![]()

The Charlotte News

Saturday, January 30, 1943

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page declines offer of any positive bearing from which the Third Reich might take renewed confidence on this the tenth anniversary of its coming to power in Germany. Things were anything but good on all fronts, in North Africa, in Russia, in Berlin itself, where more bombs fell in the first daylight raid on the city by British bombers, the ultimate insult to the Anglophobic Hun, after American four-motors had already begun during the week inflicting daylight misery from the air. The attack was carried out by light Mosquito planes which attacked at 11:00 a.m., delaying by an hour the beginning of German anniversary festivities for 10,000 Nazis gathered at the Sports Palast.

Hitler, the consummate coward, stayed in his bunker as his proxies, Goebbels and Goering, addressed the crowd, reading Hitler's prepared proclamation. It went, more or less: "Blah, blah, blah, blah, blahahaahablababababa-ha-haba-blah. Blah-blah-hah-hah. Blah, blah, blah, blahblahblah… Sieg Heil!"

Sample, after translation: "The blows we may suffer are nothing in comparison to what they would be if barbarism swept across Europe."

Then, Herr Doktor Goebbels was reported to have set aside his hookah for a few minutes to rest his overworked mind. According to observers, his visage resembled a smoking mirror.

Heard in the background was a disembodied chorus of voices, to the confusion of all present as to origin, singing in English: "Don't you feel small? It happens to us all."At the end, all in attendance were taken out back and shot per the usual course, to leave no witnesses to the Big Lie.

It was also President Roosevelt's 61st birthday, as celebrated on the front page by the photo montage of his life and public career. He would have but two more to celebrate.

The editorial column first remarks on the Congressional accounting of Lend-Lease to insure, unlike the unpaid debts of World War I, that foreign nations receiving aid would reimburse reasonably in kind.

Recent reports had stressed that Britain was paying its fair share in manufactured goods from British factories to bolster the war effort, made from raw materials shipped from the United States.

The editorial finds no fault in the congressional oversight to insure maintenance of healthy efficiency in the distribution of aid.

"The Mirror" compares Robert McCormick's recent editorials in the Chicago Tribune, anent the Casablanca Conference as one grand show by FDR and Churchill, to the very similar rhetoric being disseminated by the stooge press in Berlin. The piece deduces from this similarity in viewpoint that the next Conference, the scène à faire, ought be exclusively attended therefore by Mr. McCormick and Der Fuehrer.

"No Cheers" cautions against over-optimism from the announcement of 1,258 American casualties to date in the Tunisian campaign, only 211 of whom were listed as killed, most in the initial landings November 8.

Yet lay ahead, astutely forecasted Mr. Davis, a high death toll in wresting from Rommel his tenacious hold on Bizerte and Tunis, to which reinforcements and supplies could be regularly sent the hundred air miles from Sicily.

Indeed, by the end of the campaign in early May, the casualty figures would catapult steeply, especially after the tremendous losses at Kasserine Pass in the latter days of February, where 10,000 Allied casualties resulted, 6,500 of whom were American.

American casualties for the entire Tunisian campaign were 2,715 killed, 8,978 wounded, 6,528 missing; the British numbered 6,233 killed, 21,528 wounded, 10,599 missing; the Free French, 2,156 killed, 10,276 wounded, 7,007 missing. Most of these losses occurred during the months of February through April, 1943.

Dark days lay ahead before any further sliver of light could be shed on the Nazi in his endless tunnel vision, endless shadows and hazy fog, trained and brainwashed not to think, not to emote, to view human compassion as but a feminine trait. Not until Hitler and Goebbels had beat the hangman by blowing out their own brains would any light again enter Germany.

In the last chapter of They Were Expendable by William L. White, Kelly relates his initially frustrated efforts to obtain a plane to Australia. He shares quarters with a career Navy captain of 30 years who was determinedly pessimistic about their prospects to get catch the ride to Melbourne. No planes, no gas, all hopes are minimal to non-existent.

For six days Kelly heard the depressing refrain and became increasingly morose with each passing day when no plane arrived.

On the night of April 27, he listened to a shortwave broadcast out of San Francisco about his own mission to sink the cruiser and about the general state of things in the Philippines. It all sounded so rosy that it made Kelly mad. The true picture, he knew, was anything but the way it was being described to listeners to buoy morale. Even the report on his own mission was incomplete, stating that he had been run aground by enemy strafing. What would his family think?

