![]()

The Charlotte News

Tuesday, September 8, 1942

FIVE EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The front page reports of Wendell Willkieís visit to Egypt with an indication that all now was going well, Rommelís invaluable tank forces having been decimated by the recent British push-back to the west, his tanks down from 290 to 190. Such a report came as welcome news when only a bit over two months earlier Alexandria appeared at peril of falling, and with it, all of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

At the same time, the Prime Minister appeared to confirm to Parliament the same picture, an accurate picture, that Rommel now was on the run, this time for good, while announcing at the same time that a second front was soon to begin. The hints as to where it would be were mixed, a suggestion being that the Dieppe commando raid was signal of a front to be opened on the French coast.

Immediately to the right of that piece appears the report that the President had informed the press of preparations underway for a second front in Europe, the decision for which having been entered in July.

Put the two latter pieces together and just where the Allied front would be opened remained subject to guess, ranging over quite a vast area, anywhere from Norway to North Africa and all points in between, notwithstanding perfect hindsight suggesting North Africa, then Sicily.

But, to Hitler and his information monitors, were the indications at all accurate? Talk in the press, talk by the Allied commanders, talk by Administration spokespersons, had been ongoing since early summer re the opening any day of that second front to relieve the Russians, indeed had even proceeded during late April and May. Still, other than the bombing raids over Europe and this recent counter-thrust from the stand of the Allies taken in early July at El Alamein, no second front had been opened, despite the unrelenting bad news from the Don Bend and in the Caucasus, down to within practical earshot of Stalingrad to the north and Grozny to the south, the Nazis seeking the while the railhead down the coast to the critical Caspian Sea oil depot of Baku.

Hitler could have gambled again, sought to shore up Rommelís forces through the heavily contested Mediterranean, to the bitter end, withdrawing for this critical last period in advance of Russian winter the much needed forces in the Caucasus, continually being depleted by Semeon Timoshenkoís resolute defenders, and thus in need of continual reinforcement.

He could have further shorn the sheep of the Russian front by removing some of his pilots and infantry back to the shores of France. But his good news from that front on the resistance to the Dieppe raid no doubt reinforced his continuing delusion that the French coast was quite secure for the nonce from Allied invasion, from the landing of ships and troops in profusion.

Thus, he chose to fight on in Russia, chasing down the Kuban, forcing the Don Bend, seeking Stalingrad, and seeking Grozny, down the rabbit hole, deeper and deeper, into the depths of oily Hell.

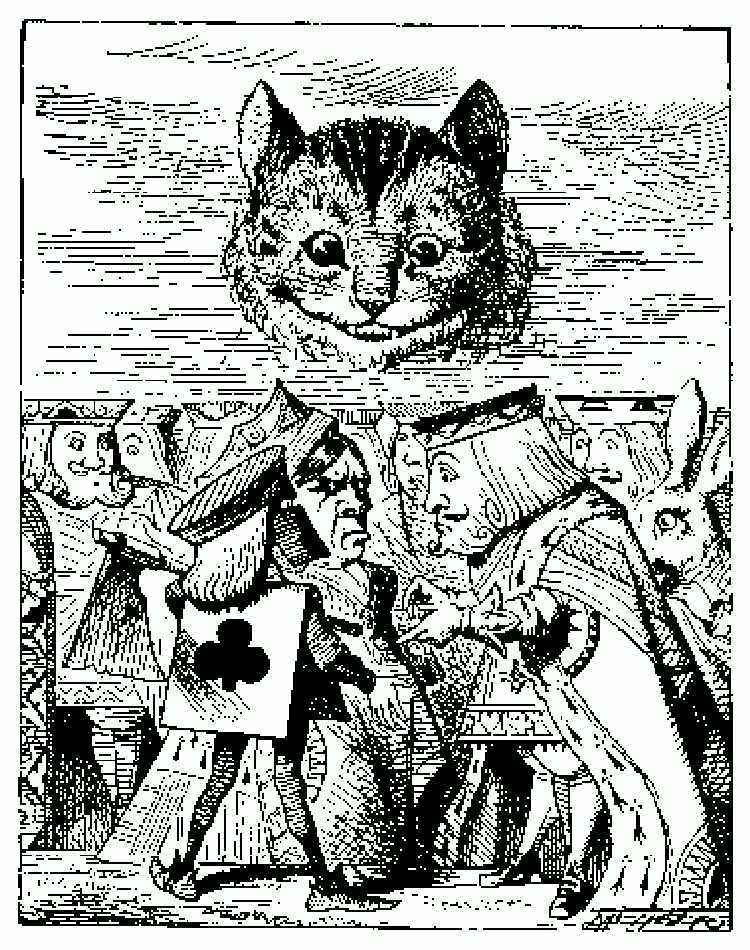

--Illustration by John Tenniel, England, 1865

In Asbury Park, New Jersey, some "hepcat" named Patsy paid the price of being too hep, says the little piece, straining his left shoulder in the movement doing some kind of hepcat swing, apparently using his left arm as the axle rotating around which his shoulder joint became the grease.

Even in 1942, it would appear, it didnít pay to be too hep.

But donít blame Patsy.

For he was just a patsy to the Wurlitzer, ace-spinning rhythms of the fire in jukes.

In China, Chiang Kai-Shek had appointed Dr. Hu to the new post of high adviser to the cabinet.

