannot say here, beyond the observation that the committee seemed untroubled by poverty, for McNinch defied the ruling and added insult to injury by publicly taunting his foes. Not a hand has been raised to force an accounting from him, nor, indeed, has the matter been so much as cheeped since.

The breach in the party, I believe, is too wide ever to be closed. Simmons will fling his bridges across it for the service of his ambitions and those of McNinch and Hampton, but I doubt that reunion will be forthcoming. His position would be too vulnerable, once he lost the support of his present following, a remarkably cohesive one, made up of professional sword-swallowers and congenital morons, all violently enamoured of Great Moral Ideas, the Parsons and the Senator, and conscious, to a man, of acute antagonism toward the regular Democratic forces. Indeed, in view of that last, I doubt that even Simmons, if he desired it, could restore the bells to the towers of Our Lady, for the pure in heart seem destined to merge eventually with the Republican party and thereby establish the latter's control of the State.

Spiritually, and often enough in fact, they are the descendants of the Know Nothings of the '5o's, a group which was strong in the State. Hate for Catholicism is their inheritance. They have been held in the Democratic party through tradition and the feeling that it was peculiarly the party of the South. But, unless I miss my guess, control of it will not soon return to the South, and, though it will not care to nominate another Catholic, it obviously is not, under its present leadership, going to repudiate its action in nominating the last one, the only possible thing that could clear it of the sour suspicion of these hinds. Tradition, violated once, will not again deter them from expressing their apprehension at the polls. Moreover, many of them are women who voted for the first time under the compulsion of balking the Pope; they will continue to vote and, because the Democratic party was the object of their suspicions in their first experience with politics, they will continue to regard it with jaundice. The entire group shows the tenacious fidelity to a single idea characteristic of Freudian cases in general.

Nor is it any more a blushful matter to be a Republican in the State; it is even a little smart. The party has been so thoroughly fumigated of the smell of niggerwool that many of its more recent actions suffer, like Charles Sumner, exquisite anguish at a whiff of Moor passing on the other side of the street. The old goddamning, peanut-cracking, heavy-breathed atmosphere of its sessions in the days of the sockless bureaucrats are no more. Stuart Cramer, a cotton-mill princeling who aspired to Hoover's Cabinet, and Charles A. Jonas, new Republican Congressman from the rock-ribbed Democratic Ninth, have taken charge, and with them they have brought the silken pomp of the directors' room. Ward-heelers take off their hats and throw away their cheroots when they drop in nowadays.

The cotton-mill captains of the State, almost to a man, have moved their membership over from the Democratic party; the bankers, merchants, newspaper publishers and business men in general are following suit, particularly in the larger centers; only the conservative professional classes and the not-yet-rare sleepy little towns, untouched by industrialism, still cling unshaken to the old love. Republican rolls, once dedicated to niggers, hill-billies and other such pariahs, begin to smack of the Social Register.

The dread handwriting is on the wall: North Carolina is going Republican.

Go to Top of Page Go to Top of Article

Go Home Go to next article: "The Mind of the South"