![]()

The Charlotte News

Saturday, December 9, 1950

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports that allied artillery and warplanes, grounded by weather on Friday, hit the enemy hard in an effort to eliminate their block of the icy road leading to escape from the trap near the mountain town of Koto, into which 20,000 American Marines and infantrymen of the Tenth Corps were encompassed. The trapped troops were reported close to linkage with the Third Division, moving northward from the evacuation port of Hungnam to rescue the force via waiting ships. Some of those trapped were thought perhaps to have already joined with the Third Division.

Correspondent Stan Swinton reported that 32,000 to 40,000 Chinese Communist troops were striking swiftly within the hills flanking the river gorge road south from Koto, to cut the escape route far behind the two American columns. Allied artillery, however, pounded the enemy positions in the hills throughout the night, as the Americans fought off a night attack on the northeast edge of Koto and the airfield there, still needed for evacuation of wounded, was for a time shut down, later reopened.

Correspondent Jack MacBeth, the only correspondent with the surrounded troops, reported that they had pushed three miles south of Koto along the narrow and slippery river gorge road, as the Marines seized the high ground to protect the retreat. He offered that chances appeared good, albeit costly in casualties, that they would break through the Chinese forces, but apparently was not aware of the new threat posed by the four or five flanking Chinese divisions down the road, as reported by Mr. Swinton.

MacArthur headquarters in Tokyo suspended its daily briefings for the nonce, presumably for security reasons. Shortly thereafter, the British commander, Lt. General Sir Horace Robertson, said that the need for censorship of press accounts was increasing, a sentiment echoed by all of General MacArthur's information officers. But, for the present, the non-censorship rule of General MacArthur established early in the war continued. The daily handouts of printed material continued, but at the briefings, reporters were afforded opportunity to ask questions.

Secretary of Defense Marshall announced that the President was seriously considering declaring a national emergency. He had testified in executive session earlier before the Senate Appropriations Committee, and was urged by Senator John McClelland of Arkansas to exert pressure on the President to accelerate military production to wartime levels to avoid the spread of war. He reportedly responded that a base for total mobilization would be laid in production acceleration under the proposed 18 billion dollar military budget, but that no decision had been reached on moving to full mobilization.

At the U.N., upon the opening day of debate on the six-nation resolution to seek withdrawal of the Communist Chinese from Korea, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Vishinsky continued to insist before the General Assembly's political committee that the Chinese Communists in Korea were volunteers, but admitted that they had been formed into organized military units and integrated with the North Korean army. He also claimed that Britain and the U.S. had violated the U.N. Charter and were denying the right of the Chinese to defend their own threatened border.

The answer from Communist China to the 13-nation Asian and Middle Eastern proposal to stop its advance at the 38th parallel had reportedly been received, but there was no indication yet of the answer.

Might have to wait two and a half years on that one.

The President and Prime Minister Clement Attlee held open the possibility of settlement of the Korean conflict and other crucial world issues, as long as there would be no appeasement and that the Communists would modify their conduct in the interests of peace. The communique from the White House deliberately avoided reference to the Chinese, referring only to "intervention" in Korea and "aggression" by the Chinese.

Secretary of State Acheson stated in executive session to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, meeting with House Foreign Affairs Committee members, that the U.S. would not engage in appeasement in the Far East, that the same unwavering stance against aggression and imperialism had to made there as in the West. He also asserted that the work of NATO could proceed at a faster pace as a result of the Truman-Attlee conference just concluded during the week.

In response to the joint Truman-Attlee statement of the previous day, three Republicans, Senators Robert Taft, Alexander Wiley and William Knowland, advocated arming of the Chinese Nationalists on Formosa, that they might fight in guerrilla warfare against the Chinese Communists on the mainland. They said that they were not content with leaving protection of Formosa to the U.N.

Harry Gold, the research chemist who had been charged with espionage in wartime for giving the Russians nuclear secrets and who had pleaded guilty, was sentenced to 30 years in prison. He said that his crime had been a "terrible mistake", a fact of which he had been convinced by observing the way his court-appointed counsel had worked on his behalf despite personal criticism and invective—his toward them or theirs toward him, not being clear, as both forms in the two-way street are wont to happen. He said that he had sought to make amends by relating of the entire spy ring for which he was courier and identifying everyone involved. The crime carried the possibility of imposition of the death penalty. The spy ring included the already indicted Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, both of whom would later be convicted, sentenced to death and executed in mid-1953.