Whether, however, the new position was higher than a mile high is not reported.

Also not reported is just who Shih was.

At least Dr. Hu, though, unlike Togo in Japan, was, we are inclined to opine, no Patsy.

The editorial page begins with the sad story of a mother who shot her young daughter and then killed herself. The piece puzzles over the matter and offers sorrow and compassion.

Of course, by this point in time, with the dayís headlines, nearly everyday for the previous nine months, suggesting at length to the sensitive that the end of the world was nigh and that no thinking person was able with credulity much to deny the endís apparent certainty, one can readily understand the sentiment of the mother, if not her action, in desiring death for herself and her young charge, lest they both would together have to confront the prospect of the world to come from this Hitlerian-Japanese morass slowly encircling their lives from afar, yet stuck close enough in their midst to be daily appreciated as reality, her own country being drawn deeper and deeper into the depths of the death throes instilled by a military state for the sake of expediency to defeat the military states, the totalitarian-feudalistic regimes, abroad the world slowly enslaving their conquered.

The piece does not inform, perhaps out of a sense of decorum to the times and not wishing to spawn others to the same end, whether perhaps the husband and father was at war or had already been killed in the battle.

Regardless, much was the sacrifice being made, much the more was yet to come, and for all, whether directly engaged in the fight or not, of this brave war generation.

"Adroit Man" assesses the Presidentís tough message to Congress of the previous day and the even tougher talk at his press conference on the morning of this date. And it was a tough talk, especially in light of its coming just two months before the mid-term congressional elections. The President was talking tough to farmers and their allies, talking tough to the wealthy industrialists and their allies, talking of substantially increased taxes, talking of across-the-board wage limitations and thus talking tough to labor and its alliesóeach a group on which the very politicians to whom he appealed for patriotic support depended for votes come November. And, to top it, he wanted it all accomplished not by December 1 but by October 1, in advance of the election.

Even as the popular third term President, now rounding out his tenth year in the White House, was he expecting too much, far too much from mere mortal politicians?

We shall see.

A quote from recent Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Lt.-Commander John D. Bulkeley, PT Boat commander, indicates his thought that the captains of these boats were the finest of fighting men, the finest he had seen.

The country as a whole would, in effect, honor these young PT Boat skippers as a group by electing one of their number to the presidency in 1960.

John J. McCloy, in another clipped quote, tells of the importance of air power to victory in the war. "There They Go" echoes the sentiment from Maj.-General Carl Spaatz, recently appointed commander of the U.S. Air Forces in Europe, in his case speaking specifically of the Flying Fortress pilots.

The country as a whole would, in effect, honor these young airmen as a group by electing one of their number to the presidency in 1988.

Dorothy Thompson writes of a lack of direction and cause in the country, one not articulated sufficiently to provide the young fighting man a basis for future vision. She quotes a letter from a young soldier in the Army writing her of this vast indifference, indicating that the soldierís will to fight was based solely on the notion of survival, not on any common, sustaining vision of democracy in action or, as in the last war of his fathers, the common goal, at least as he perceived it, to make it "the war to end all wars".

His letter is practically timeless in time of war. Indeed, it could have been written by any young person coming of age fit for service in the military in the latter half of the 1960ís and early 1970ís. Such letters often were.

And yet, in that latter time, just as with the young soldier in 1942, we were faced with the unerring certainty that our fathers had gone to war in 1942 with a smile on their faces, a sense of common purpose and normative conduct by which to govern their aspirations dutifully and firmly set in their minds to victory. It was, we were informed, because they were a stronger, less coddled generation than ourselves. They were governed decisively by a firm commander-in-chief who guided them purposefully to victory, not appeasers and coddlers as were we.

But reading that letter of the soldier of 1942 carefully, the editorial columnís negative response to Ms. Thompsonís call for vision notwithstanding, that the fight for the age-old common causes of home and country and family was quite enough to sustain the effort, one inexorably has to come to the conclusion that it is war itself which is the enemy of mankind, and no matter how strong the leadership, no matter how strong the purpose, no matter how evil the enemy, that it is war itself which will always pose the dual existential questions to the young soldier and the would-be young soldier: What the hell are we fighting for? What the hell are we doing over there?

It would take going over there, watching oneís fellows who had trained in arms in safer territory blown to bits, to provide the final will to fight.

Ms. Thompson had, just in June, indicated in a column that what was needed was focus of the democracies on the totalitarian nature of the enemy, that the war was one against Nazism and Fascism as a philosophy, and that therefore it was necessary to distinguish adequately for the country the ramifications to its subjects of such regimes when compared to citizens governed democratically by representative government sensitive to the common weal.

We disagree with "Word-Warrior", that Ms. Thompson was out to lunch on this topic, that all that was needed was the will to fight against the horde for protection of country, home and family. For with the war still three thousand miles away from each coast, there was plentiful reason to doubt that premise even now. Nine months had gone by since Pearl Harbor, and the war was still at least three thousand miles distant. Was it not still "over there" in terms of threat to country, home and family? Was it not sufficient to provide the machines and tools of war, with all of industry and labor now fully engaged on war-footing, all new cars off the lots, no rubber, rationed gas, little to do but work in war industry, with all of the daily routine of society cast on war-footing, with most ordinary needs, soon to include even meat, subject to allotment by ration cards? Was the sacrifice of men and their lives, the lives of family breadwinners, truly necessary for that war "over there" to be won?

