![]()

The Charlotte News

Tuesday, June 6, 1944

ONE EDITORIAL

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page and the inside page report of D-Day and H-Hour having arrived, the invasion

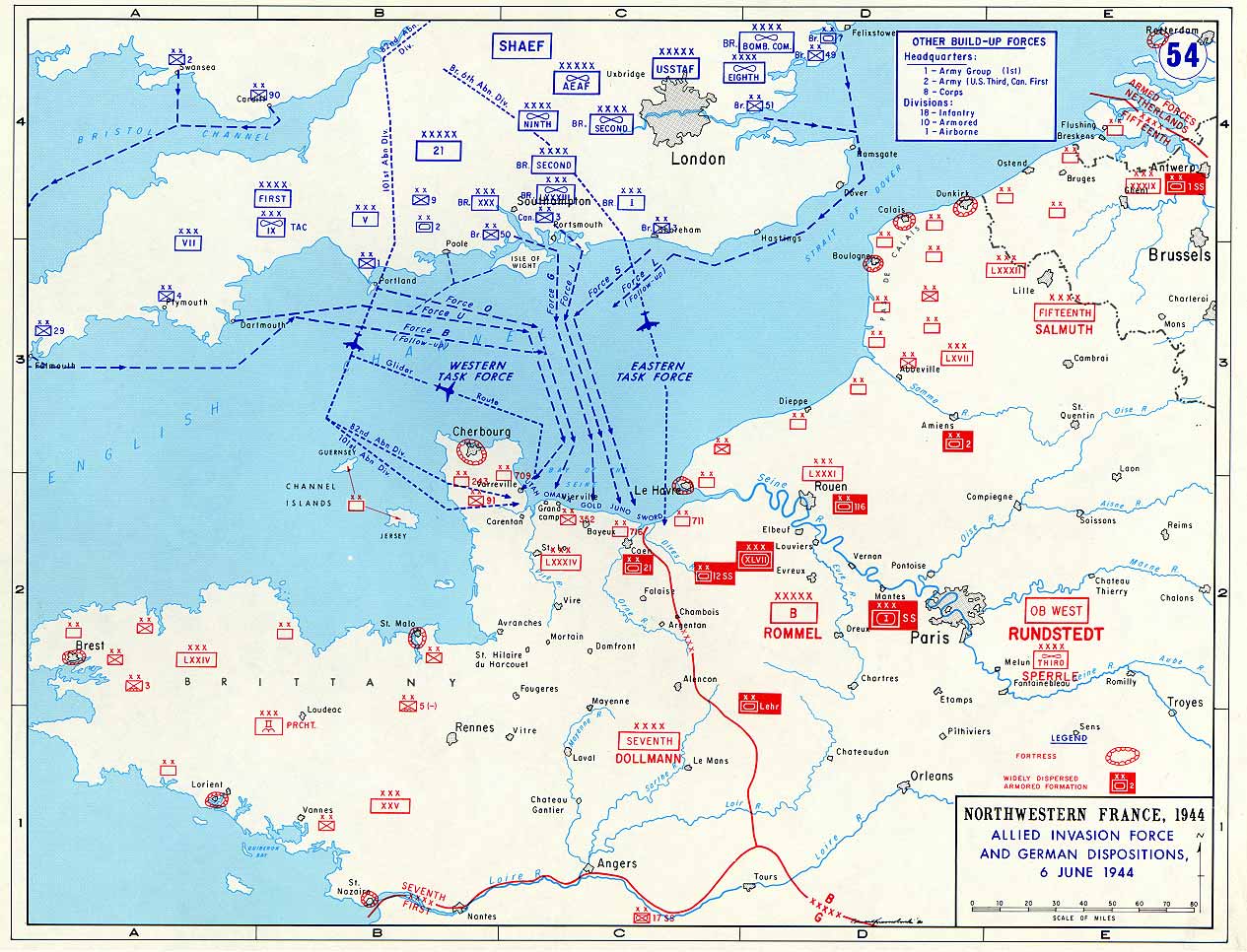

The greatest part of the preliminary bombardment from large ships came from the Royal Navy, which struck the coastal emplacements of the Nazi West Wall. Then came an air assault dropping 10,000 tons of bombs, the most during the war, meeting only light resistance from the Luftwaffe which, despite having available 500 bombers and 1,750 fighter planes in the area, flew only 50 sorties. The Allied fighter planes, as a result, were said to have little to do.