All 39 aboard a passenger plane which crashed in Africa were feared dead.

On the South Side of Chicago, a four-story tenement caught fire, killing eight persons, including a family of seven. Firemen were searching for additional bodies among the 200 residents, some of whom had fled via fire escapes. Some victims had leaped to their deaths from upper floors.

Near Monsan, Mass., seven people homeward bound in a jeep from a birthday party died in a three-car accident. Five persons in the other two vehicles were injured.

Seven in a jeep? They may have seen one too many war pictures. Guess they won't attend any more.

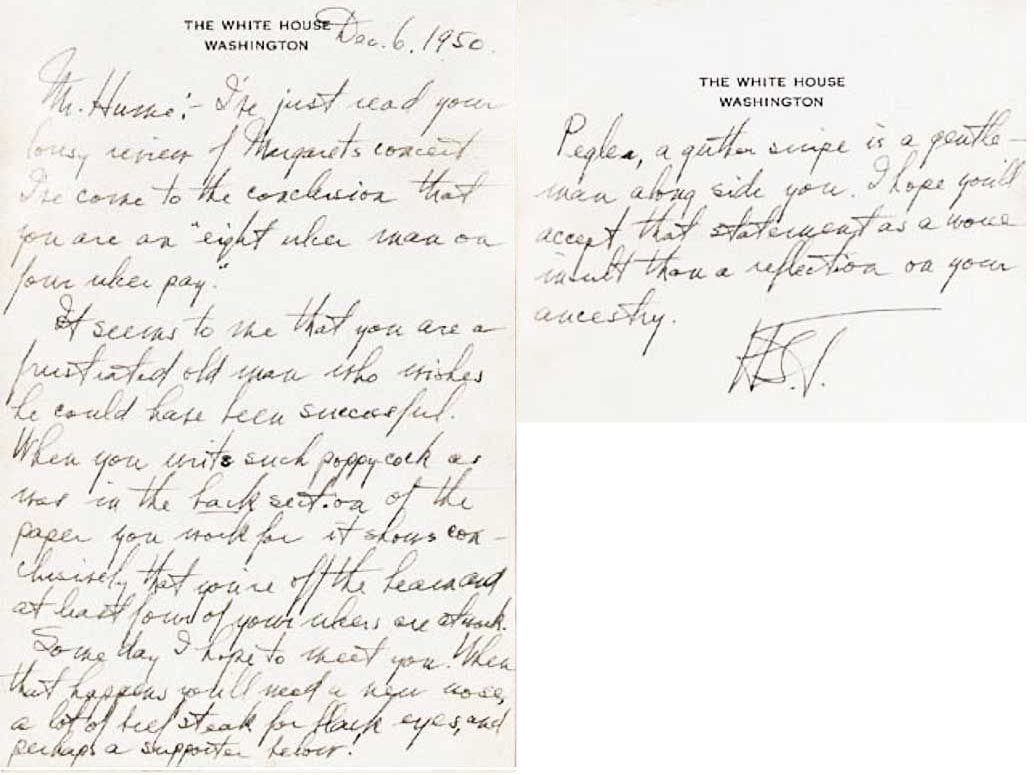

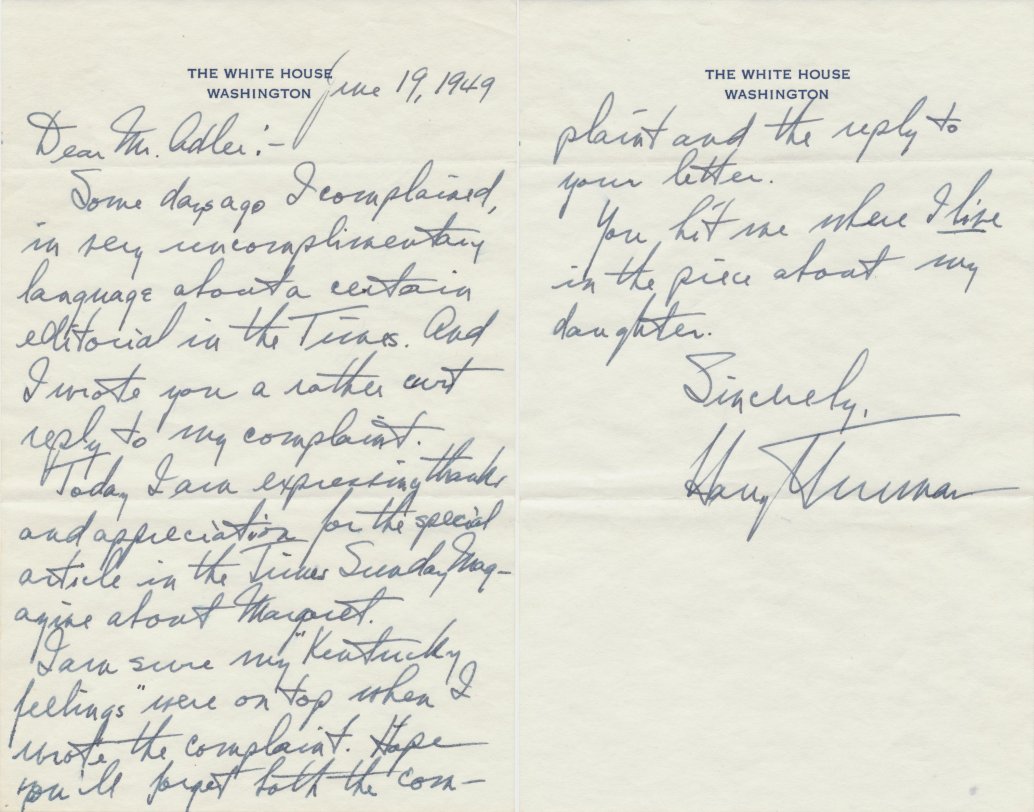

The President, upset about a less

than glowing critique of daughter Margaret's operatic recital in

Washington, fired off a fiery response to the critic, Paul Hume

Oh, that's hitting below the belt.

The report notes that Mr. Hume was 32 years younger than the 66-year old President and weighed at least 15 pounds less than the Chief Executive's 180-plus.

Mr. Hume said that the published

version was similar but not identical to the actual handwritten

version he received. Some who had seen the original claimed that it

was "more earthy". Mr. Hume excused it as an "outburst

of temper" which the President ought be allowed, especially

during a world crisis and after having just suffered the loss of his

close personal friend

Republican Senator Arthur Watkins of Utah called the written outburst that which the public had come to expect from the President when "his guardians were not there to take care of him." Other Republicans recalled his referencing Drew Pearson as an "S.O.B." for criticizing the receipt by military aide Maj. General Harry Vaughan of a decoration from Argentine dictator Juan Peron the previous year.