Well, it was won, and with great hardship and sacrifice and huge numbers of lost Americans, fully a quarter million lives in the ensuing three years from this early war period for America of September, 1942, more than any other war in which America has ever engaged, indeed more than all of the soldiers killed in all previous wars involving America--yet still, even so, paling in numbers beside the millions of losses suffered collectively by the other Allies, especially China and Russia, and by the Axis nations who started the thing.

The enemy, the evil, on last analysis, is always war itself and the tendency in man to want to resolve differences deemed unresolvable otherwise through rational discussion and diplomacy and mutual compromise of the demands of each side, by hurling at one another rocks and sticks and brickbats, until someone finally is killed, who then must be avenged, according to the ancient law of men.

Yet here she stood, baffled and confused, glowering sullenly into the shining face of the other woman's glorious success--and she saw it, she knew it, she felt its outrage, but she had no word to voice her sense of an intolerable wrong. All she knew was that she had been stiffened and thickened by the same years that had given the other woman added grace and suppleness, that her skin had been dried and sallowed by the same lights and weathers that had added lustre to the radiant beauty of the other, and that even now her spirit was soured by her knowledge of ruin and defeat while in the other woman there coursed for ever an exquisite music of power and control, of health and joy.

Yes, she saw it plainly enough. The comparison was cruelly and terribly true, past the last atom of hope and disbelief. And as she stood there before her mistress with the weary distemper in her eyes, enforcing by a stern compulsion the qualities of obedience and respect into her voice, she saw, too, that the other woman read the secret of her envy and frustration, and that she pitied her because of it. And for this Nora's soul was filled with hatred, because pity seemed to her the final and intolerable indignity.

In fact, although the kind and jolly look on Mrs. Jack's lovely face had not changed a bit since she had greeted the maid, her eye had observed instantly all the signs of the unwholesome fury that was raging in the woman, and with a strong emotion of pity, wonder, and regret she was thinking:

"She's been at it again! This is the third time in a week that she's been drinking. I wonder what it is--I wonder what it is that happens to that kind of person."

****

Is the news, then, like America? No, it's not--and Fox, unlike the rest of you, mad masters, turns the pages knowing it is just the news and not America that he reads there in his Times.

The news is not America, nor is America the news--the news is in America. It is a kind of light at morning, and at evening, and at midnight in America. It is a kind of growth and record and excrescence of our life. It is not good enough--it does not tell our story--yet it is the news!

Fox reads (proud nose sharp-sniffing with a scornful relish):

An unidentified man fell or jumped yesterday at noon from the twelfth story of the Admiral Francis Drake Hotel, corner of Hay and Apple Streets, in Brooklyn. The man, who was about thirty-five years old, registered at the hotel about a week ago, according to the police, as C. Green. Police are of the opinion that this was an assumed name. Pending identification, the body is being held at the King's County Morgue.

This, then, is news. Is it also the whole story, Admiral Drake? No! Yet we do not supply the whole story--we who have known all the lights and weathers of America--as Fox supplies it now:

Well, then, it's news, and it happened in your own hotel, brave Admiral Drake. It didn't happen in the Penn-Pitt at Pittsburgh, nor the Phil-Penn at Philadelphia, nor the York-Albany at Albany, nor the Hudson-Troy at Troy, nor the Libya-Ritz at Libya Hill, nor the Clay-Calhoun at Columbia, nor the Richmond-Lee at Richmond, nor the George Washington at Easton, Pennsylvania, Canton, Ohio, Terre Haute, Indiana, Danville, Virginia, Houston, Texas, and ninety-seven other places; nor at the Abraham Lincoln at Springfield, Massachusetts, Hartford, Connecticut, Wilmington, Delaware, Cairo, Illinois, Kansas City, Missouri, Los Angeles, California, and one hundred and thirty-six other towns; nor at the Andrew Jackson, the Roosevelt (Theodore or Franklin--take your choice), the Jefferson Davis, the Daniel Webster, the Stonewall Jackson, the U.S. Grant, the Commodore Vanderbilt, the Waldorf-Astor, the Adams House, the Parker House, the Palmer House, the Taft, the McKinley, the Emerson (Waldo or Bromo), the Harding, the Coolidge, the Hoover, the Albert G. Fall, the Harry Daugherty, the Rockefeller, the Harriman, the Carnegie or the Frick, the Christopher Columbus or the Leif Ericsson, the Ponce-de-Leon or the Magellan, in the remaining eight hundred and forty-three cities of America--but at the Francis Drake, brave Admiral--your own hotel--so, of course, you'll want to know what happened.

"An unidentified man"--well, then, this man was an American. "About thirty-five years old" with "an assumed name"--well, then, call him C. Green as he called himself ironically in the hotel register. C. Green, the unidentified American, "fell or jumped," then, "yesterday at noon...in Brooklyn"--worth nine lines of print in to-day's Times--one of seven thousand who died yesterday upon this continent--one of three hundred and fifty who died yesterday in this very city (see dense, close columns of obituaries, page 15: begin with "Aaronson", so through the alphabet to "Zorn"). C. Green came here "a week ago"----

And came from where? From the deep South, or the Mississippi Valley, or the Middle West? From Minneapolis, Bridgeport, Boston, or a little town in Old Catawba? From Scranton, Toledo, St. Louis, or the desert whiteness of Los Angeles? From the pine barrens of the Atlantic coastal plain, or from the Pacific shore?

