![]()

The Charlotte News

Monday, May 31, 1943

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page announces the final fall of Attu, a fait accompli for the previous ten days, to the Americans after twenty days of fighting. At the end, a doomed thrust by the last of the Japanese contingent out of the Chichagof Valley was cut to pieces, leaving only 29 prisoners captured out of an initial force estimated at 2,900.

Now, the Allies' control of Amchitka to the east of Kiska and Attu to its west meant that a blockade could effectively be imposed on the last Japanese hold in the Aleutians. By the end of July, Kiska would be evacuated, an empty island by the time the American forces landed on August 14. The Pacific Northwest was no longer threatened by the Japanese. Strategic thinking also had it that the Aleutians opened up possibilities to the Allies to conduct raids into the Kuriles from which might be effected air raids on Japan. That strategy, however, would never prove realistically achievable enough to implement.

Reports from Berlin predicted that June 22, presumably because of its coincidence with the date two years earlier of the German invasion of Russia, was the target date for the Allied invasion of the Continent. Probably suggested publicly for the purpose of delaying the action to afford a longer period of preparation of defenses of the Festung Europa, the date suggested was only seventeen days early, as the invasion of Sicily would begin during the night of July 9.

Three days after the attack at Livorno and Foggia, another major U.S. bombing raid of Flying Fortresses and Liberators struck Italy on Sunday, a hundred B-17's hitting Naples and fifty B-24 Liberators again bombing Foggia.

The Russians announced that they had downed 456 Luftwaffe planes during the previous week, losing 118 of their own; fully 2,069 enemy planes had been bagged during May.

General Charles De Gaulle and General Henri Giraud had finally agreed, at the urging of the Americans and British, to form a joint governing executive committee for France, with each holding joint leadership over the committee. De Gaulle selected two of the members, Giraud another two, with both jointly appointing a fifth member, and two positions held in reserve. The seat of government would be Algiers until such time as France could be liberated from German control.

A series of abstracts from They Call It Pacific, by reporter Clark Lee, begins this date in The News and continues on the inside page. The first chapter begins in Japanese-occupied Shanghai on November 14, 1941 and tells initially of Mr. Lee's encounter with Sgt. Matsui of the Japanese Army, a native of Southern California who could not find acceptance in the United States and so defected to Japan, joined the Army. He had been instructed by a colonel, who had taken a liking to Mr. Lee as a reporter, to warn him that internment camps were going to be the repository for all Americans and British in Shanghai when war came, that all ships bound for the east were scarce, that the last two presently in port might well be the last before war erupted.

Sgt. Matsui told Mr. Lee that special envoy Saburo Kurusu had been sent to the U.S. to take a special message to Secretary of State Cordell Hull, that Japan must be left alone with its present conquests in Manchukuo in southern China, Hainan Island in the South China Sea and French Indochina. Rejection of the ultimatum surely meant war.

And Mr. Lee already knew that such an ultimatum would not be acceptable to the United States. He also knew that Japan, without trade with the U.S. since latter July, at Japanís occupation of Indochina, needed oil, iron, manganese, tungsten, tin, chrome, nickel, and rubber to continue to wage war and maintain its empire interests, each, save iron, obtainable from the Malay Peninsula and the Dutch East Indies. Iron was available from Shansi Province in north China.

Armed with the valuable tip to escape while he could, Mr. Lee sought passage on the next ship out, the Tjibadak, bound for Manila where he could catch a ride on the President Coolidge, so that he might return to the United States for the first time in over five years.

An American military attaché to Tokyo explained that Japan was in the process of sending the bulk of its 2.5 million men under arms, of whom 1.6 million were combat troops, south toward Hainan or Saigon. Only about 250,000 troops were stationed in China. The remainder were being mobilized southward. War appeared imminent. That, the press already understood. They had burned their incriminating stories on Japan's war effort in China during September so that they would not be persecuted if caught by the Japanese; the stories had been smuggled out, away from the prying eyes of stern Japanese censors, and published under Manila or Hong Kong datelines. Shanghai was hot; it was time to get out while the getting was good.

The obvious question is always then, if so many knew that war was imminent, as most of the American press, government and military of the day did, as was evident in the press accounts stateside during the fall of 1941, why were they not prepared at Pearl Harbor?

The answer is actually fairly simple: no one, including the command structure at Pearl Harbor, anticipated the Japanese willingness to risk the bulk of its Combined Fleet to martial enough planes in force for an air attack 4,000 miles from its base of operations.