He went to bed angry that night, knowing that the truth was being obfuscated with lies, the truth being that they had been forced to fight until expended, to try to delay for as long as possible being overrun by the Japanese fighting force, of far superior equipment and numbers of trained and experienced personnel. Even of that modest mission, he believed, they had achieved nothing greater than abject failure.

History of course would prove this unduly self-effacing assessment untrue, as the entire effort was part of a larger plan to winnow the best, most experienced front line Japanese forces by defensive stands to enable the Allied counter-offensives of the summer on New Guinea and Guadalcanal after the Japanese air force, army, and navy were depleted of their best ships, especially the decimation of their carrier force both in ships and planes, and most experienced pilots and infantry who had fought for five years in China. Once down to their second line troops, parity of experience had set in with a vengeance and now the earlier sacrifices of the Expendables was paying off a year later.

But Kelly did not understand that nine months earlier.

The following morning, he received a call from the colonel with whom he was at odds over the carabao mission. An aviator without an airplane to fly had been collared into rounding up the water buffalo, successfully having herded 39 of the 50. The colonel therefore wanted Kelly to reconnoiter along the trail to Lake Lanao to insure that all was clear and fit for the tramping herd of "milk cows".

Kelly was preparing, without enthusiasm, to follow his orders when, fortuitously, General Sharp summoned him to the airfield to catch his plane to Australia.

When he told his bunk-sharing Navy career captain of his good fortune, the elder man wished Kelly luck, but with tears in his eyes, understanding that it was youthful skill the Navy now needed, not old career men. He was resigned to his fate as an expendable, consigned, as so many obsolete spare parts for planes and ships of World War I no longer of use, to fight it out in some trench until the last bearing had fallen off his soul.

Kelly made his way to the airstrip where they waited, a hundred or so hoping for one of thirty spots on the plane. Or, maybe there would be, by chance, two or three planes and all would get to go home.

Kelly also ran into "Ohio", one of his fellow patients, along with "Texas", mentioned earlier in the story from his days during February at the hospital on Corregidor. Ohio had already missed one earlier roll call at which he would have obtained an outbound seat; now he hoped for the best. He had flown to Corregidor twice in the Beechcraft to deliver medical supplies, but only touched down briefly in the dark leaving no opportunity to see any of the nurses. No, he told Kelly, no sign of Peggy.

Suddenly, all conversation broke off as they heard the plane arriving out of the moonlit night. Tension rose as only one searchlight hit the runway, the thirty with the low numbers hoping that it wouldn't crash as it attempted the perilous landing.

Akers and Cox had been assigned numbers in the first 30 along with Kelly, but they were nowhere to be seen at 10:30 when the roll was called. Their numbers therefore were assigned to an Army tank major and an Air Corps captain.

Then, at 10:35, Akers and Cox suddenly came running into view and the captain and major had to give up their seats to await another ride.

General Sharp came by to wish Kelly farewell, telling him to ask General MacArthur for a hundred thousand men and a tanker full of gas to give him the means to hold off the enemy indefinitely and even start recouping the lost territory in the islands. The general, however, knew the score and understood that his request was little more than a grim jest. He, like the Navy captain, understood well that all those left behind were expendable. "We are ready for it," he said, "and I think they will see that we will meet it squarely when it comes."

The men handed their .45-cailber pistols over to the soldiers left behind and boarded the plane to shove off to Melbourne.

Back in the spring sunshine of Newport, someone asked Kelly what had happened to Peggy. He reported that three seaplanes had been dispatched to Corregidor to rescue the medical personnel. One had crashed before landing but the other two picked up passengers and made it back to Lake Lanao for refueling as General Sharp and his band of Army regulars and native Moros held off the Japanese. One of the two planes got safely away and made it to Melbourne. The other, however, the one he had heard was carrying Peggy, crashed on take-off. He didn’t know where she was.

As the plane in which Kelly, Akers, and Cox were riding took off, he saw the moonlight slice across the water, much as it had at Manila Bay when he was courting Peggy just a few weeks past, now seeming as if in a dream, only seconds away. She had said then, as he heard it again clearly in the night air, "It's been awfully nice, hasn’t it?"

![]()

"Perhaps the wind wails so in winter for the summers dead..."