To avoid the tragic confusion of Sicily the previous July with the two friendly fire incidents, at Catania and Gela, the invasion force planes bore a distinctive zebra striping to distinguish them from Luftwaffe.

Finally, after deployment of the airborne troops, came the amphibious landing craft, the Elsie's and LCVP's, which dotted the water all along the beaches of Normandy, bearing the familiar codenames, "Utah" on the Cherbourg Peninsula, "Omaha", to its east, where the largest contingent of troops landed, 34,250, and the greatest loss of life occurred, "Gold", "Juno", and "Sword", the latter three being where the British Second Army troops landed, each beach easterly of the other along the broad cove between Cherbourg and Le Havre.

Behind Utah Beach, to its west, the 82d and 101st American Airborne Divisions sent paratroops and glider-borne troops, with their cricket signaling devices, behind the German lines against "faintly moonlit" skies to pinch the German defenses and ease the landings, while gaining a foothold to prevent flanking attacks. In some places, dummy paratroops, shrouded in artificial fog, were dropped to confuse the enemy. The American airborne forces sufered about 2,500 casualties, of whom 238 died.

British 6th Airborne troops, numbering four divisions, 7,900 men, dropped behind enemy lines to the south between the Orne and Seine River estuaries, penetrating as far as Rouen and Caen, as well as Barfleur, the latter on the northeastern tip of the Le Havre peninsula near St. Vaast La Hougue where a tremendous artillery duel had erupted.

Heavy infantry fighting was reported between Caen and Trouville.

A detailed map shows the approximate locations of the beaches in relation to French towns: Utah being slightly north of Isigny, Omaha being just to the east of Isigny, Gold being opposite Bayeux, Juno opposite Caen, and Sword in the area of Deauville.

Associated Press reporter Gladwyn Hill provides a firsthand account of the invasion from inside the cockpit of one of the supporting aircraft.

Another inside page provides the overall command structure for the various Allied forces.

The American First Army, under the command of General Omar Bradley, consisted of 73,000 men, including 15,600 airborne troops.

The British Second Army, under the command of General Sir Miles Dempsey, included 83,000 men, 22,000 of whom were French, Australian, and Canadian. General Sir Bernard Montgomery was in overall command of British ground troops.

Casualties for the Allies in the landings were reported to be a fraction of those expected by Allied Headquarters. Not yet reported, they numbered about 10,000 total, of whom 6,603 were American, including 2,499 killed, about 3.5% of the total American forces; 2,700 British, of whom 1,556 were killed; and 1,074 Canadian, of whom 359 were killed.

The British suffered about a thousand casualties on each of Gold and Sword beaches, with the remaining 700 among the airborne troops. The Canadian losses all occurred at Juno Beach. Utah Beach accounted for only 197 American casualties.

The bulk of the casualties, some 4,000, took place at Omaha Beach, the most heavily defended of the landing areas, in part because Allied artillery fire had not reached all of the German guns in advance of the landings, in another part because of the heavy Allied troop concentration, and in another part because of the high bluffs affording German pillboxes greater coign of vantage to the wide expanse of beach. Precise figures of casualties at Omaha have never been compiled. About the same number died as at Pearl Harbor, 2,341 military personnel.

The relative deployment coincided with Prime Minister Churchill's demands at Tehran and earlier that the Americans bear the brunt of the infantry advance to spare the trained contingents of British troops to act as reinforcements, protect the home defenses in Britain, and to spare the youth of Britain, a generation of which had been depleted by World War I.

German casualties are only vaguely estimated at between 4,000 and 9,000.

President Roosevelt addressed the nation by radio on the evening of this date, delivering a common prayer. Prime Minister Churchill addressed Commons.

Another inside page continues the front page story containing the draft of the President's prayer, written the previous night in conjunction with the White House chaplain while the invasion transpired, as well as more of the story on General Eisenhower's confident view of the invasion as expressed to the press.

General George C. Marshall, commander of the American Army, had maintained normal office hours at the Pentagon on Monday and departed, per the usual course, at 5:30, then spending time at the Soviet Embassy being decorated by Soviet Ambassador Andrei Gromyko with the Order of the Suvorov First Class, the highest Russian military honor. He stated next day that he had done all of his work before the invasion.

Secretary of War Stimson had also maintained his usual Pentagon hours, even though the inter-workings of the labyrinthine building were beehive busy during the night.

The Russians greeted the news of the invasion with gladness as the long-awaited second front was now fully opened. It was reported that Russian troops were massing on the Eastern front in Poland for the inception of the final push toward Germany from that direction.

