![]()

The Charlotte News

Tuesday, April 15, 1941

FIVE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The case to which "Curbed Power" refers is Nye v. U.S., 313 U.S. 33, in which the Court held that the words of the Federal contempt statute, that contempt powers of Federal courts "shall not be construed to extend to any cases except the misbehaviour of any person or persons in the presence of the said courts, or so near thereto as to obstruct the administration of justice", referred to physical, not causal, proximity, in fixing the limits of the power. And thus an order of contempt in a North Carolina case in which two individuals, not related to the case, procured, through "liquor and persuasion", the dismissal of a lawsuit brought by the father of a decedent son as part of the estate administration, claiming that the headache remedy B.C. caused his son's death, while constituting conduct tending to interfere with the administration of justice, was nevertheless not a matter punishable as contempt as the conduct persuading and aiding the dismissal was not "so near" the court physically as to be within its power to exercise jurisdiction for purposes of finding contempt. (Whether, incidentally, part of the "persuasion" was music by Faron Young, we don't know.)

The column, as the piece indicates, had inveighed several times earlier against the use of contempt powers to punish out-of-court comments critical of court decisions; for instance, in "Contempt", February 4, 1940, and "No Hard and Fast Rule", August 29, 1938, both regarding the Los Angeles Times cases, eventually decided December 8, 1941 by the Supreme Court in favor of the Times in Bridges v. State of California, 314 U.S. 252, an opinion also deciding the related case of a contempt citation against West Coast maritime labor leader Harry Bridges for having wired to the Secretary of Labor Francis Perkins a critical statement of a court ruling, that having been discussed in "New Role", October 19, 1940.

As to the first piece, Cash had mentioned in The Mind of the South Senator Glass as one of the early opponents to the Klan mentality which went hand-in-hand with the obscurantism precipitating the Fundamentalist anti-evolution movement:

One of them is that as time went on, opposition to them steadily gathered head in the South. There had been opposition from the first, of course, and outside the schools, where it naturally flourished vigorously. Many thousands of the older men bred in the best tradition of the South (and regardless of whether they belonged to the old aristocratic or semi-aristocratic orders or were plain people), remembering the abuses and outrages which had disgraced the early Klan in its later days, distrusting the use of the state's power for allegedly religious ends, or thinking sagely that the schools themselves were the best judges of what they should teach, refused to have anything to do with either movement or in any way to lend them approval. So did thousands of the younger men, either because of their tradition or because they had--often quite unconsciously--come to some extent under the influence of the new tolerance centering in the schools. And some of them were courageous enough to speak out their convictions: editorial writers like Gerald W. Johnson and Nell Battle Lewis in North Carolina; Douglas Freeman, Virginius Dabney, and Louis Jaffé in Virginia; Julian Harris in Georgia; and Grover Hall in Alabama; ministers like Baptist Edwin McNeill Poteat of South Carolina; politicians like Carter Glass of Virginia. Indeed, such men had such complete control in Virginia that neither movement ever got thoroughly established there.

But with the passage of time more and more men of serious intelligence began to heed the warnings of these, to examine into the movements, and to realize their implications for the South. In Alabama, Grover Hall, whose long series of editorials against both in the Montgomery Advertiser was to bring him the Pulitzer prize in journalism, won increasing support not only from the Birmingham Age-Herald and News but eventually, so far as the Klan went, from most of the dailies in the state. In Georgia, Julian Harris, who had long waged his fight against both the Klan and the whole Fundamentalist position single-handed, was joined by the Macon Telegraph and other papers in the battle on the Klan. In Tennessee, the Memphis Commercial-Appeal at length took up the cudgels against the Klan, but it continued to give its blessings to the anti-evolutionists. In Alabama, Senator Oscar Underwood unloosed scathing rebukes on the Klan, though he knew probably it meant the end of his Presidential ambitions. In Georgia, Governor Thomas W. Hardwick ordered the Klan to unmask, knowing certainly that it would close his political career. And so it went.