Robert Bolling Kelly, a graduate of Annapolis in 1935, went on to receive both the Silver Star and the Gold Star, the latter for "conspicuous galantry and intrepidity" as part of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 9, of which he subsequently became commanding officer as a Lieutenant Commander, operating during 1943 in the Solomons, in the area of Bougainville and New Georgia.

The Gold Star citation read in part:

Displaying expert seamanship and superb courage, Commander Kelly personally led groups of his boats into combat against hostile barges, aircraft and shipping. Despite frequent bombing and fierce gunfire from barges and shore batteries, he daringly attacked the enemy, inflicting heavy damage and casualties. During the New Georgia Campaign, when a boat under his command was in danger of capture by the Japanese, he swam out to the threatened ship in daylight to remove confidential matter in order to prevent its falling into enemy hands and, although sighted and fired upon by a hostile shore battery, succeeded in carrying out his perilous mission. Commander Kelly's heroic leadership and indomitable fighting spirit reflect great credit upon himself, his command and the United States Naval Service.

As indicated, he received the Navy Cross for his sinking the cruiser on the night of April 8-9, 1942.

That citation read:

Despite extremely heavy shell fire opposition, and the fact that the cruiser was screened by four enemy destroyers, the PT-34 closed to three-hundred yard range and made two successful torpedo hits on the enemy cruiser, finally sinking her. Then, on the following morning in a narrow channel of Cebu Harbor, with three guns of the PT-34 out of action and a hole six feet across blown through her, Lieutenant Kelly maneuvered to save his boat from further direct hits from four attacking enemy dive bombers. He maintained fire against the enemy until all of his remaining guns were out of action, and with five of his crew of six killed or wounded, he beached his boat and, under continual strafing from the enemy, directed the removal of the wounded to a place of safety.

His Silver Star was awarded for his part in transporting General MacArthur and his entourage from Manila Bay to Mindanao on March 11-12, 1942.

Eventually being promoted to Commander, he survived the war and lived to age 75, passing away in Columbia, Md. in late January, 1989.

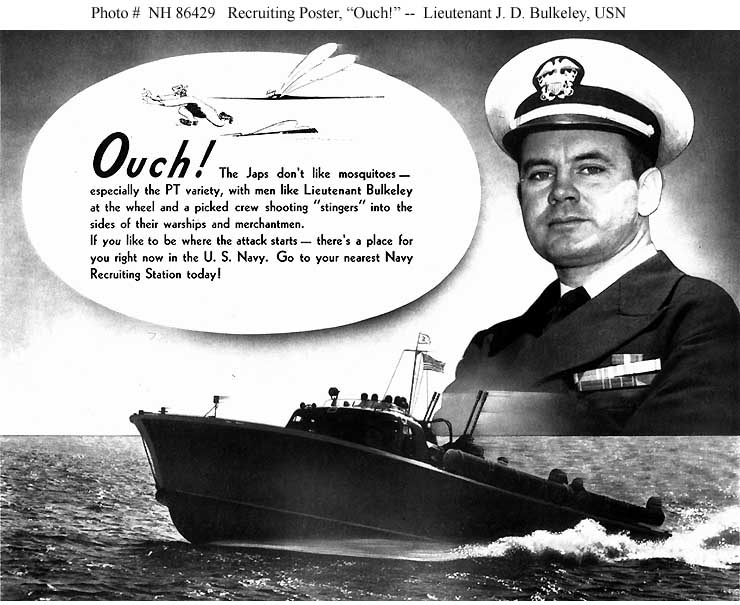

John Bulkeley, who had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1933, went on to participate in D-Day, leading a squadron of Motor Torpedo Boats running interference and protecting landing transports and minesweepers. A career Navy man, he eventually rose to the rank of Rear Admiral, promoted by President Kennedy to that rank in 1961, serving as commander of Guantanamo during both the Bay of Pigs operation and the Cuban Missile Crisis. He retired from active service as Vice-Admiral and passed away in Silver Spring, Md. on April 6, 1996 at the age of 84.

Decorated numerous times throughout his distinguished career, he had already been awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions throughout the four months of operations in the Philippines, from December 7 through April 15.