And so--was what, brave Admiral Drake? Had seen, felt, heard, smelled, tasted--what?

Had known--what? Had known all our brutal violence of weather: the burned swelter of July across the nation, the smell of the slow, rank river, the mud, the bottom lands, the weed growth, and the hot, coarse, humid fragrance of the corn. The kind that says: "Jesus, but it's hot!"--pulls off his coat, and mops his face, and goes in shirt-sleeves in St. Louis, goes to August's for a Swiss on rye with mustard, and a mug of beer. The kind that says: "Damn! It's hot!" in South Carolina, slouches in shirt-sleeves and straw hat down South Main Street, drops into Evans Drug Store for a dope, says to the soda jerker: "Is it hot enough fer you to-day, Jim?" The kind that reads in the paper of the heat, the deaths, and the prostration, reads it with a certain satisfaction, hangs on grimly day by day and loses sleep at night, can't sleep for heat, is tired in the morning, says: "Jesus! It can't last for ever!" as heat lengthens into August, and the nation gasps for breath, and the green that was young in May now mottles, fades and bleaches, withers, goes heat-brown. Will boast of coolness in the mountains, Admiral Drake. "Always cool at night! May get a little warm around the middle of the day, but you'll sleep with blankets every night."

Then summer fades and passes, and October comes. Will smell smoke then, and feel an unsuspected sharpness, a thrill of nervous, swift elation, a sense of sadness and departure. C. Green doesn't know the reason, Admiral Drake, but lights slant and shorten in the afternoon, there is a misty pollen of old gold in light at noon, a murky redness in the lights of dusk, a frosty stillness, and the barking of the dogs; the maples flame upon the hills, the gums are burning, bronze the oak leaves and, the aspens yellow; then come the rains, the sodden dead-brown of the fallen leaves, the smoke-stark branches--and November comes.

Waiting for winter in the little towns, and winter comes. It is really the same in big towns and the cities, too, with the bleak enclosure of the winter multiplied. In the commerce of the day, engaged and furious, then darkness, and the bleak monotony of "Where shall we go? What shall we do?" The winter grips us, closes round each house--the stark, harsh light encysts us--and C. Green walks the streets. Sometimes hard lights burn on him, Admiral Drake, bleak faces stream beneath the lights, amusement signs are winking. On Broadway, the constant blaze of sterile lights; in little towns, no less, the clustered raisins of hard light on Main Street. On Broadway, swarming millions up to midnight; in little towns, hard lights and frozen silence--no one, nothing, after ten o'clock. But in the hearts of C. Greens everywhere, bleak boredom, undefined despair, and "Christ! Where shall I go now? When will winter end?"

So longs for spring, and wishes it were Saturday, brave Admiral Drake.

Saturday night arrives with the thing that we are waiting for. Oh, it will come to-night; the thing that we have been expecting all our lives will come to-night, on Saturday! 'On Saturday night across America we are waiting for it, and ninety million Greens go moth-wise to the lights to find it. Surely it will come to-night! So Green goes out to find it, and he finds--hard lights again, saloons along Third Avenue, or the Greek's place in a little town--and then hard whisky, gin, and drunkenness, and brawls and fights and vomit.

Sunday morning, aching head. Sunday afternoon, and in the cities the chop-suey signs wink on and flash their sterile promises of unborn joy.

Sunday night, and the hard stars, and the bleak enclosures of our wintry weather--the buildings of old rusty brick, in cold enclosed, the fronts of old stark brown, the unpainted houses, the deserted factories, wharves, piers, warehouses, and office buildings, the tormented shabbiness of Sixth Avenues; and in the smaller towns, bleak Main Streets, desolate with shabby store fronts and be-raisined clusters of lamp standards, and in the residential streets of wooden houses (dark by ten o'clock), the moaning of stark branches, the stiff lights, limb-bepatterned, shaking at street corners. The light shines there with wintry bleakness on the clapboard front and porch of a shabby house where the policeman lives--blank and desolate upon the stuffy, boxlike little parlour where the policeman's daughter amorously receives--and almost--not quite--gives. Hot, fevered, fearful, and insatiate, it is all too close to the cold street light--too creaking, panting, flimsy-close to others in the flimsy house--too close to the policeman's solid and slow-creaking tread--yet somehow valiant, somehow strong, somehow triumphant over the stale varnish of the little parlour, the nearness of the street, the light, the creaking boughs, and papa's tread--somehow triumphant with hot panting, with rose lips and tender tongue, white underleg and tight-locked thighs--by these intimacies of fear and fragrant hot desire will beat the ashen monotone of time and even the bleak and grey duration of the winter out.

Does this surprise you, Admiral Drake?

"But Christ!"--Green leaves the house, his life is bitter with desire, the stiff light creaks. "When will it end?" thinks Green. "When will spring come?"