And seeing these take their stand, still others began to pluck up heart, to venture opposition in private at least. More, many of the leaders of all sorts who had joined the Klan or trafficked with it, began to get out of it or back away from it, and something of the same sort began to happen among those who had gone in for Fundamentalism and its politics--in part because they were disgusted with the crimes of the Klan, and ashamed before the amazed laughter of the civilized world at the "monkey laws" and the Scopes trial, in part because of canny doubts about what the eventual outcome might be for themselves. And after 1925 a rapidly growing exodus of all the more decent elements from the rank and file of the Klan would begin.

In the very hour when they seemed to have it in their power to do what they had plainly set out to do, the people themselves showed a curious hesitancy and revulsion--a strange unreadiness to go through with it. The same disgust for the Klan's crimes and the same proud shrinking from the thought that the South was being treated as a comic land because of the anti-evolution laws and attacks on intelligence, which assuredly moved some of the leaders, probably had something to do with that in the more informed levels in general. The old respect for Education, reasserting itself continually, entered into the equation, too. After all, men of native good sense and decency everywhere felt themselves bound to respect such men as Poteat of Wake Forest, and Harry Woodburn Chase and Frank Porter Graham of Chapel Hill, however much they were opposed to them--felt dimly in the depths of their minds, when they saw them come boldly out in defense of academic freedom, that they might know better what they were about than had been supposed. And beyond even that, it is not improbable, I believe, that the modern mind itself, the spirit of the world in the time in which they lived, had in some imponderable measure touched even the simple also, had all unconsciously entered into them to plant the tiny germ of inward doubt. Perhaps the very Klan and Fundamentalism themselves testify in the end to the beginning of the subtle decay of the old rigid standards and values, the ancient pattern; perhaps they proceeded from that distrust of themselves which I have before noted in Southerners, and represented an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to draw themselves back upon the ancient pattern to escape the feeling that, against their wills, the seeping in of change might claim them also. Perhaps they stood at last, these people, bemused before their own minds, condemned to inactivity by the sweep of current and counter-current through them.

--The Mind of the South, Book Three, Chapter II, "Of Returning Tensions--and the Years the Cuckoo Claimed", Section 26, pp. 339-341

Nevertheless, when it came to the 1938 Wagner-Van Nuys anti-lynching bill, Glass stood in opposition, albeit not necessarily at the time, depending on rationale, as Cash was quick to point out, a Neanderthaler's exclusive claim:

For my own part, I have always been doubtful of schemes for Federal control of lynching, fearing that their net effect on the South would only be to rouse its trigger-quick dander, always so allergic to the fear of Federal coercion, and so tend to increase rather than suppress the practice. But that does not change the fact that the stand of the Times-Dispatch was an unusually courageous sort of journalism.

--Book Three, Chapter III, "Of the Great Blight--and New Quandaries", Section 9, p. 373

The rest of the page is here.

![]()

A Libel

Glass Might Best Resent This by Leading the Fight

We shouldn't blame Senator Carter Glass of Virginia if he sued the pipsqueak columnist who (in another paper) we find saying that Robert Rice Reynolds is a sort of Carter Glass Democrat--one who likes the President personally but has opposed his domestic and foreign policy.

Senator Glass has opposed the domestic New Deal often and bitterly (Reynolds has generally supported it). But it is simply not true that Glass has opposed the President's foreign policy. On the contrary he has been one of its most enthusiastic supporters, and the only fault he has ever found with it was that it did not go far enough to suit him.

And as for the suggestion that there is any comparison between the two men--ah, well, in the days of old John Randolph that would have been the occasion for pistols for two and coffee for one at dawn. Senator Glass is a man of great intelligence, integrity and dignity. His political enemies respect him as warmly as his friends. But is there anybody who actually respects Robert Rice Reynolds?

He is a thoroughly trivial man with cynical and dangerous ambitions.