That citation read in part:

The remarkable achievement of Lieutenant Commander Bulkeley's command in damaging or destroying a notable number of Japanese enemy planes, surface combatant and merchant ships, and in dispersing landing parties and land-based enemy forces during the four months and eight days of operation without benefit of repairs, overhaul, or maintenance facilities for his squadron, is believed to be without precedent in this type of warfare. His dynamic forcefulness and daring in offensive action, his brilliantly planned and skillfully executed attacks, supplemented by a unique resourcefulness and ingenuity, characterize him as an outstanding leader of men and a gallant and intrepid seaman. These qualities coupled with a complete disregard for his own personal safety reflect great credit upon him and the Naval Service.

He also received two Distinguished Service Crosses, a Navy Cross, and the MacArthur awarded Silver Star for service during January through April 8-9, 1942.

As earlier indicated, "Peggy", whose real name was Beulah Greenwalt, Army lieutenant, served out the war in a detention facility in Manila, protecting the regimental flag from Bataan by wearing it as a shawl to fool her Japanese captors.

She was freed in early February, 1945 at the liberation by the Allies of Manila and was home in Missouri with her ailing mother by the time the Japanese evacuated the Philippines March 3. She passed away in January, 1993 at age 81 in Palo Alto, California.

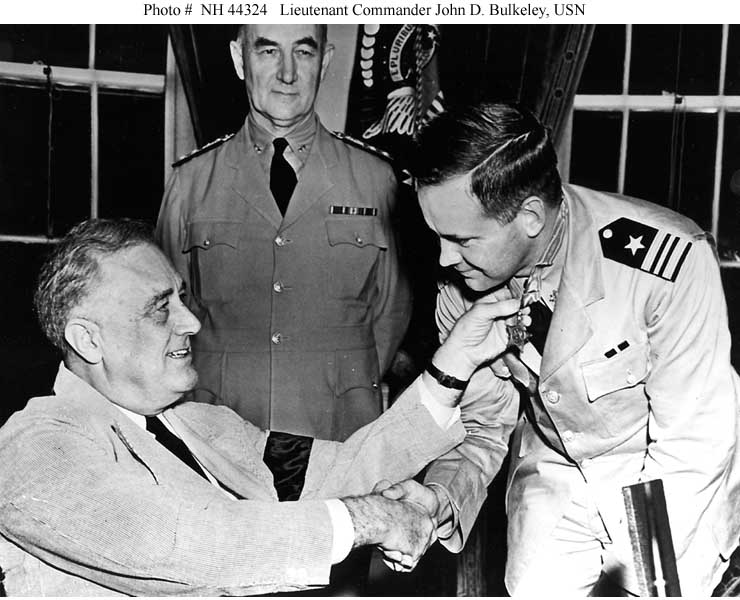

The following two photographs are of John Bulkeley, one aboard a PT-boat in 1942 and the second, receiving the Medal of Honor in July, 1942 from FDR. (Another photo from this presentation appeared in The News August 6.) The third image is a recruiting poster, also from 1942.

The book, published by Harcourt, was a bestseller in fall 1942 and into 1943, was reviewed favorably in Time, which mentions incidentally that the Navy changed the title from "They Were Expendible", and was 225 pages in length. The abstract therefore printed in The News in 24 installments appearing between January 4 and this date was something less than half of the published volume.

As a postscript, we note that on this past Monday night, we watched for the first time the December, 1945 movie version of the book, John Wayne playing the role of Lieutenant Kelly, Donna Reed as Peggy, and Robert Montgomery as Lieutenant Bulkeley, albeit each represented under a pseudonym. Before seeing the John Ford directed film, we drafted the note of January 15 which referenced the "message to Garcia" in relation to the three dollars charged by the pineapple plantation manager to deliver messages from Corregidor to Manila. The book abstract did not make the reference to the Elbert Hubbard piece. That becomes interesting in relation to a scene early in the movie in which Kelly sarcastically expresses his frustration at the squadron, anxious to engage battle with the Japanese, being instead assigned by the Army to the thankless task of ferrying messages to and from Manila; when subsequently summoned before the admiral for an urgent matter, Kelly says to Bulkeley, "Probably wants us to carry a message to Garcia."

Well, Pilgrim, make of it what you will, but we never saw the movie or any part of it before last Monday night, January 25. We wrote the reference in the note ten days before that.

The tomcat, incidentally, in the movie version was not eaten. It was probably considered gratuitous violence.

There was also no appearance by General Tojo.

And, if you would like to catch the movie, it is scheduled, as it so happens, to run on Turner Classic Movies, February 17, 2010 at 3:30 p.m. Be there.

![]()

![]()

![]()