![]()

The Charlotte News

Wednesday, May 6, 1942

FOUR EDITORIALS

![]()

![]()

Site Ed. Note: The major news on the front page was the fall of Corregidor’s 10,000 stalwart defenders under the command of General Jonathan Wainwright. "The Rock" of Manila Bay and thus the approaches to the Harbor were now completely in Japanese hands. The fortress maintained by the "grim , gaunt, and ghostly", as General MacArthur, from his recently established headquarters in Melbourne, termed the contingent who had withstood the unrelenting Japanese assault for a grueling four weeks with little food and ammunition, cut off from the world after Bataan had fallen April 9, was now gone. And with it, the last Allied foothold in the Philippines. It would be so until February, 1945.

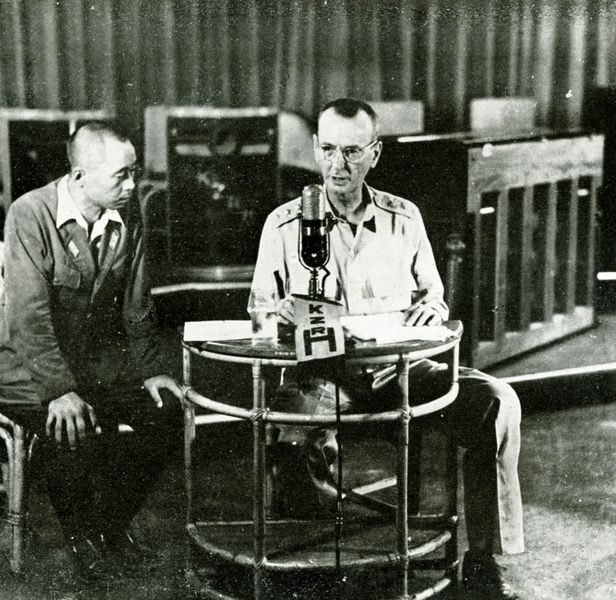

General Wainwright himself, as depicted below while scrutinized by his Japanese captor, would announce to the Philippines its final surrender. General Wainwright and his men would now join the humiliation, death, and starvation accompanying the 70,000 American and Filipino prisoners on their march north following the surrender of Bataan. General Wainwright would survive the war in a concentration camp, to be freed in August, 1945.

The editorial page, too, notes the event, indicating its strategic significance in bogging down for five months hundreds of thousands of Japanese troops so that they were not available in China, the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, or Burma, enabling the Allies to build defensive positions and counter-strike capability in Australia. The same story was true, of course, in Burma for the British and the Chinese contingents holding for as long as possible their defensive positions against the Japanese onslaught, maintaining now the last of the approaches to the vital Chinese supply route along the Burma Road in the north, in and around Mandalay.

"No Easy Way" waxes profoundly prophetic in its caution against any fanciful optimism to be garnered from the British occupation of Madagascar, a peripheral island without significant resources, which, while significant to the Japanese in the fight for the Middle East and India and so important as a defensive bulwark, still was no more than that.

The piece accurately forecasts that so, too, would come to be characterized the presently recurrent RAF raids on Germany and occupied France, that these daring missions, while necessary preludes, could not supplant the sine qua non for re-acquisiton of the territory which the Nazi had taken—the bloody ground fighting to come. The same, the editorial again accurately presages, would be true in the Pacific.

It would be so, and for three more bloody years, each day’s front page providing the stark testimony to lend credence to the prediction, each column of print full of more bloody news, full of more cold remembrance of the dead to come.

"Hail Enemies" speaks of the toast of Laval to Japanese diplomats at Vichy, the cream of the jest being that it occurred as Madagascar--the plum in the Indian Ocean which could have provided the essential stepping stone for the Japanese to capture India, open a back door into the Suez, trap the British in Egypt and Syria between the guns of the Japanese and those of the Nazi, and join their Wolfish comrades of the Black Forest in hellish consanguinity for the conquest of the world--, had fallen quickly, though with reported heavy casualties, to the British.