At the time, the Japanese air prowess was, in military circles, a standing joke. The movement south of so many troops and a Naval Task Force with it had served as an adequate distraction to suggest an attack on the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, and the Malay Peninsula--each of which of course did in fact become objects of attack shortly after the attack at Pearl Harbor began. The threat was deemed high in those areas, low, and in readiness to deploy to protect those areas, at Pearl Harbor.

The Pacific Ocean is a vast place and in 1941 was not susceptible to wide patrol; radar was primitive and short range. The Japanese employed a northern route, seldom traveled by merchant ships, never patrolled by military aircraft. Moreover, the travel was protected by fog. No military intelligence had maintained track of the Japanese Fleet congregating northward in the Kurile Islands, the Fleet's point of departure from Japanese home waters, on the assumption that the ships had gone there for exercises. Radio silence had been maintained during the voyage; thus, the fleet could not be triangulated for location and was not detected, at least not by any credible sources which have ever surfaced.

The Oil Can route was simply not only never detected; it was never conceived to be anything but a fool's game to attempt. The whole operation was simply so impracticable as to be an absurdity of logic to put into practice. No one thought the Japanese capable of it or, if so, willing to risk the bulk of their entire fleet on one such bold move.

That is how it was accomplished; that is how the fate of the Japanese Empire became writ in large and how it was brought to its knees finally by the deployment of the world's first atomic bombs.

For sneak thieves who persist, there is reserved a special form of punishment. Imperial Japan was provided it, and deservedly. It was an act not of war, but an unprovoked act of criminality which eclipsed even Hitler's invasions of Poland and Russia for sneakiness and back-stabbing.

On the editorial page, "Turning Tide" examines the fateful change in the European war during the fall, winter, and early spring of 1942-43, the victory at Stalingrad in late January, followed by the victory in Tunisia in the first week of May, after the Tunisian Campaign appeared in grave doubt, or at least in stalemate, in late February after the debacle of Kasserine Pass. The piece compares the turning of the tide to that in 1918 after the Second Battle of the Marne left the German Army for intents defeated as of August 8, 1918. From that point forward, the end was a fait accompli, as General von Ludendorff reported to his superiors in September. It would come at 11:00 a.m. on November 11 with the Armistice signed in the railroad car at Compèigne.

The editorial predicts that the cresting tide would soon swamp the Wehrmacht in precisely the same fashion, just as Sam Grafton had stated on Friday that the avalanche was roaring down the mountain toward Der Fuehrer, with the Russians having swept the path for its more rapid advance.

It would be so, but it would still take longer than a mere three months as in 1918. For this time, there would be no armistice. The only term of surrender would be unconditional. That would take longer to effect. The Allies this time were not planning to have to return to Europe in 1968 to fight another war against a Fourth Reich.

"Lord Jim" reposits full confidence in the abilities of James Byrnes to carry into practice with equanimity and competence his vaunted role of War Mobilization Board chair, with responsibility for coordinating all government agencies with the military to effect a smooth-running operation of the war and to create and implement strategy in the war at the direction of the President.

"Little Attu" recognizes that the victory on Attu would not go down in the history books as much, but nevertheless was a start from the north sending the Japanese back to their home waters, securing the Pacific Northwest and Alaska from Japanese attack, as the Japanese position on Kiska could now not long be sustained, cut off from supplies.

Raymond Clapper once again looks at the division in Swedish discontent regarding the traffic of German soldiers across Sweden to and from Norway, the press, labor, and ruling Social Democratic Party, along with the bulk of the citizenry, all solidly opposed to it, the entrenched bureaucracy, especially the Foreign Office, continuing in a timid mold, fearful that stepping on Nazi toes would bring down upon Sweden's neutral head some form of occupation to enforce the movement.

Mr. Clapper points out that while in mid-1940, the policy might have been sensible to avoid occupation as with its neighbors, now Sweden had little practical fear as Germany was in a defensive posture and could scarcely afford to devote the resources required for an occupation force of Sweden with so little in spoils to be gained and so much to be ventured, already stretched far too thin across Europe, the Wehrmacht's primary concerns now being the southern Russian front and the Mediterranean and Channel coasts. For without the oilfields of the Caucasus, of Baku, the ability even to wage a defensive war on the Central Continent was limited in time. And, the Nazi had his back to the wall at Novorossisk, threatened with expulsion into the Black Sea, on the other side of the Caucasus from Baku.