Democrats dismissed it as a proud father defending his daughter, and some chuckled and mused that it was reminiscent of the way Andrew Jackson might have responded.

Ms. Truman, herself, in Nashville on tour, said that Mr. Hume was a fine critic and had a perfect right to say what he thought.

The President had also suggested in the letter that "guttersnipe" Westbrook Pegler was a gentleman by comparison to Mr. Hume, which he hoped would be accepted "as a worse insult than a reflection on [his] ancestry."

Mr. Pegler, a conservative columnist who was usually critical of the Administration, responded that it was "a great tragedy that in this awful hour the people of the United States must accept in lieu of leadership the nasty malice of a President whom Bernard Baruch in a similar incident called a rude, uncouth, ignorant man."

Author William Faulkner was in

Stockholm to receive

There was no elucidation of the national weather picture

On the editorial page, "Anglo-American Unity Preserved" discusses the report emerging from the Truman-Attlee talks, which had made several substantive remarks, including assurance that the U.S. and British were in agreement on all major policy goals, even if there were differences on how to deal with China. It pledged continued support of the U.N. and promised that there would be no appeasement. It also called for early appointment of a supreme commander of NATO and set forth agreement on allocation of strategic raw materials across the world and on standardization of weaponry. It also encouraged China and Russia to modify their policies to make defense preparations unnecessary.