It comes at last unhoped for, after hoping, comes when least expected, and when given up. In March there is a day that's almost spring, and C. Green, strong with will to have it so, says: "Well, it's here"--and it is gone like smoke. You can't look spring too closely in the eye in March. Raw days return, and blown light, and gusty moanings of the wind. Then April comes, and small, soaking rain. The air is wet and raw and chilled, but with a smell of spring now, a smell of earth, of grass exploding in small patches, here and there a blade, a bud, a leaf. And spring comes, marvellous, for a day or two--"It's here!" Green thinks. "It's here at last!"--and he is wrong again. It goes, chill days and greyness and small, soaking rains return. Green loses hope. "There is no spring!" he says. "You never get spring any more; you jump from winter into summer--we'll have summer now and the hot weather before you know it."

Then spring comes--explodes out of the earth in a green radiance--comes up overnight! It's April twenty-eighth--the tree there in the city backyard is smoke-yellow, feathered with the striplings of young leaf! It's April twenty-ninth--the leaf, the yellow, and the smoke have thickened overnight. April thirtieth--you can watch it grow and thicken with your eye! Then May the first--the tree's in leaf now, almost full and dense, young, feather-fresh! The whole spring has exploded from the earth!

All's explosive with us really, Admiral Drake--spring, the brutal summer, frost, October, February in Dakota with fifty-one below, spring floods, two hundred drowning along Ohio bottoms, in Missouri, in New England, all through Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Tennessee. Spring shot at us overnight, and everything with us is vast, explosive, floodlike. A few hundred dead in floods, a hundred in a wave of heat, twelve thousand in a year by murder, thirty thousand with the motor-car--it all means nothing here. Floods like this would drown out France; death like this would plunge England in black mourning; but in America a few thousand C. Greens more or less, drowned, murdered, killed by motor-cars, or dead by jumping out of windows on their heads--well, it just means nothing to us--the next flood, or next week's crop of death and killings, wash it out. We do things on a large scale, Admiral Drake.

The tar-smell in the streets now, children shouting, and the smell of earth; the sky shell-blue and faultless, a sapphire sparkle everywhere; and in the air the brave stick-candy whippings of a flag. C. Green thinks of the baseball games, the raw-hide arm of Lefty Grove, the resilient crack of ashwood on the horsehide ball, the waiting pockets of the well-oiled mitts, the warm smell of the bleachers, the shouted gibes of shirt-sleeved men, the sprawl and monotone of inning after inning. (Baseball's a dull game, really; that's the reason that it is so good. We do not love the game so much as we love the sprawl and drowse and shirt-sleeved apathy of it.) On Saturday afternoon, C. Green goes out to the ball park and sits there in the crowd, awaiting the sudden sharpness and the yell of crisis. Then the game ends and the crowd flows out across the green turf of the playing-field. Sunday, Green spends the day out in the country in his flivver, with a girl.

Then summer comes again, heat-blazing summer, humid, murked with mist, sky-glazed with brutal weariness--and C. Green mops his face and sweats and says: "Jesus! Will it never end?"

This, then, is C. Green "thirty-five years old"--"unidentified"--and an American. In what way an American? In what way different from the men you knew, old Drake?

When the ships bore home again and Cape St. Vincent blazed in Spaniard's eye--or when old Drake was returning with his men, beating coastwise from strange seas abreast, past the Scilly Isles towards the slant of evening fields, chalk cliffs, the harbour's arms, the town's sweet cluster and the spire--where was Green?

When, in red-oak thickets at the break of day, coon-skinned, the huntsmen of the wilderness lay for bear, heard arrows rattling in the laurel leaves, the bullets' whining plunk, and waited with cocked musket by the tree--where was Green?

Or when, with strong faces turning towards the setting sun, hawk-eyed and Indian-visaged men bore gun-stocks on the western trails and sternly heard the fierce war-whoops around the Painted Buttes--where, then, was Green?

Was never there with Drake's men in the evening when the sails stood in from the Americas! Was never there beneath the Spaniard's swarthy eye at Vincent's Cape! Was never there in the red-oak thicket in the morning! Was never there to hear the war-cries round the Painted Buttes!

No, no. He was no voyager of unknown seas, no pioneer of western trails. He was life's little man, life's nameless cypher, life's man-swarm atom, life's American--and now he lies disjected and exploded on a street in Brooklyn!

He was a dweller in mean streets, was Green, a man-mote in the jungle of the city, a resident of grimy steel and stone, a mole who burrowed in rusty brick, a stunned spectator of enormous salmon-coloured towers, hued palely with the morning. He was a renter of shabby wooden houses in a little town, an owner of a raw new bungalow on the outskirts of the town. He was a waker in bleak streets at morning, an alarm-clock watcher, saying: "Jesus, I'll be late."--a fellow who took short cuts through the corner lot, behind the advertising signs; a fellow used to concrete horrors of hot day and blazing noon; a man accustomed to the tormented hodge-podge of our architectures, used to broken pavements, ash-cans, shabby store fronts, dull green paint, the elevated structure, grinding traffic, noise, and streets be-tortured with a thousand bleak and dismal signs. He was accustomed to the gas tanks going out of town, he was an atom of machinery in an endless flow, going, stopping, going to the winking of the lights; he tore down concrete roads on Sundays, past the hot-dog stands and filling-stations; he would return at darkness; hunger lured him to the winking splendour of chop-suey signs; and midnight found him in The Coffee Pot, to prowl above a mug of coffee, tear a coffee-cake in fragments, and wear away the slow grey ash of time and boredom with other men in grey hats and with skins of tallow-grey, at Joe the Greek's.