In point of fact, Senator Glass seems to us to be the obviously indicated man to lead the flight, which appears to be in the making, on the elevation of Reynolds to the post of chairman of the Senate Military Affairs Committee.

As much as any Senator, Glass has stood above the shabby business which is called practical politics. He must see as clearly as any that mere seniority is no excuse for placing a man like Reynolds in a key position in time of national peril. And he has precisely the bitter and pungent gift of speech which is needed to show up the preposterousness of the whole affair.

![]()

Curbed Power

Court Restricts Contempt to Vicinity of Courtrooms

The Supreme Court yesterday destroyed an abuse which The News has often called attention to--the misuse of contempt of court powers by judges.

The court held that summary punishment for contempt can be meted out only if the alleged offense was committed in the vicinity of the courtroom. If there is genuine obstruction of justice elsewhere it must be dealt with under the written criminal statutes and not by the judge's arbitrary decision.

This is plainly the rule of common sense. The contempt of court power, which is the only instance of arbitrary power still allowed to judges in a democracy, is permissible only because it is necessary to insure that trials shall proceed in an orderly fashion and without interference or intimidation. To extend it beyond the courtroom and its vicinity is simply to open the way for the judge to become a tyrant who allows no criticism of himself.

It has already been working out that way. In St. Louis when an editorial writer and a cartoonist of the Post-Dispatch attacked a judge who was the stooge of the city's worked political machine, they were promptly hauled before that judge and sentenced to jail terms and fines. And the Los Angeles Times now has an appeal pending from a conviction for contempt for criticizing a court's behavior in a trial--after the trial had ended.

The court reversed a 1918 decision, in the case of the Toledo, Ohio, News, which had furnished basis for these dangerous encroachments. Such reversals furnish ground for renewed faith in the ultimate good sense of democracy.

![]()

Brash Claim

But This Sort of Thing Nevertheless Has Its Uses

The most brazen thing which has come out of Fascism and Nazism is the current yammer from Berlin and Rome about the protectorate established over Greenland by the United States. Both governments are full of moral indignation over what they call a cynical violation of international law. And the Nazi stooges who make up what is called the Danish Government chime in.

If terror and tragedy did not march behind all this, it would be uproarious comedy. It is of course strictly legal, that occupation of Denmark by the Nazis, the rape of a dozen nations. It is, of course, comity in accord with international law that the chosen victims of the Nazi attack are always women and babies. And of course the submarine attack without warning is strictly in accord with the Hague Convention. These swine have contemptuously destroyed the whole structure of international law, and now dare--lyingly--to appeal to it when it interferes with their precious schemes for power and loot.

But there is method in their madness. They judge, and quite correctly, that there are many people in the United States who are willing and eager to listen to them and go around--without having the least notion what they are talking about--yelping that the Administration is robbing poor Germany and Italy and Denmark of their lawful rights and setting up as an imperialistic land-grabber.

There is only one comfort in the case. The uproar is pretty good evidence as to exactly what Germany did have in mind for Greenland.

![]()

Rash Risk

The Dangerous Wonders Of Science Grow And Grow

Doc Martin and Doc Thompson had better take cover--fast. They are in actuality far too dignified in general to be styled "Doc." They are Dr. Gustaf J. Martin and Dr. Marvin R. Thompson, of the Warner Institute for Therapeutic Research, in New York. But when they get through with this, they are likely not to be so dignified. That is, when the WCTU, et al., gets through with them.

For years, it has been a well established rule of medicine, law, morals, ethics and all points east, that the really great force for temperance in alcoholic liquors in this country was the hangover. And now this pair comes along and proposes to abolish the hangover, just like that. That is, provided the salted one is not too blotto to take his medicine before going to bed.

Specifically, what they have done is to work out a "detoxicant treatment," which consists in injecting into the veins of the patient large quantities of artificially-made detoxifying fluids normally found in the body. The treatment is good for many things--burns, shock, the reaction on some people of useful drugs, the toxemia of pregnancy, etc. But its effect on the hangover is its most startling claim to fame. If the bad boy takes it before he goes to sleep, he "awakens feeling completely normal."