The piece finds it encouraging to have a reaffirmation of Anglo-American unity but ventures that it would mean little unless the two nations shifted their defense programs into high gear.

"Eisenhower's Services Needed" finds that the Truman-Attlee agreement on immediate activation of the Western European defense program under the command of General Eisenhower was encouraging. It urges that no time should be wasted in appointing General Eisenhower to the post, as no appreciable progress could be made on rearmament until that took place.

Joseph C. Harsch of the Christian Science Monitor had said that doing so forthwith would demonstrate to the world that the U.S. was not interested only in Asia and had not been panicked by its misfortune there. The magic of the familiar Eisenhower name would inspire confidence in Western Europeans. With a compromise satisfactory to the French regarding German armament having been worked out, the way appeared clear for the appointment.

"Another Call for UMT" tells of the Association of American Universities recommending universal military training for young men reaching age 18. It was the same proposal made recently by Dr. James B. Conant, president of Harvard. It finds it significant that the nation's educators, previously opposed to UMT, had now understood the national emergency sufficiently that they favored it.

A piece from the Washington Post, titled "Can't Keep a Secret", tells of it being disgraceful that General Omar Bradley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, could not testify in secret before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee without having his remarks twisted and told to the world. One of the five Senators present at a hearing the previous Tuesday had told of General Bradley's contingency plan for evacuation of the troops, which General Bradley later corrected to mean only those Tenth Corps troops trapped in the northeastern sector of Korea and not a general evacuation.

It was the third time that General Bradley had his secret Congressional testimony revealed. A year earlier, Senator Kenneth Wherry had leaked to the press General Bradley's testimony regarding Russian armed strength. The previous March, Senator Elmer Thomas revealed what the General had said to a Senate Appropriations subcommittee regarding the explanation of war outlook. Neither of the Senators was present at the Tuesday session and so could not have been the revealing party.

The result was that in the future, the Senate would likely not receive frank testimony from military leaders. The piece thus favors ferreting out who the Senator was who revealed the information and disciplining him.

Drew Pearson informs that those who sat in on the Truman-Attlee talks found that they had set a new high-water mark for Anglo-American cooperation. But despite the agreement on economic cooperation and quick rearming of Europe, they remained at odds regarding China policy. A joint policy on the intermediate problem in Korea was a lot easier.

Initially, Mr. Atlee favored a complete withdrawal from the peninsula, supported by Joint Chiefs chairman General Bradley and the Joint Chiefs, who felt that it would cost 50,000 allied casualties to defend even a small beachhead. The British chief of staff, Field Marshal Sir William Slim, also agreed.

But Secretary of State Acheson favored maintaining the beachhead on the ground that to withdraw would leave the Western allies untrustworthy as allies throughout Asia. It would be better, he counseled, to go down fighting than to turn and run. Eventually, Mr. Attlee came to agree with this position. The Joint Chiefs advised that with enough warships and planes, they could hold a beachhead indefinitely.

Mr. Acheson favored a tough stand against China, calling for a naval blockade and using Chiang Kai-Shek's air force to bomb Chinese targets. Mr. Attlee opposed that plan on the basis that it would thrust back China from the negotiating table, that a blockade would not work, that the U.N. would not approve it, that the tactics would alienate other Asian countries and would drive China into the Russian sphere. He urged that normalized relations, by contrast, would potentially lead China to become as Tito and Yugoslavia, turning against the Soviets.

The President and Mr. Attlee postponed any decision on China as a result of these differences.

Senator Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska was rendered speechless by a German reporter, who, after telling him that Germany was tired of fighting and, after being asked by Senator Wherry what it would take to get them to fight, saying that it would take two or three American divisions. Senator Wherry then said that there was not enough money to maintain those numbers of troops, at which point the reporter commented that there had to be, with all the television antennas he saw on American rooftops. At that point, Senator Wherry did not know what to say.