C. Green could read (which Drake could not), but not too accurately; could write, too (which the Spaniard couldn't), but not too well. C. Green had trouble over certain words, spelled them out above the coffee mug at midnight, with a furrowed brow, slow-shaping lips, and "Jesus!" when news stunned him--for he read the news. Preferred the news with pictures, too, girls with voluptuous legs crossed sensually, dresses above the knees, and plump dolls' faces full of vacant lechery. Green liked news "hot"--not as Fox knows it, not subtly sniffing with strange-scornful nostrils for the news behind the news--but straight from the shoulder--socko!--biff!--straight off the griddle, with lots of mustard, shapely legs, roadside wrecks and mutilated bodies, gangsters' molls and gunmen's hideouts, tallow faces of the night that bluntly stare at flashlight lenses--this and talk of "heart-balm", "love-thief", "sex-hijacker"--all of this liked Green.

Yes, Green liked the news--and now, a bit of news himself (nine lines of print in Times), has been disjected and exploded on a Brooklyn pavement!

Well, such was our friend, C. Green, who read, but not too well; and wrote, but not too easily; who smelled, but not too strongly; felt, but not too deeply; saw, but not too clearly--yet had smelled the tar in May, smelled the slow, rank yellow of the rivers, and the clean, coarse corn; had seen the slants of evening on the hill-flanks in the Smokies, and the bronze swell of the earth, the broad, deep red of Pennsylvania barns, proud-proportioned and as dominant across the fields as bulls; had felt the frost and silence in October; had heard the whistles of the train wail back in darkness, and the horns of New Year's Eve, and--"Jesus! There's another year gone by! What now?"

No Drake was he, no Spaniard, no coon-skin cap, no strong face burning west. Yet, in some remote and protoplasmic portion, he was a little of each of these. A little Scotch, perhaps, was Green, a little Irish, English, Spanish even, and some German--a little of each part, all compacted and exploded into nameless atom of America!

No. Green--poor little Green--was not a man like Drake. He was just a cinder out of life--for the most part, a thinker of base thoughts, a creature of unsharpened, coarse perceptions. He was meagre in the hips, he did not have much juice or salt in him. Drake gnawed the beef from juicy bones in taverns, drank tankards of brown ale, swore salty curses through his whiskers, wiped his mouth with the back of his hard hand, threw the beef bone to his dog, and pounded with his tankard for more ale. Green ate in cafeterias, prowled at midnight over coffee and a doughnut or a sugar-coated bun, went to the chop-suey joint on Saturday nights and swallowed chow mein, noodle soup, and rice. Green's mouth was mean and thin and common, it ran to looseness and a snarl; his skin was grey and harsh and dry; his eyes were dull and full of fear. Drake was self-contained: the world his oyster, seas his pastures, mighty distances his wings. His eyes were sea-pale (like the eyes of Fox); his ship was England. Green had no ship, he had a motor-car, and tore down concrete roads on Sunday, and halted with the lights against him with the million other cinders hurtling through hot space. Green walked on level concrete sidewalks and on pavements grey, through hot and grimy streets past rusty tenements. Drake set his sails against the west, he strode the buoyant, sea-washed decks, he took the Spaniard and his gold, and at the end he stood in to the sweet enfoldments of the spire, the clustered town, the emerald fields that slope to Plymouth harbour--then Green came!

We who never saw brave Drake can have no difficulty conjuring up an image of the kind of man he was. With equal ease we can imagine the bearded Spaniard, and almost hear his swarthy oaths. But neither Drake nor Spaniard could ever have imagined Green. Who could have foreseen him, this cypher of America, exploded now upon a street in Brooklyn?

Behold him, Admiral Drake! Observe the scene now! Listen to the people! Here is something strange as the Armadas, the gold-laden cargoes of the bearded Spaniards, the vision of unfound Americas!

What do you see here, Admiral Drake?

****

To live alone as George was living, a man should have the confidence of God, the tranquil faith of a monastic saint, the stern impregnability of Gibraltar. Lacking these, he finds that there are times when anything, everything, all and nothing, the most trivial incidents, the most casual words, can in an instant strip him of his armour, palsy his hand, constrict his heart with frozen horror, and fill his bowels with the grey substance of shuddering impotence and desolation. Sometimes it would be a sly remark dropped by some all-knowing literary soothsayer in the columns of one of the more leftish reviews, such as:

"Whatever has become of our autobiographical and volcanic friend, George Webber? Remember him? Remember the splash he made with that so-called 'novel' of his a few years back? Some of our esteemed colleagues thought they detected signs of promise there. We ourselves should have welcomed another book from him, just to prove that the first was not an accident. But tempus fugit, and where is Webber? Calling Mr. Webber! No answer? Well, a pity, perhaps; but then, who can count the number of one-book authors? They shoot their bolt, and after that they go into the silence and no more is heard from them. Some of us who were more than a little doubtful about that book of Webber's, but whose voices were drowned out by the Oh's and Ah's of those who rushed headlong to proclaim a new star rising in the literary firmament, could now come forward, if we weren't too kindly disposed towards our more emotional brethren of the critical fraternity, and modestly say: 'We told you so!'"