In Vichy, Marshal Henri Petain, true to form since June, 1940, encouraged, via Paris radio, the French to obey their Nazi masters and eschew Allied invitations to join their cause and participate in the underground.

The Free French out of Algiers hailed the attacks as the beginning of the liberation of France and urged the underground to action to assist the Allies. General Eisenhower, in his general announcement of the invasion, urged the underground to be patient in their actions, that premature activity would only unnecessarily endanger themselves and thereby compromise their effectiveness in aid of the Allied advance. General De Gaulle was reported to be in England.

It was indicated contemporaneously that the invasion had been originally set for Monday, but was delayed by severe Channel weather for one day.

We note that the daily Dover weather report, which The News had carried during May under the heading "Invasion Weather", suddenly stopped appearing on the front page on May 31. Its appearance on an inside page this date suggests that it may have continued in the interim. Regardless, Dover weather likely was disseminated to American newspapers as a ploy by the Office of War Information to fool Nazi spies into communicating the belief that the invasion would take place across the Dover Strait at Calais, the area receiving the bulk of the bombing along the French coast during the previous five months, stepped up during the four days preceding the invasion. Practically none of the bombing in recent months had focused on the Normandy coast between Cherbourg and Le Havre.

On another inside page, Hal Boyle, moved off the front page by the extended coverage of the invasion, tells of the factors involved in such an enormous undertaking to supply and transport such a huge force of men. He had accompanied the Allied invasion at Morocco in November, 1942 and so had gleaned a good stock of information firsthand on this complex endeavor. Photographs on the page of earlier operations aid the reader's understanding of that process. Mr. Boyle was presently accompanying the invasion of France.

The page also reports that Berlin radio contended that Berlin remained calm in the face of the news of invasion. But, according to London reports, a large amount of chatter on the airwaves indicated that the French coastal defenses had been caught napping.

Another

inside page reports of Londoners being happy that the attack had finally begun. One housewife with a husband in the fire brigade and a son in the invasion forces stated that she almost wished the Germans would attack London, that it would make her feel better.As we gave you this morning, historically on time, an Extra Edition of The News appeared, with an inside page, assembled by managing editor Brodie Griffith, constructed from scratch at the first hint of the news of the invasion at 3:32 a.m., as air raid sirens broke the still of Charlotte's night at 4:03, followed by ringing of the church bells summoning the populace to prayer. The Extra was out on the streets by 7:00.

Two Charlotte men were reported walking side by side down College Street, both carrying the Extra and reading it. Becoming aware of one another, they exchanged, "Mornin'." Each then said to the other that he had a son in the fight and continued walking--in silence.

And, should you have performed well your studies, you may check in with the desk clerk at the Taft Hotel in New York City on 7th Avenue, where those who compare, perhaps also do declare, Tarry at the Taft

On the editorial page, "Victory and Death" solemnizes the occasion of the Normandy landings, that the day long awaited had finally arrived, would inexorably lead to the downfall of Hitler and destruction of the Nazi Party, even if the Allied forces still had through long and harsh valleys yet to tread.

"For these young men, for ourselves, and for generations to come, we must keep the grim pact of this day, written in blood."

The remainder of the page was drafted prior to the news of the invasion and is redundant of previous editorials and so you may read it for yourself. We make note of the piece by Marquis Childs, regarding the proposal made since the previous fall by Tennessee Representative

Dorothy Thompson observes the future of labor and social security in the country, viewed through the eyes of Labor Secretary Frances Perkins speaking before the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in Boston.

Samuel Grafton relates of the Political Action Committee of the CIO and its future impact on political life in the United States.

Drew Pearson discusses: Mrs. Roosevelt's dislike for Mr. Churchill, a tale which has its humors, the vision of the Prime Minister padding up and down the hallways of the White House at all hours of the night in his slippers and gold-and-red silk kimono, keeping the President awake to the annoyance of the First Lady; the lack of promotion and commendations for pilots; and the reported improprieties by tire dealers illegally retaining ration coupons to enable acquisition of more tires than normal government allotment would allow.

As indicated, a poignant address was provided that night by President Roosevelt, one of his last to the nation. It is the most eloquent summary and editorial of the day.

May such a day and such an hour never again become necessary.

![]()

Labeo and Flavius, set our battles on:

'Tis three o'clock; and, Romans, yet ere night

We shall try fortune in a second fight.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()