At least we find as much reported by the sober-sided Associated Press. We do not vouch for it and carefully disclaim all responsibility in the premises.

But if the thing should turn out to be true, we shudder to think of the coming battle to prohibit it. For it seems reasonably clear that a lot of depraved souls are going to conclude immediately that all that is now lacking to make this a perfect world is a way to scotch Hitler and a way to make hair grow on bald heads.

![]()

![]()

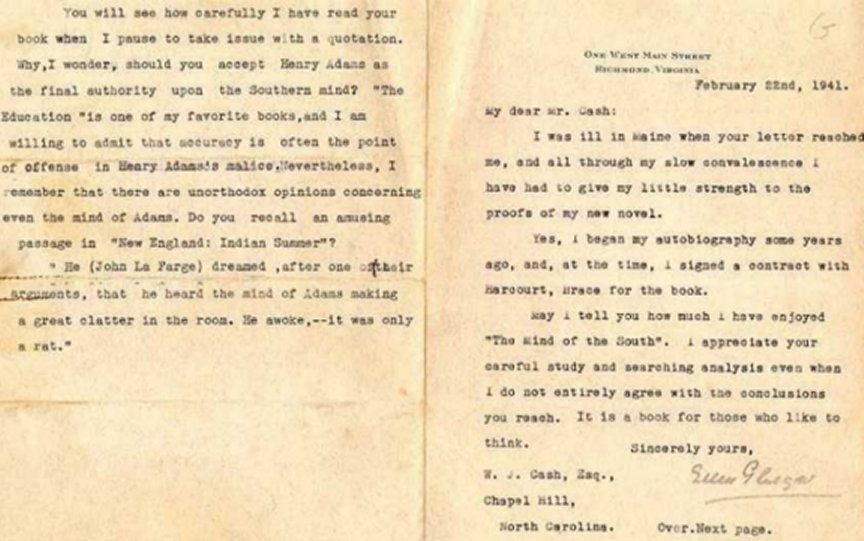

Site Ed. Note: As we mentioned in our note associated with March 14, 1940, Ellen Glasgow had communicated with Cash regarding The Mind of the South on February 22, 1941. The brief letter, including its puzzling comment anent John La Farge's dream about a rat, which does not exist in fact within the pages of The Education of Henry Adams, either in the chapter she references or elsewhere, is reproduced below.

The book which finally earned her notice from the prize committees, including, later in 1941, a Pulitzer Prize, was In This Our Life. For Ms. Glasgow, 79 at the time, it would be her last book; she died in 1945.

![]()

Late Award

Miss Glasgow Should Have Had Honors Long Ago

The selection of Ellen Glasgow for the 1941 Saturday Review of Literature award "For Distinguished Service to American Literature" is belated and somewhat inadequate recognition of the great Richmond novelist.

Miss Glasgow was the first Southern writer to break out of the sentimentalized tradition of Thomas Nelson Page and treat Southern people as recognizable human creatures instead of romantic stereotypes.

But despite her pioneering, despite the fact that she has turned out a great volume of work over the past 40 years which constitutes exactly what she planned in her youth, "A Social History of Virginia"--perhaps the closest thing to a Comédie Humaine yet produced in America--, and despite her great skill in writing, she has been uniformly neglected by the various prize committees which arrogate to themselves the right of naming the "best" authors. The Nobel Committee can reach out and tap Pearl Buck for one good book but has apparently never considered Miss Glasgow. And though the Pulitzer Committee has tapped Margaret Ayer Barnes, Louis Bromfield, and Margaret Wilson, it has never crowned one of Miss Glasgow's books--a neglect she shares with Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, William Faulkner and Theodore Dreiser.

It is pleasant to see that at least one group of editors has at length got around to appreciating her true stature.

![]()

![]()

![]()