Sometimes it would be nothing but a shadow passing on the sun, sometimes nothing but the gelid light of March falling on the limitless, naked, sprawling ugliness and squalid decencies of Brooklyn streets. Whatever it was, at such a time all joy and singing would go instantly out of day, Webber's heart would drop out of him like a leaden plummet, hope, confidence, and conviction would seem lost for ever to him, and all the high and shining truth that he had ever found and lived and known would now turn false to mock him. Then he would feel like one who walked among the dead, and it would be as if the only things that were not false on earth were the creatures of the death-in-life who moved for ever in the changeless lights and weathers of red, waning, weary March and Sunday afternoon.

These hideous doubts, despairs, and dark confusions of the soul would come and go, and George knew them as every lonely man must know them. For he was united to no image save that image which he himself created. He was bolstered by no knowledge save that which he gathered for himself out of his own life. He saw life with no other vision save the vision of his own eyes and brain and senses. He was sustained and cheered and aided by no party, was given comfort by no creed, and had no faith in him except his own.

****

Is this abridgement and this definition just, dear Fox? Yes, for I have seen every syllable of it in you a thousand times. I have learned every accent of it from yourself. You said one time, when I had spoken of you in the dedication of a book, that what I had written would be your epitaph. You were mistaken. Your epitaph was written many centuries ago: Ecclesiastes is your epitaph. Your portrait had been drawn already in the portrait the great Preacher had given of himself. You are he, his words are yours so perfectly that if he had never lived or uttered them, all of him, all of his great and noble Sermon, could have been derived afresh from you.

If I could, therefore, define your own philosophy--and his--I think I should define it as the philosophy of a hopeful fatalism. Both of you are in the essence pessimists, but both of you are also pessimists with hope. From both of you I learned much, many true and hopeful things. I learned, first of all, that one must work, that one must do what work he can, as well and ably as he can, and that it is only the fool who repines and longs for what is vanished, for what might have been but is not. I learned from both of you the stern lesson of acceptance: to acknowledge the tragic underweft of life into which man is born, through which he must live, out of which he must die. I learned from both of you to accept that essential fact without complaint, but, having accepted it, to try to do what was before me, what I could do, with all my might.

And, curiously--for here comes in the strange, hard paradox of our twin polarity--it was just here, I think, where I was so much and so essentially in confirmation with you, that I began to disagree. I think almost that I could say to you: "I believe in everything you say, but I do not agree with you"--and so state the root of our whole trouble, the mystery of our eventual cleavage and our final severance. The little tongues will wag--have wagged, I understand, already--will propose a thousand quick and ready explanations (as they have)--but really, Fox, the root of the whole thing is here.

In one of the few letters that you ever wrote to me--a wonderful and moving one just recently--you said:

"I know that you are going now. I always knew that it would happen. I will not try to stop you, for it had to be. And yet, the strange thing is, the hard thing is, I have never known another man with whom I was so profoundly in agreement on all essential things."

And that is the strange, hard thing, and wonderful and mysterious; for, in a way the little clacking tongues can never know about, it is completely true. Still, there is our strange paradox: it seems to me that in the orbit of our world you are the North Pole, I the South--so much in balance, in agreement--and yet, dear Fox, the whole world lies between.

'Tis true, our view of life was very much the same. When we looked out together, we saw man burned with the same sun, frozen by the same cold, beat upon by the hardships of the same impervious weathers, duped by the same gullibility, self-betrayed by the same folly, misled and baffled by the same stupidity. Each on the opposing hemisphere of his own pole looked out across the spinning orbit of this vexed, tormented world, and at the other, and what each saw, the picture that each got, was very much the same. We not only saw the stupidity and the folly and the gullibility and the self-deception of man, but we saw his nobility, courage, and aspiration, too. We saw the wolves that preyed upon him and laid him waste--the wild scavangers of greed, of fear, of privilege, of power, of tyranny, of oppression, of poverty and disease, of injustice, cruelty, and wrong--and in what we saw of this as well, dear Fox, we were agreed.

Why, then, the disagreement? Why, then, the struggle that ensued, the severance that has now occurred? We saw the same things, and we called them by the same names. We abhorred them with the same indignation and disgust--and yet, we disagreed, and I am making my farewell to you. Dear friend, the parent and the guardian of my spirit in its youth, the thing has happened and we know it. Why?

I know the answer, and the thing I have to tell you now is this: Beyond the limits of my own mortality, the stern acknowledgment that man was born to live, to suffer, and to die--your own and the great Preacher's creed--I am not, cannot be, confirmed to more fatality. Briefly, you thought the ills which so beset mankind were irremediable: that just as man was born to live, to suffer, and to die, so was he born to be eternally beset and preyed upon by all the monsters of his own creation--by fear and cruelty, by tyranny and power, by poverty and wealth. You felt, with the stern fatality of resignation which is the granite essence of your nature, that these things were doomed to be, and be for ever, because they had always been, and were inherent in the tainted and tormented soul of man.

Dear Fox, dear friend, I heard you and I understood you--but could not agree. You felt--I heard you and I understood--that if old monsters were destroyed, new ones would be created in their place. You felt that if old tyrannies were overthrown, new ones, as sinister and evil, would reign after them. You felt that all the glaring evils in the world around us--the monstrous and perverse unbalance between power and servitude, between want and plenty, between privilege and burdensome discrimination--were inevitable because they had always been the curse of man and were the prime conditions of his being. The gap between us widened. You stated and affirmed--I heard you, but could not agree.