Samuel Grafton--having examined on Saturday the idée fixe of the Republicans and anti-New Deal Democrats in Congress with respect to bureaucracy as an abstraction, such that the Farm Security Administration, beneficial and efficient in its provision of low interest rate loans to the farmer, had nevertheless been with a dash smashed out of existence, the Congress never thinking of the actual farmers whose lives and efficient farming operations, in substantial support of the war effort, had been made with the same dash substantially more complex and harder to maintain--now turned his attention to comparing New Deal liberalism which supposedly had created the anti-democratic bureaucracy, of which the anti-bureaucrats complained with such hot breath, to that in Britain under a Conservative Government. He finds that Britain had even more bureaucracy, far more antithetical to democratic notions, than did the United States.

So, he concludes, the anti-New Deal carping notwithstanding, there was no liberal conspiracy to form a giant web-work of bureaucratic agencies slowly to convert the country to socialism, any more than there was a conservative conspiracy in Great Britain to do likewise. Churchill's attitude domestically was to preserve the status quo. Both countries were responding to emergency conditions of economy and war, forcing in combination the unprecedented strictures, to fight Fascism and Nazism in Europe and feudalism in the Pacific.

And, Mrs. Loy Beam writes again on the subject of Hoskins and Thomasboro.

Mrs. Loy Beam now signs her letter from Thomasboro. We did a double-take, as she now takes the attitude that she was not meaning in her previous letter of May 20, to insult the people of Hoskins, while maintaining her pride in Thomasboro.

Well, you go back, read her first letter, and figure it out for yourself.

Mrs. Loy Beam was either putting us on or completely schizoid or had moved herself and the other bright Beams across the creek and the P. & N. Railroad during the interim eleven days.

We conclude that the whole Hoskins-Thomasboro flap being hauled out was no more than a ruse by some people trying to pull one over on the gullible city folk.

Ack, ack, ack. You see what happens, small town rustican, when you seek to fool the city populace.

Mind your manners. You're liable to wind up getting gobbled up.

Speaking of which--though, in so doing, we mean not to deign to cast any equivalent aspersions politically on the good patriots in both Hoskins and Thomasboro of 1943--as to the flak hurled at the President today for having spoken, albeit pre-empted by a thunderstorm, at the National Cemetery in Elwood, Illinois rather than at Arlington, you have to be putting us on, Limbecks.

Even your fearless Leader, in 1983, didn't attend Memorial Day ceremonies at all, because of a G-7 Summit meeting.

Why don't you study a little history for a change rather than opening your mouths, as if divinely inspired, without the necessity of even the scantest backing fact, simply because some of your number proclaim to be "veterans"? We ask: on whose side were you fighting? That of the Constitution, or some other side?

As we pointed out last year, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles delivered the speech at Arlington on Memorial Day, 1942, that which one might dub the "new frontier" speech; President Roosevelt remained across the Potomac.

John F. Kennedy, a veteran and war hero in his own right, never once spoke at Arlington on Memorial Day, only once spoke there, in 1961, on Veterans Day, while making a brief appearance on Veterans Day, 1963, laying the wreath at the Tomb and attending, up to the point of the benediction, the ceremony in the Amphitheater--yet never speaking a word in the process.

Sometimes, the sounds of silence are better yielding of the fruit of democracy--that for which, presumptively, every true veteran fights, whether merely acting as a citizen or within the context of the military, in defense of our Constitution--, than inauspicious wind, given form by overly large windbags.

No doubt, tomorrow, these talk-radio geniuses, who regularly cook up and promulgate among their listeners this sort of stuff, will be proclaiming some supernatural portent associated with the thunderstorm at Elwood, cutting off the President's speech, that their direct pipeline to the deity manifested it. In anticipation of which, we remind their highnesses that Hitler and Tojo, not to mention Macbeth, also thought the weather gods to be in their corner.

And they appeared to be, for awhile.

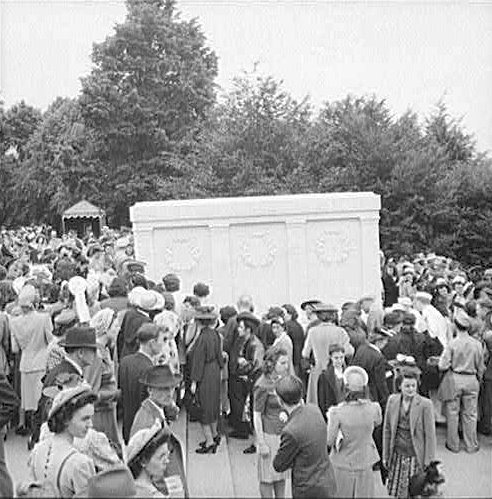

![]()

Memorial Day, Arlington, Saturday, May 29, 1943

They insisted on democracy; they won the War

![]()

![]()

![]()