The piece further speaks of the way in which Japanese-Vichy diplomacy had transpired thus far in the war, case in point being the previous summer’s transfer of Indochina into Japanese hands: the seeking of small concessions by the Japanese and then, once the foot was in the door, slamming wide its sweep into the face of their too gracious host. Such tactics had enabled the full occupation of Indochina and the consequent establishment of the entrepôt from which distribution of troops and supplies were accomplished to the Philippines, Singapore and the Malay Peninsula, Hong Kong, Burma, and the Dutch East Indies--the origins of the "domino theory" which led to full-scale American commitment to the Vietnam War in 1964, to thwart the perceived potential for the Chinese Communists to occupy all of Vietnam, to the same end of ocupying all of the strategic points in the southwest Pacific, with the threat of nuclear conflict then hanging in the balance.

Paul Mallon speaks of the possibility of a military coup in Germany, with the insurgents then seeking an armistice reminiscent of 1918. He cautions against it, should it be in the offing at some point down the road, that such expedience would only lead, in another twenty years, to yet another confrontation on the world stage.

While it did not happen that way, and while Germany this time, instead of being left again on its own to resurrect itself as the Phoenix in the New Sun, was divided between the Soviets and the other Allies and provided, on the Western side at least, protectorate status, there nevertheless, twenty years later, would come, in an ongoing play within the shadowbox, to potential flashpoint, a crisis with the building of the Wall in August, 1961 in a city which had a mountain built of its World War II bones and ruins, reaching fever pitch with the Cuban Missile Crisis, and remaining for the ensuing 27 years a symbolic thorn between East and West until the Wall came tumbling down, tumbling down.

From one perspective, starting with the Napoleonic Wars of 1803 through 1815 and continuing through the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, continuing then through World War I and the Revolution of 1917 in Russia, the entire conflictual history of central Europe may be seen on a continuum, with periods of hot and cold warfare interspersed by accords and treaties and uneasy armistice, only to be shredded into eruption again in one hot spot or another, right through to Kosovo and the conflicts among the former Yugoslavian states in the 1990’s.

Have the nations learned from the Cold War and, during it, from the history of the hot wars, tempered by the potential unforgiving brutality and absurdity conjured by the nuclear age, such that now they may say, with grave finality, over the corpses of the millions who perished before their time at the bad end of a bullet or bomb, that they have beaten their swords permanently to ploughshares? Only time may provide the answer.

We return momentarily to the Mallon piece of yesterday, remarking on Stalin’s "freedom and justice" May Day proclamation in Red Square. It hearkened of the same notions which eventuated in the reality of glasnost and perestroika of the final years of the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Yet, until 1985, it had never become a reality within the Soviet system.

And then, when it began to fuse with capitalist notions economically and democratic notions politically, the result of the inevitable motile inertia of the human soul toward the light of freedom in any land and in any time, four years later, the Wall was pushed to the ground by its former captives. The iron curtain soon thereafter ceased to be. It seemed then so simple, even anti-climactic: the peaceful push, the chipping away with hammers, without the interposition of machine guns or tanks to interrupt with blood the joyous celebration.

It took a new generation to realize a dream of freedom from the enslavement of dictators, starting with the czarist regimes of old Russia. Memories of cruel injustice die hard and live long, eventually must die out with generational time before dreams of the foresighted may be finally realized, often, maybe usually, through the cruelty of more injustice and more blood and more sacrifice laid to waste in the meantime.

It would be so, too, in America, through the inhuman cruelties of the nineteenth century into the manifold continuing injustices of the twentieth—all bent toward one premise: Empire, those writ in little and those writ in large.

And "Spectators", providing a glimpse of the Jungle Book attending the Empire building at hand in the various theaters of the Pacific, referring to the story from the previous day’s front page of the lifeboat of 12 selectmen having, at one point in their odyssey, to ward off a whale lest they become the latter-day analogue to Jonah, reminds us once again that therein may be the answer.

Riki-tiki-tivi...

The piece, incidentally, from the Czechoslovakian News Letter, re the student-led underground resistance which had received and carried out an order to blow up a German munitions train headed from Czech territory to supply troops on the Russian front, reminds us of a concluding scene from that novel to which we have previously referred you on occasion by our friend in the Caribbean, so because the means of explosion of the Nazi train were bombs made from fountain pens.

Moral: Never underestimate the ink with which to the table a good student of history might bring.

Ah, Juicy Fruit.

![]()

![]()