To state your rule and conduct plainly, I think I never knew a kinder or a gentler man, but I also never knew a man more fatally resigned. In practice--in life and conduct--I have seen the Sermon of the Preacher work out in you like a miracle. I have seen you grow haggard and grey because you saw a talent wasted, a life misused, work undone that should be done. I have seen you move mountains to save something which, you felt, was worth the effort and could be saved. I have seen you perform prodigies of labour and patience to pull a drowning man of talent out of the swamp of failure into which his life was sinking; and at each successive slipping back, so far from acknowledging defeat with resignation and regret, you made your eyes flash fire and you will toughen to the hardness of forged steel as I saw you strike your hand upon the table and heard you whisper, with an almost savage intensity of passion: "He must not go. He is not lost. I will not, and he must not, let it happen!"

To give this noble virtue of your life the etching of magnificence it deserves, it is your due to have it stated here. For, without it, there can be no proper understanding of your worth, your true dimension. To describe the acquiescence of your stern fatality without first describing the inspired tenacity of your effort would be to give a false and insufficient picture of the strangest and the most familiar, the most devious and the most direct, the simplest and the most complex figure that this nation and this generation have produced.

To say that you looked on at all the suffering and injustice of this vexed, tormented world with the toleration of resigned fatality without telling also of your own devoted and miraculous effort to save what could be saved, would not do justice to you. No man ever better fulfilled the injunction of the Preacher to lay about him and to do the work at hand with all his might. No man ever gave himself more wholly, not only to the fulfilment of that injunction for himself, but to the task of saving others who had failed to do it, and who might be saved. But no man ever accepted the irremediable with more quiet unconcern. I think you would risk your life to save that of a friend who put himself uselessly and wantonly in peril, but I know, too, that you would accept the fact of unavoidable death without regret. I have seen you grow grey-faced and hollow-eyed with worry over the condition of a beloved child who was suffering from a nervous shock or ailment that the doctors could not diagnose. You found the cause eventually and checked it; but I know that if the cause had been fatal and incurable, you would have accepted that fact with a resignation as composed as your own effort was inspired.

All of this makes the paradox of our great difference as bard and strange as the paradox of our polarity. And in this lies the root of trouble and the seed of severance. Your own philosophy has led you to accept the order of things as they are because you have no hope of changing them; and if you could change them, you feel that any other order would be just as bad. In everlasting terms--those of eternity--you and the Preacher may be right: for there is no greater wisdom than the wisdom of Ecclesiastes, no acceptance finally so true as the stern fatalism of the rock. Man was born to live, to suffer, and to die, and what befalls him is a tragic lot. There is no denying this in the final end. But we must, dear Fox, deny it all along the way.

Mankind was fashioned for eternity, but Man-Alive was fashioned for a day. New evils will come after him, but it is with the present evils that he is now concerned. And the essence of all faith, it seems to me, for such a man as I, the essence of religion for people of my belief, is that man's life can be, and will be, better; that man's greatest enemies, in the forms in which they now exist--the forms we see on every hand of fear, hatred, slavery, cruelty, poverty, and need--can be conquered and destroyed. But to conquer and destroy them will mean nothing less than the complete revision of the structure of society as we know it. They cannot be conquered by the sorrowful acquiescence of resigned fatality. They cannot be destroyed by the philosophy of acceptance--by the tragic hypothesis that things as they are, evil as they are, are as good and as bad as, under any form--they will ever be. The evils that we hate, you no less than I, cannot be overthrown with shrugs and sighs and shakings of the head, however wise. It seems to me that they but mock at us and only become more bold when we retreat before them and take refuge in the affirmation of man's tragic average. To believe that new monsters will arise as vicious as the old, to believe that the great Pandora's box of human frailty, once opened, will never show a diminution of its ugly swarm, is to help, by just that much, to make it so for ever.

You and the Preacher may be right for all eternity, but we Men-Alive, dear Fox, are right for Now. And it is for Now, and for us the living, that we must speak, and speak the truth, as much of it as we can see and know. With the courage of the truth within us, we shall meet the enemy as they come to us, and they shall be ours. And if, once having conquered them, new enemies approach, we shall meet them from that point, from there proceed. In the affirmation of that fact, the continuance of that unceasing war, is man's religion and his living faith.

--from You Canít Go Home Again, Chaps. 11, 28, 31, and 47,

by Thomas Wolfe, post., 1940

Then the old slumbering Southern train went again north out of the Egyptian station, there in the lonely stretch of desolate Charlotte--but it would be back again.

We urge the Congress not to compromise on the health of the nation. Pass the Presidentís plan with the public option. Try it if you dare to do anything other than the bidding of the pocketbooks who keep you in Congress to do nothing but the bidding of the pocketbooks. Do something constructive for a Change. Put the people ahead of your healthy-wealthy contributorsí pocketbooks.

For freedom of speech, of religion, from fear, and from want begin and end with freedom of health. And without freedom of health, no nation may long endure or enjoy wealth, as it comes otherwise slowly to live in want and fear, chilled thus in religion, chilled thus in speech, chilled thus in division, as it comes then to live in war.

Or, once again, will it be a trillion in tribute for corporate welfare, and only an ounce of prevention, a penny, for the citizens' health care?

What do you think, Fox?

![]()

![]()