Joseph & Stewart Alsop tell of a "liberation" army of 200,000 seasoned Chinese troops standing poised in south China to advance in Indo-China. Thirty Indo-Chinese Communist battalions trained in China, sprinkled with Chinese artillerymen and technicians, had already crossed the Indo-Chinese border. A Russian military mission headed by a Soviet major general had already arrived at Nanning in south China to supervise the new Kremlin enterprise. As one compared these facts to the preparation for the similar Chinese onslaught ongoing in Korea, it was likely that the offensive would soon begin in Indo-China.

Originally, Korea and Indo-China had been pegged, during the Peking conference the prior April, as the first joint targets of aggression, with Ho Chi Minh and Mao Tse-Tung having agreed on the present preparations for the offensive into Indo-China.

A few weeks earlier, the Chinese Communist government had protested violations and raids on the Indo-Chinese border in language reminiscent of that used in their protests regarding Korea. In the U.N. Security Council, the Communist Chinese lead delegate, General Wu, had stated that the Chinese would "liberate" Indo-China as Korea had been.

There would be no hope that the battered 150,000-man French colonial army in Indo-China could withstand such an attack for very long. Every informed observer agreed that if Indo-China fell to the Communists, then so, too, would all of Asia. The weaker nations of Western Europe would inevitably follow.

We're done fer. It's over. We give up.

They suggest that such was the possible or even probable future by which the talks between Prime Minister Attlee and the President would be judged.

The American policymakers had no ready plan for dealing with the Chinese aggression in Korea. Use of allied air forces could provoke retaliation by the Soviets who had air forces, albeit inferior to those of the allies, in Siberia and Manchuria, probably to be utilized in the event of such allied bombing operations.

The British realized that everything now had to be sacrificed to national security but, even so, understood that it might be too late, in light of the enemy preparations for an Indo-China offensive, indicating acceleration of the Soviet timetable beyond anything anticipated even by the worst pessimists.

The Alsops suggest that if this offensive were to begin during the winter, the Red Army, itself, would likely become involved in the fray by spring. The nation thus was threatened with general war which the President and Mr. Attlee had not yet found a means to avert.

Robert C. Ruark believes that the newly invented mechanical heart would set back romance. It had been found to keep a dog alive for 71 minutes and could conceivably therefore take a corpse from death's door back to the land of the living long enough for repair of vital organs.

He finds all of the songs wrong in stressing the heart as the center of love emotions, thinks it instead the stomach. He found it to be as an attack of "green-apple misery" rather a swift pain of the aorta.

What kind of romance have you been seeking?

He suggests that now a broken heart could be repaired by a mechanic. He wonders how one would warm the cockles of the heart with a blowtorch.

"Atom", which once meant tiny, now connoted hugeness and horror. Similarly, the heartbeat now sounded as a machine foreseen by Walter Mitty. There were also mechanical brains which could do the thinking for man. Man was obviously becoming quickly obsolete.

"Ah, me. My heart is sick. I suspect it's because somebody just fed it a dose of emery dust, or forgot to strain the high octane that runs it."

Tom Schlesinger of The News, in his weekly "Capital Roundup", tells of both Senators Clyde Hoey and Willis Smith believing that the time was not ripe for dropping the atom bomb. Some Senators were calling for its use in "anticipatory retaliation". Senator Hoey favored its use in the event of a general war against Russia, but Senator Smith said that he had always opposed it, but that circumstances could change.

Senators Smith and Hoey both opposed statehood for Hawaii and Alaska, favored by former Senator Frank Graham.

Senator Smith would likely serve on the Judiciary Committee, where both Senator Graham and predecessor Senator J. Melville Broughton had served.

Senator Smith's Congressional aide would not be named until January.

Wonder who that's going to be.

S. T. Henry, the editor of the Tri-County Weekly, was in Washington to meet with National Security Resources director Stuart Symington and others to try to stimulate interest in a fresh-water defense industry to remedy unemployment of 3,000 persons in Spruce Pine.

None of the members of the North Carolina Congressional delegation planned to leave Washington prior to December 20, in light of the dire Korean situation.

Senator Smith said that he had never read The Road Ahead by John T. Flynn, which had attacked Senator Graham as a Communist sympathizer and had been distributed widely as part of the Smith campaign. He said that he had received complimentary copies and had read underlined passages.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()